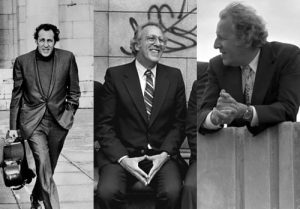

David Soyer, cellist and founding member of the Guarneri String Quartet, passed away on February 26, 2010—one day after his 86th birthday. Michael Tree, violist, and John Dalley and I, violinists, the other founding members, played in the quartet with Dave for almost forty years and we knew him for close to fifty. Peter Wiley, a former cello student of Dave’s and his successor in the Guarneri Quartet, has known him for easily forty years. Given the close musical and personal relationship that we had with Dave stretching over decades, it is hard to believe that he is no longer with us.

Dave and I first met at the Marlboro Music School—quite literally at a rehearsal for Brahms B Major Piano Trio. In the course of that two-hour rehearsal, I learned very quickly that Dave was smart, direct, even blunt, yet full of wit and charm. And from his very first notes, I knew that I was in the presence of not only an outstanding cellist and musician, but also someone with a distinctive and compelling voice. Dave’s playing could never be confused with that of a solid but generic cellist. As in everything about him, music included, Dave was an original.

At that rehearsal’s end, the pianist (who shall go un-named) told us that she had only learned the first movement of the Brahms Trio and would need at least a week or two to learn the rest. Dave immediately went to the scheduling office and cancelled the group. I had learned two more things about Dave: he would not tolerate people who were unprepared and he had not the slightest trouble speaking his mind.

People who knew Dave have occasionally asked me whether it wasn’t difficult working with him. Dave was even gruff at times, and highly opinionated to boot, but everything about him was up front. You knew what he thought and where you stood immediately. There was substantial comfort in this. Dave would fight for his musical ideas in quartet rehearsals, but once an issue had been decided whether in his favor or not, the subject was closed for him and without open animosity or hidden bad feelings.

Dave was also a most worthy traveling companion. In the countless taxis, trains, planes, and meals we shared on tour, you could depend on him for stimulating company. Dave was at home talking about a large range of things including politics, art, and history. Sometimes he would come up with strange facts out of the blue about, say, the sex life of earthworms or the Jovian moons of Jupiter. We would accuse Dave of making these things up but he wasn’t. Dave, a man who never had the benefit of an extended formal education, was very well read. Of course, we talked about music and musicians as well. At the end of a so-so meal in a so-so hotel far away from home, Dave would sometimes lean back in his chair and finish the conversation about the latest performance we had heard by saying in a vaguely Eastern European accent, “I rub stick against rope. Make money.”

Yes, Dave was entertaining and sometimes downright funny. Several years ago, the Guarneri Quartet received the Ford Honors, a yearly award presented jointly to an artist by the University of Michigan and the Ford Motor Company. Dave had already retired from the quartet but he came out to Ann Arbor, Michigan with the rest of us for the ceremony. As our elder statesman, we asked him to accept the award for the quartet. First, the University president spoke, then Ken Fischer, the concert series presenter, and finally, a Ford representative. When he had finished, the gentleman from Ford handed Dave a plaque with our names on it. Dave looked down at the plaque, then up at the audience, and said, “Actually, I expected a car.” When the laughter had subsided, Dave added, “In green.”

I last heard Dave perform in a Beethoven String Trio in Marlboro two summers ago. It was superb playing- not considering his advanced age- but simply superb for any age. He played with style, impeccable intonation, and perfect bow control. I congratulated Dave afterwards and asked how he could bring off such a performance considering that he was well into his eighties. Almost no string player continues performing at that age and those who do probably shouldn’t. Dave’s response: “Arnold, you’re getting old. You asked me the same thing after a performance last year and you’ve forgotten what I said, so I’ll have to tell you again. I’ve sold my soul to the devil.”

When someone I know dies, I find myself taking inventory almost without realizing it. What kind of a person was he? What did he mean to me and the other people who knew him? What lasting mark did he leave in the world? In Dave’s case, I will remember him as a marvelous cellist, uncommon musician, and as an extraordinary human being. I will remember Dave, whose bold and distinctive playing was a hallmark of our quartet’s music making; Dave, who threw his cello students out when their lessons were unprepared but who helped them find an apartment or saw to it that their living expenses were taken care of; Dave, whom my dog Flicka loved because against house rules he fed her bagels behind my back; Dave, who we will be telling stories about for the rest of our lives.

A couple of years back, Dave was asked on the radio what he’d like to come back to earth as in his next life. Knowing Dave as well as I do, I imagined him again as a musician, but also as an artist, a historian, a writer, an editor, even a collector of rare books. But I should have known better than to expect the expected when Dave was so full of the unexpected. Dave told the interviewer that he’d like to come back to earth as a tugboat captain.

As you know, Dave, my wife Dorothea and I live in an apartment that looks out on the Hudson River. We’ll be watching for you.