Practicing, Some Practice Advice (Part 1)

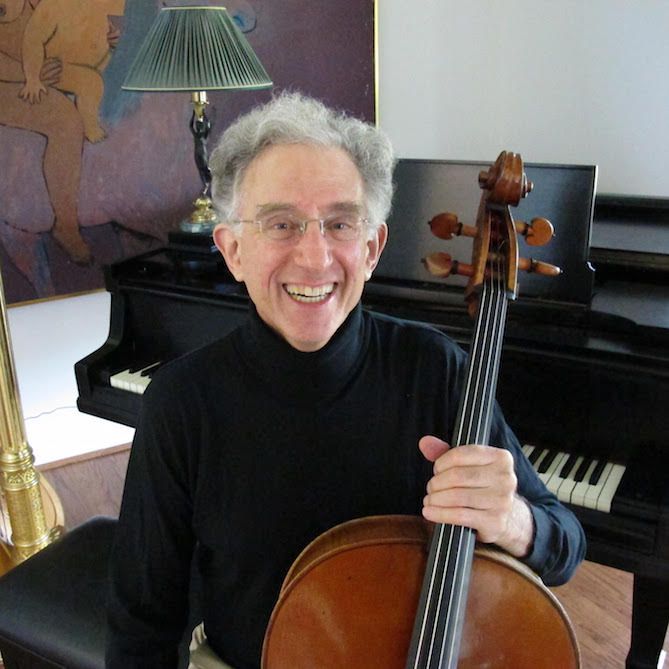

Michael Haber

I’ve written this brief essay for purely selfish reasons: I like to see my students improve. When they do, I feel happy, they feel happy, I go home for dinner a happy man.

What follows is intended to help you organize your practicing, and your thinking about your practicing, in an effective way. Your progress, mine too, depends on the quality and quantity of this work. It’s also intended to encourage you to practice, period. Not all of my students are always inclined to work as well and as much as they should.

I should confess from the beginning that I have always loved practicing. It is the royal road to instrumental mastery and the incomparable satisfaction of playing music as well as it deserves to be played. I have looked forward to opening the cello case daily, always with the hope that the day’s work would move me closer to becoming a good musician.

For me, playing the cello is a personal and very individual spiritual act….with physical consequences. I think, feel, dream, imagine, therefore I make a sound. While I of course need my body and hands to play the instrument, when things are going well I feel like I’m playing the cello with my mind—or if you prefer, my soul—that I could just as well be singing, but that I happen to have a cello in my hands, so the sound emerges that way. Many years ago a cello colleague said to me, “You play because you think.” I replied, “No, I play because I love.”

Your feeling for the music you love and wish to play is also a very personal area and an almost impossible one to write about convincingly anyway. What I’ve written is intended to help you develop the physical means and skills to turn your own understanding of music, through the cello, into sound and into the way you wish it to sound.

Goals, Basic Principles of Practicing, How I Practice, What I Practice: Technical Work

Setting goals is the first step in organizing one’s work.

Making music, with understanding, imagination, conviction and skill, is the goal. The cello, like any other musical instrument, has been created for this purpose alone. Beautiful as cellos and bows can be to look at and possess, they are tools and voices for the soul and the imagination. This is never to be forgotten.

This goal will remain out of reach until you can use the cello with freedom, confidence and a high level of skill and accuracy—until, said another way, you have mastered the “technique” of playing the cello. A significant part of one’s practice time should be devoted to acquiring this mastery.

Here is a list of many aspects of this “mastery” I work on, daily.

- First and foremost, accurate intonation in all registers of the cello.

- A pure, deep, resonant and unforced tone, in all registers, all dynamics, all bow strokes.

- A command of the bow so that the variety of articulations, colors, nuances and dynamics I can produce is unlimited.

- A vibrato, which does not distort the pitch of the note being vibrated and which is capable of a wide range of intensities and colors.

- The ability to play with equal ease in lyrical and virtuosic passages and compositions.

- A compelling and distinctive musical personality, which brings together the qualities already listed into an artistically satisfying whole.

Some Basic Principles of Practicing

Goals, at least as I see them, have been set. Now we need an equally clear idea of how to achieve them with as little wasted time and effort as possible. In other words, we need to know how to practice and what to practice.

Here are the three general principles on which my own practicing is based:

- In a given period of time, organized work—by which I mean practice sessions structured to accomplish clearly identified short and long-term goals—accomplishes more than disorganized work.

- If one works on a desired skill with enough patience and determination and doesn’t give up easily, one will progress toward acquiring that skill.

- Working every day on the complete range of technical skills on which excellent cello playing depends—in small amounts, without straining—will, over time, move the general level of one’s playing higher, leaving no essential skills neglected or undeveloped.

How I Practice

While this is obviously more easily demonstrated in a lesson than written about, I can say a few things about how I work.

- I practice very slowly, slowly enough so that my mind can stay ahead of my fingers. I do not try to play things quickly until I have mastered them slowly, unless it is to try out a set of fingerings and bowings to see if they will work at a faster tempo.

- If I can use a mixed metaphor, I listen to myself like a hawk, with a friendly but mercilessly critical attitude, constantly comparing what I hear coming out of the cello with what I would like to hear and working to reduce the discrepancy between the two.

- I take a very practical, experimental approach toward finding solutions to both technical and musical challenges. I try every idea I can think of, bowings, fingerings, colors, phrasings, until I get closer to the results I want. By “results” I mean the specific character, intonation, articulation or phrasing for which I’m looking.

So…when I work, I do so in a general atmosphere of intense mental concentration, listening for every flaw in my playing, experimenting to find solutions to problems, constantly working to get closer to the way I want to sound.

One could say that practicing is the process by which one works to make one’s ears happy.

What I Practice: Technical Work

The cello remains a frustrating set of obstacles without the establishing and constant reestablishing of a good technique. Part of my daily practice is spent on building and strengthening my technical command of the instrument, something I can never take for granted.

I do all the traditional work, proven effective for many generations, which serious string players have always done, namely:

- Four octave scales in a variety of bowings and fingerings, major and minor; scales in thirds, sixths, octaves, and arpeggios.

- Finger and trill exercises in all registers of the cello, primarily from János Starker’s An Organized Method of String Playing.

- Exercises to develop vibrato, tone production, shifting, special bow strokes and string changes, articulation etc.

- Etudes, from collections by Duport, Lee, Franchomme, Popper, Servais, Piatti and others, selected to help with the development of specific skills, such as security and accuracy in thumb position, octaves, etc.

- Virtuoso short pieces, to build confidence and competence in fast playing.

Athletes don’t do push-ups just to do push-ups, we too do our “exercises” as a means to a larger goal. As an athlete needs a good coach, one of my roles is to help you select what and how much of the above to do so that you do not strain and hurt yourself, as in fact many musicians do. So, please, especially if you have not done this kind of work regularly, don’t begin doing large amounts of these activities, all of which, like any exercise, can be harmful if done improperly or excessively. We need to figure out, together, what is appropriate for you as an individual.

I recall when I studied with Mr. Starker, he said to never spend more than 15 minutes a day on finger exercises, his or anyone else’s.

As a general rule, the above materials should take up about one half of your practice time.

I think it’s a good idea to be working on a concerto, a sonata or other major work with piano, a Bach Suite or other unaccompanied work, and a short piece. Work on a virtuoso short piece can be included in the period of technical work.

How much should you practice? Ivan Galamian suggested in his chapter On Practicing, in his Principles of Violin Playing, that 4 hours was adequate. When I was a student, I worked in the morning and in the evening, afternoons usually being occupied with classes and rehearsals.

Hear Mr. Haber live in performance with the Gabrielli Trio:

Cellist Michael Haber graduated with high academic honors from Brandeis University with a degree in European History. He did his graduate work at Harvard and at Indiana University. His principal cello teachers were János Starker, Mihaly Virizlay and Gregor Piatigorsky.

Cellist Michael Haber graduated with high academic honors from Brandeis University with a degree in European History. He did his graduate work at Harvard and at Indiana University. His principal cello teachers were János Starker, Mihaly Virizlay and Gregor Piatigorsky.

Mr. Haber was a member of the Cleveland Orchestra under George Szell and the Casals Festival Orchestra under Pablo Casals. With the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, he toured and recorded throughout Europe, the USA and Asia. He was the cellist of the Composers Quartet, in residence at Columbia University in New York City, and of the Gabrielli Trio.

Among the schools and festivals where he has been on the cello and chamber music faculties are Oberlin College, Indiana University, the New England Conservatory of Music, the Eastman School of Music, Boston University, the University of Akron, Aspen, Marlboro, Yellowbarn, Aria and the Manchester Festival. For 10 years he was the coach for the cello section of the New World Symphony in Miami Beach and has presented masterclasses at universities throughout the USA, and in Australia, New Zealand, Egypt, Turkey and Switzerland.

Among the comments for Mr. Haber’s performances, the New York Times spoke of “the lyricism and perfection of his playing.” The London Times called him “ a romantic cellist “ and The Cleveland Plain Dealer called him “ a superb musician.”

Subjects: Practicing

Tags: Duport, Gallamian, intonation, Janos, Michael Haber, Piatti, Popper, Practice, scales, setting goals, Starker, Starker method, technical work, Technique, trills