Author: Robert Battey

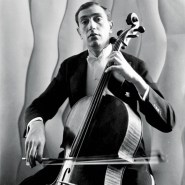

Robert Battey is a DC-area cellist, teacher, writer, and clinician.

His principal teachers were Bernard Greenhouse and Janos Starker, and he holds performance degrees from the Cleveland Institute of Music and S.U.N.Y.-Stony Brook. Bob’s career has included stints in professional string quartets and symphony orchestras, as well as many recitals and concerto appearances throughout North America, including several Bach Suite cycles in a single concert.

He has served on the faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City, S.U.N.Y.-Potsdam, and the Levine School in Washington. He is Music Director of the Gettysburg Chamber Music Workshop and teaches at Cellospeak. He was also a founding faculty member of the Bach Cello Suites Workshop. He has contributed two Cellochats here.

Bob specializes in working with adult amateurs, and his widely-used text, “500 Sight-Reading Exercises For Cello” is dedicated to that demographic. He is currently preparing a wholly new edition of the Popper etudes.

A prolific writer, Bob’s articles and reviews have appeared in the Washington Post, in STRINGS magazine, the arts blog "A Beast In A Jungle," and in various ASTA newsletters.

By Robert Battey March 16, 2022

By Robert Battey January 20, 2021

Subjects Historical

By Robert Battey December 14, 2017

Subjects Artistic Vision, News

Tags

By Robert Battey April 24, 2015

By Robert Battey December 15, 2013

Subjects Practicing

Tags accents, alignment, Awareness, Bach, Bach Cello Suites, bar lines, Battey, Beethoven’s “Archduke” Trio, Brahms Double Concerto, Capucon, cello, cellobello, communication, complexity, conservatory, counting, dissonance, Feuermann, focused listening, great artists, great composers, intelligent artist, interpreter, interpretive decisions, intonation, melody, metrical organization, musical critic, musical phrasing, performer, phrase lengths, phrasing, powerful, recordings, resolution, robert, Rostropovich, score-study, slurs, studying, stunning effect, stylistic conventions, text, vibrato, Washington Post, Yo-Yo Ma, youtube

By Robert Battey September 8, 2013

Subjects Repertoire

Tags Achilles’ heel, alterations, Battey, cello, charming, composer, compositions, creativity, difficulty, effects, experimenting with rosin, flawed works, glissando, gummed-up fingers, increased tension, Leopold Auer, lyrical, master, melody, modern artists, musical transitions, opening material, options, Pezzo Capriccioso, Piatigorsky, recordings, repeated notes, robert, Rococo Variations, rosin, Rostropovich, sections, sections of music, show piece, sticky problem with shifting, Tchaikovsky, transitions, trill, virtuoso

By Robert Battey January 16, 2013

Subjects Repertoire

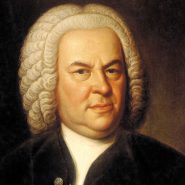

Tags accuracy, ambiguity, Anna Magdalena, Anner Bylsma, artistic, autograph, Bach, Bach Cello Suites, Bach Suites, Bach's original intentions, Bach’s precise intentions, Barenreiter, Battey, careless, cello, cellobello, challenges, colors, complexities, conclusions, curiosity, dilemma, Editions, editors, enjoyment, experimentation, flawed, genius, historical, inconsistent copies, instrument control, Instruments, interpretive creativity, interpretive ideas, Janos Starker, judgment, liberation, lute, lute arrangement, meaningful interpretations, monochromatic, normal teaching model, Pablo Casals, painting, parameters, paris, personal research, personality, phrasing, Pierre Fournier, printing, publications, rainbows, recordings, repertoire, response, Rhythm, robert, sloppy, slurs, study, Teaching, text booklet, textual, The Fencing Master, transcribing, uncertainties, virtuosity

By Robert Battey January 7, 2013

Subjects Artistic Vision

Tags Battey, Beethoven, commitment, critic, expertise, Heifetz, patience, Philosophy, problems, robert, Strings Magazine, traveling

By Robert Battey February 3, 2012

Subjects Practicing

Tags Accomplishment, Battey, cello, cellobello, character, Coordination, Development, dynamics, Effective, ensemble, harmony, Janos, Listening, music, perfection, Rhythm, sight-reading, Starker, success, Technique

By Robert Battey January 1, 2012

Subjects Practicing

Tags ability, Battey, cello, cellobello, chamber music, ensemble, Observation, Practice, Rhythm, robert, sight-reading, success, Technique, virtuoso

By Robert Battey December 1, 2011

Subjects Practicing

Tags art, Battey, cello, cellobello, chamber music, coaching, conservatory, Development, discipline, ensemble, frustration, goals, music, music-making, robert, sight-reading, students, Teaching, Technique, workshops