Happy New Year! I wish you all a happy and healthy 2019 – with great intonation and beautiful sounds on the cello!

Today’s adventure in Feuillard-land will continue with some more dotted rhythms, and then return to the sautillé and up-bow staccato strokes that were first addressed in No. 32.

Variations #27 and #28:

These two variations continue with the staccato dotted rhythms from last week, but this time with hooked bowings. As I mentioned in the past, I ask the students to play each variation completely in the lesson. In part this is for developing skills of concentration and relaxation. But also because every note on the cello has different properties and we are trying to make them all sound the same. There are no short-cuts in learning these principles, and our job as teachers is to be patient and provide a nurturing, supportive environment in which the students can develop their skills.

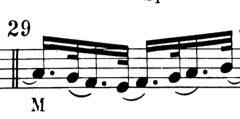

Variations #29 and #30:

For these variations I like to ask the students to play again with a “lilting” sound (like we did in Variations #19 and #20). That means releasing more and floating on the longer notes, and using a more gentle articulation. Iestyn had already used this stroke in the first movement of the Goltermann Concerto #4, and in the Dvorak Humoresque.

Variations #31 and #32:

These two variations work again on the sautillé stroke that was first encountered at the end of No. 32 (Variations #25 and #26). It has been several months since Iestyn worked on those variations, and he has clearly absorbed the main technical issues involved:

- using an active upper arm and a passive wrist

- finding the right part of the bow for the bounce at any given tempo

- getting the right contact point for a good sound

- letting the bow bounce by itself, and staying out of the way

- finding the right height of the bounce for evenness

- staying relaxed

- being able to coordinate vibrato with the stroke for a better sound

- getting the tempo to be faster

In this performance in the lesson Iestyn was able to get the tempo up to 75=quarter note, which is much faster than he had been able to play the sautillé variations in No. 32. As I mentioned to him when we worked on those earlier variations, our goal is to get to 80 in order to be able to play the Elgar Second Movement at the tempo indicated by the composer. With a little more time Iestyn will undoubtedly reach that tempo – and I look forward to hearing him play the Elgar in a few years!

Variation #32 is a bit more complicated for coordinating the left and right hands, and it is still a “work in progress” for Iestyn. Although the main beats are all down bows, the bowing direction reverses on the subdivided part of the beat because of the triplets. One has to be careful that the left hand is together with the right hand, and recognize that the subdivided part of the beat is on an upbow. It is good to slow it down and stop on those upbows until they are ingrained in the body. It is also sometimes helpful to feel the upper arm moving “in” and “out” for those subdivisions. I recommend practicing this with the left hand leading; and then with the right hand leading. It feels different to us when one hand or the other is “leading” – and we have to figure out which one results in a better performance. This Variation was still a “work-in-progress” for Iestyn.

Variation #33:

This is the final variation in No. 33, and it works again on the issues first seen in No. 32 (Variations #22-24): the up-bow or down-bow staccato (or “hooked staccato” or “slurred staccato”) However instead of repeating the same notes with the staccato stroke, this time the variation requires more coordination between the left and right hands. Once again Feuillard first presents a concept in a “simple” version, and then adds complexity later. Iestyn has absorbed the basic technical issues from his experience with the earlier variations, and he played it well in his first attempt.

I reminded Iestyn about the Heifetz “Hora Staccato”, and suggested that he listens again to the Locatelli sonata for “inspiration” about this stroke. I also suggested that he should continue to work on both the sautillé and staccato strokes so that when he approaches pieces such as the Tchaikovsky Rococo Variations he will have the tools needed to be able to play them.

I would like to thank Iestyn for being the “guinea pig” in all the videos of Feuillard No. 33. He has made great progress in his bow technique.

With the New Year, next week’s blog will begin the critically important work on string crossings, with the Feuillard No. 34. We will examine the different parts of the arm that can do these vertical motions, and analyze the four bowing figures that are the basis for all string crossings. My pre-college student Tristan will be featured in the videos as he begins his work on these variations.

*If you have questions or comments about The Joy of Feuillard, Dr. Robert Jesselson can be reached directly at rjesselson@mozart.sc.edu.