A Much Maligned Cellist: The True Story of Felix Salmond and the Elgar Cello Concerto (Part 3)

Tully Potter

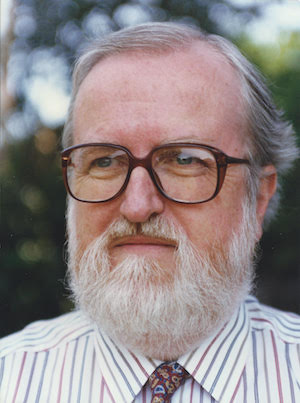

Original image provided by the Salmond Family.

This blog is a continuation of a multi-part series. Revisit Part 1 here, and Part 2 here.

The original article first appeared in the Elgar Society Journal.

The next development in the saga was that Fred Gaisberg of HMV wanted to record the Concerto—he had obviously not been put off by the première. As had happened with the Violin Concerto, just four 12-inch 78rpm sides would be available, but the more compact Cello Concerto would not need to be cut quite so drastically—the Scherzo would require only a small excision and the Adagio would be accommodated complete on one side. Sadly Salmond was under contract to Vocalion, so could not be considered. Guilhermina Suggia was approached but wanted too high a fee. The choice fell on the young Beatrice Harrison, who went with her sister Margaret to play the work to the composer and ended up being accompanied with inimitable brio by Elgar himself. In the session at Hayes on 22 December 1919 she did a reasonable job, setting down three movements successfully with Elgar conducting, but had to re-make the Adagio—the make-up session, originally scheduled for Elgar’s stint at the studios on 24 February 1920, did not take place until 16 November, almost a year after the first one.

SUCCESS IN MANCHESTER

Meanwhile Salmond, unabashed by the shenanigans over the première, gave the Concerto its second performance in Manchester on 20 March 1920, the Hallé Orchestra being conducted by none other than Coates! The cellist must have felt at least a pang of déja vù, as his second contribution to the concert, Bruch’s Kol Nidrei was followed by Scriabin’s Third Symphony, The Divine Poem, and the rest of the programme consisted of pieces by Wagner. Samuel Langford had this to say:

“Among works of its kind the ’cello Concerto of Elgar will rank high. There appears to have been some want of judgment about its first performance in London, but there was no mistake on Saturday. Mr Felix Salmond played most beautifully, with a polish and finish which set the lean and incisive technique of the work in the happiest light, and gave to the clear and serene beauties of its melodies the distinction and movement of some finely slender animal. For our own part we liked best of it all the idyllic song of its first movement. The whole plan of the work seems to be to give the sense of successive intermezzi rather than of substantial movements, but the miscellaneous matter of the closing movement gives the work in the end quite the normal duration.” (The Manchester Guardian, 22 March 1920)

In that era when North and South were like worlds unto themselves, this concert was not noticed by the metropolis-centric musicians of London; and when Beatrice Harrison was planning her rendering with sister Margaret, on the afternoon of 29 May at the Wigmore Hall, she advertised it as “second performance”—she was on safer ground in adding “first with piano.”

On 7 April 1920, Lady Elgar died of cancer in her husband’s arms. Carice and devoted friends did their best to solace Elgar but he was inconsolable. Alice was to be buried on 10 April in her preferred place, the hillside cemetery at St Wulstan’s Church, Little Malvern, and there was little time to prepare the funeral service. Frank Schuster and Carice asked W.H. Reed to bring some colleagues to play the Piacevole from the String Quartet, a favourite with Alice. Some sources claim that Salmond was involved but in his memoir of the composer, Reed states categorically that the other players were Sammons, Jeremy and B. Patterson Parker, a member of the LSO and the cellist of his own quartet (Reed, pp. 67).

No doubt Salmond was one of the many who sent expressions of sympathy. On 20 August 1920 he wrote to Elgar from Brighton, describing a happy encounter with the former Alice Stuart-Wortley, now Lady Stuart of Wortley and known to the composer as his muse ‘Windflower’:

We have been here since the 9th & are staying until Sept 6th. I am wondering how you are & whether your long stay at Brinkwells has done you good – I sincerely hope so. I spent a delightful afternoon, before leaving town, with Lady Stuart – We gave a brilliant performance of the Concerto! How splendidly she plays – since then I have had a complete rest from the ‘cello & I am sure it will do me good. The weather here has been wonderful, & the rest & thorough “laze” most enjoyable! I am looking forward so much to seeing you soon again & I only hope we may do the concerto together somewhere next season. My wife sends you her kindest regards – Please remember us to your daughter &, when you feel inclined, let us have a line to say how you are. Always affectionately

Your

Felix

His wish for a performance with Elgar in the next season was fulfilled at Birmingham on 10 November: the Concerto was framed by Falstaff and the Second Symphony in an all-Elgar programme with the Municipal Orchestra. Langford was again present:

“Mr Felix Salmond played the concerto, which now becomes quite a clear work of well-calculated effect, and is bound to become a favourite with every leading player. The nobility of the work as read by Elgar today hardly appears in the score to the casual eye, and its true interpretation will need to be promulgated.” (The Times, 11 November 1920)

Late in 1920 Salmond formed the Chamber Music Players, a piano quartet with William Murdoch, Albert Sammons and Lionel Tertis, and they gave their first concert at the Wigmore Hall on 6 January 1921. Within days the Salmonds’ second daughter Muriel was born and on 15 January Lillian Salmond wrote to Elgar:

Thank you very very much for the lovely gift you have sent to our little darling.

I can’t tell you how glad & proud I am that you are to be her Godfather. She is a very lucky little girl! I hope you will think she is sweet – Perhaps she may grow up to be very musical & then you may feel proud of her – I hope so.

Again best thanks. I am looking forward to seeing both you & your daughter tomorrow.

Sincerely yours

Lilian Salmond

On that very day, Beatrice Harrison played the Elgar Concerto at Queen’s Hall, with the composer conducting the regular orchestra of Sir Henry Wood—who took the rest of the programme. The critic of The Times, again almost certainly Colles, commented in the usual London-centric manner:

“There was no new work in the programme of the Queen’s Hall Orchestra on Saturday afternoon, but the revival of Elgar’s Violoncello Concerto, produced a year or so ago, and neglected since, was a matter of more importance than first performances often are. … a performance was secured which should produce some revision of opinion among those who werte disappointed by the first one. The violoncello concerto in E minor is not a work likely to create a sensation as the first symphony did, or one to arouse the ambitions of solo performers, as the violin concerto did. Probably violoncellists are right in saying that it does not ‘show off the instrument’, or challenge their technical powers in any conspicuous way. There are some passages which seem rather awkward for the instrument without being particularly effective. The greater part of the music moves, as it were, in a half-light; ideas are hinted at rather than fully expressed. The first three movements at any rate have more the character of a suite for violoncello and orchestra than of a concerto. Only the finale is developed at length. Yet the whole work is unmistakably Elgar from the first statement of the motto theme by the violoncello to the broad peroration which draws together the various threads in the finale. There is scarcely a phrase anywhere which one could imagine to be the work of anyone else. And in such an age of re-writing as the present one is, the power of any composer to be unflinchingly himself is too valuable a thing to be lightly passed over. Moreover, the violoncello concerto is certainly an advance on any of the previous symphonic works in its freedom from the tendency to labour the material with more or less vain repetition. If it is slight, it is quite frankly so; a whimsical fancy unifies its changing moods, and delicate touches of orchestration relieve the harmonic sentiment, and prevent it from cloying. Miss Harrison seemed to understand its character very well, and was able to keep the cantilena easily in the foreground, while the orchestral players showed themselves masters of the art of accompaniment. The work was sufficiently well received to make us hope that it will now take the place in the repertory which it certainly deserves.” (The Times, 17 January 1921)

This review, while expressing one or two opinions which we would not entertain today, is important because it marks a turning of the tide in the Concerto’s fortunes in London, and Harrison’s self-assurance as its interpreter. (Later that year she and Elgar gave it in the Three Choirs Festival at Hereford; and she also took it to Vienna.) On 27 January 1921 John Barbirolli, still known as Giovanni, essayed the Concerto in Bournemouth with the Municipal Orchestra conducted by Dan Godfrey. To his dying day, Barbirolli—in his youth yet another metropolis-fixated musician—was convinced that his had been the first out-of-town performance; but as we have seen, it was the third. On 14 March 1921 Salmond, now recognised as England’s premier concert cellist, played Brahms’s Double Concerto at Queen’s Hall with Sammons and the LSO under Coates; on the 23rd the unofficial Elgar quintet got together for a recital of all three chamber works, under the auspices of the London Chamber Concert Society; and on 16 June Salmond was the soloist in Strauss’s Don Quixote, with Hamilton Harty on the Queen’s Hall podium. But he had developed the notion that in the United States he would have even more of a career—and both he and Lillian apparently felt that their marriage, now in a sticky state, would fare better there, with the Atlantic between them and Adelaide.

The story concludes later this week in Part 4.

Works Cited

Reed, W.H. Elgar As I Knew Him. Victor Gollancz Ltd: London, 1936.

TULLY POTTER was born in Edinburgh in 1942 but spent his formative years in South Africa. He is interested in performance practice as revealed in historic recordings and has written for many international musical journals, notably The Strad. For 11 years he edited the quarterly magazine Classic Record Collector. His two-volume biography of Adolf Busch was published in 2010 and he is preparing a book on the great quartet ensembles.

TULLY POTTER was born in Edinburgh in 1942 but spent his formative years in South Africa. He is interested in performance practice as revealed in historic recordings and has written for many international musical journals, notably The Strad. For 11 years he edited the quarterly magazine Classic Record Collector. His two-volume biography of Adolf Busch was published in 2010 and he is preparing a book on the great quartet ensembles.

Subjects: Historical, Repertoire