Running After What is Behind You

Selma Gokcen

Much of our training as cellists has us working long hours, working hard, but are we working smart? Do we know what is productive and what is counter-productive in our manner of working? How do we know? Is it possible to know?

Many years after my cello study at the Juilliard School, I hit a wall. I could not go further in my work with the traditional methods of cello technique, cello etudes, additional lessons and hours of practice. It seemed I was going round in a circle. I finally realised that solution to problems at the instrument might lie somewhere beyond the green pastures I had hitherto spent my life exploring. I said to myself: Maybe the study of music is like science. You have to go into the Unknown to find the answers.

So I began reading far outside of music: sports psychology, the science of consciousness, accelerated learning literature, until I stumbled across the Alexander Technique. In Alexander’s own books, he speaks about his struggles to understand the psycho-physical nature of habit. Psycho-physical was his term for what we call today the mind-body connection. A century ago he already knew that there is no such thing as a purely physical manifestation in human movement. The mind informs every gesture and there is a capacity for becoming aware of our movement at a completely new level.

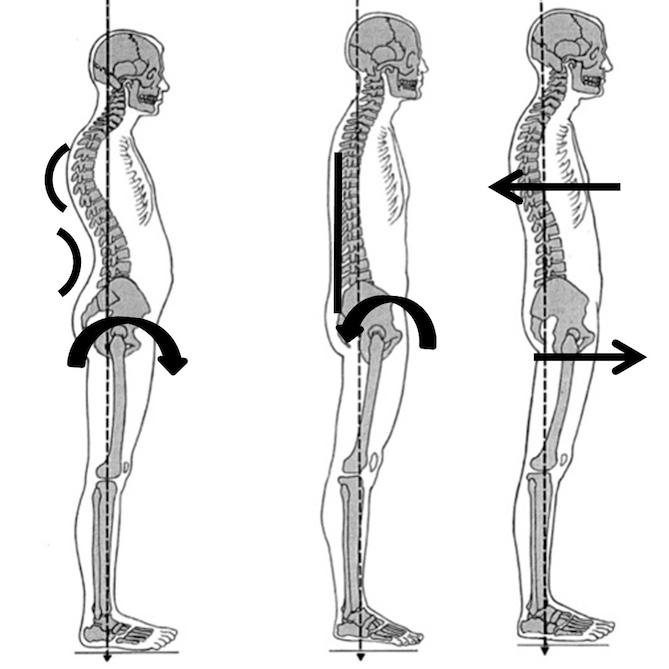

Our conservatoire training is based on models dating back to the 18th century. Musicians were rigorously trained in the craft of playing an instrument as well as the art of making music, and the candidates would have been selected from a populace who lived close to Nature. Life was active in a way we cannot imagine. People walked several miles a day or rode on horseback on a regular basis and thought nothing of it. I collect pictures of musicians in both traditional societies and from centuries past. One thing they share in common…they are embodied. What does this mean? From the way they wear their heads to the upright state of their backs and spines and their feet planted on the ground, one sees the same presence and attention as one can see in the natural animal (not the domesticated one!) The eyes are gazing from a quiet within, the body is poised and ready to move. The natural was once the norm.

In 200 years, modern life has given us many benefits but it has also corrupted our connection to Nature, particularly if we live in cities. Today’s music student is likely to have grown up spending many hours in front of television, computers and video games as well as riding around in cars and buses. Sitting and looking at screens is the modern affliction. The harmful effect on our sensory awareness, on our proprioceptive sense (the feedback we get from movement and body position) is incalculable. The first generation to live mostly from the neck up is here, and of course virtual reality is a delight for such people. Who needs a body?

Artists do, musicians do. The rhythm of music is in the body first. The arc of a phrase lies in the natural curve of a movement. Embodied musicians make music on an entirely different level, one which speaks to the oldest and deepest part of our consciousness. The Alexander Technique re-awakens the rhythms of the body, its sense of movement, and its fundamental ability to coordinate itself. We can move as beautifully and gracefully as animals and enjoy the sense of our movement, but even more important, we can become conscious of how our ‘thinking in activity’ can work for or against us.

So that brings me back to the first question…Do we know what is productive and what is counter-productive in our manner of working? By becoming aware of the principles of good coordination (and the accompanying quality of attention), we have a standard of measurement in our daily work. We can learn to recognise psycho-physical habits which interfere with these principles and which are therefore counter-productive.

In the meantime, get to know some of your habits at the cello…the worst ones can become your best friends, in that they will offer the richest material for work on yourself. Next column: learning to read the signs.

Subjects: Playing Healthy

Tags: Alexander Technique, artistry, artists, back, balance, body awareness, Coordination, gestures, Gokcen, Habits, head, nature, productive, Selma, sensory awareness, Spine, sports, training