Practicing, Some Practice Advice (Part 2)

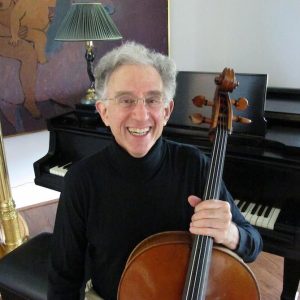

Michael Haber

Frustration and Discouragement, Orchestra Auditions, Some Final Thoughts, a Final Comment

FRUSTRATION AND DISCOURAGEMENT:

Now is the time to talk about our number one enemy.

When I look back over all my teaching, one observation stands out above all others. It has not been a lack of talent or intelligence which stood in the way of progress for most students. It has rather been the fact that many people become both frustrated and discouraged by the amount of work and the unwavering discipline and persistence it usually takes to become an excellent musician.

I have something simple to say on this subject: frustration and discouragement have been the common lot of most of the musicians I’ve known, born of the eternal gap between our dreams of how we want to sound and make music and the reality of how we actually do sound.

Persistence, continuing to work, to look for keys to seemingly locked doors standing in one’s way, turns out to be the crucial element in whether an individual moves forward or not. And this forward movement is often, as the saying has it, two steps forward, and one step backward.

In summer time, when the heat rises, I dream of cool weather. The discrepancy between my fantasy of comfort and the insufferable heat makes me miserable. As soon as I accept the heat and stop tormenting myself with visions of snowstorms and cool breezes, I feel better and adjust to summer.

If you will accept that, for most of us, growth as a musician is a steep and long hill to climb, you will have a much easier time of it. Just keep putting one foot in front of the other: the view from higher up is worth it.

In effect, what I’ve written is, that’s just the way it is. Either one persists in pursuing something one deeply desires, through good times and bad, or one gives up. While this may not seem very helpful, at least I think it is truthful.

I vividly remember an incident from my own student days, which illustrates this beautifully. One of Josef Gingold’s violin students, a friend of mine, had broken up with his girlfriend and was in a miserable condition, too unhappy to work. As we stood talking with Gingold, my most admired and beloved teacher, I still remember his final remark: “I too was young, but I didn’t stop practicing.”

ORCHESTRA AUDITIONS:

Almost every cellist will spend part of their professional career playing in an orchestra. Even many of the great solo cellists (Starker, Rose, Piatigorsky, Rostropovich, Tortelier and Harrell come to mind), before they began their solo careers, were principal cellists of major symphony orchestras.

Everyone knows, or should know, that getting an orchestra job is a tough, competitive challenge. And taking an orchestra audition, to put it mildly, is an unpleasant experience for most people. It therefore makes sense to learn the standard orchestral excerpts far in advance of any attempt to audition for a job. Many of these excerpts are very difficult. All of them must be learned with the same meticulous attention to detail and musicianship which we bring to our other work.

I think one should begin learning this material during one’s undergraduate years rather than making a heroic attempt, four weeks before an audition, to learn twenty excerpts, some of which, like the Bartered Bride Overture of Smetana, are totally unforgiving to those who have not learned them well.

Some tips:

- Sometimes a student says to me, I’m going to this audition ” just for the experience.” Playing badly in front of a conductor or audition committee is not a valuable experience. Don’t go to an audition unless you are well prepared and can play all the required material at the level you think is necessary to get the job.

- Know the composition from which the excerpt is taken: it is very easy to tell whether the person auditioning is playing the excerpt without knowing how it fits into the piece as a whole.

- Don’t try to play like an entire cello section, especially when you see forte or fortissimo on the page. Scale your playing to have a convincing range of dynamics but never force.

SOME FINAL THOUGHTS:

One last idea, a conception, which can profoundly affect everything we do with, the cello, followed by a final comment.

All of us use our bodies, every day, with unconscious ease and grace, making thousands of perfectly coordinated movements. We think of something, we do it: the idea of the action generates the entire sequence of movements necessary to accomplish it.

For instance, you want to wave goodbye to someone. You don’t send a complicated series of commands to your back, shoulder, arm, etc. The thought of waving good-by generates all the required movements to do so and you wave in the most natural way, all your limbs and joints moving freely and easily, until the gesture is completed and your arm is by your side again.

This is what Kato Havas means by ” instinctive, organic motion.” We all move this way, every day, all day long, without thinking about it. This is the kind of motion on which cello-playing movements should be based, motion which comes from a central and complete conception in the brain of the action to be taken which allows us to move with complete freedom and ease, from the beginning gesture to the final one.

We all know from experience how impossible it is to play the cello with stiff, cramped motions, with tight, uncomfortable hands. It feels bad, it sounds bad.

While playing the cello will of course never be as simple as waving your hand, all of the instrumental solutions you search for should be based on your inner model of physical comfort and ease, on the way you have used your body your entire life. The closer you come to approximating your normal way of using your body when you play, the more “natural” your playing will be and the more comfortable you will feel.

Eventually, as the thought of waving goodbye was enough to give birth to the action, musical ideas will lead, in the most natural way, to the series of cello-playing movements and gestures necessary to turn these ideas into sound.

And a final comment.

Most of the musicians I’ve known have been intense, emotional types, which is just how I think it should be. Depth of feeling is the core of our art: without it, all other accomplishments lose their meaning.

It isn’t always easy, given our customary temperament, to work in a clear-headed, well-organized way, and I, as much as anyone, have struggled with that too.

I just want to say that getting your hands on the reins of your own soul, having the sense inside yourself of acquiring mastery over yourself, your instrument and your musical imagination will, in the long run, make you more free to make music, not less.

That is the underlying message of what I’ve written.

Hear Mr. Haber in performance with the Gabrielli Trio:

Cellist Michael Haber graduated with high academic honors from Brandeis University with a degree in European History. He did his graduate work at Harvard and at Indiana University. His principal cello teachers were János Starker, Mihaly Virizlay and Gregor Piatigorsky.

Cellist Michael Haber graduated with high academic honors from Brandeis University with a degree in European History. He did his graduate work at Harvard and at Indiana University. His principal cello teachers were János Starker, Mihaly Virizlay and Gregor Piatigorsky.

Mr. Haber was a member of the Cleveland Orchestra under George Szell and the Casals Festival Orchestra under Pablo Casals. With the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, he toured and recorded throughout Europe, the USA and Asia. He was the cellist of the Composers Quartet, in residence at Columbia University in New York City, and of the Gabrielli Trio.

Among the schools and festivals where he has been on the cello and chamber music faculties are Oberlin College, Indiana University, the New England Conservatory of Music, the Eastman School of Music, Boston University, the University of Akron, Aspen, Marlboro, Yellowbarn, Aria and the Manchester Festival. For 10 years he was the coach for the cello section of the New World Symphony in Miami Beach and has presented masterclasses at universities throughout the USA, and in Australia, New Zealand, Egypt, Turkey and Switzerland.

Among the comments for Mr. Haber’s performances, the New York Times spoke of “the lyricism and perfection of his playing.” The London Times called him “ a romantic cellist “ and The Cleveland Plain Dealer called him “ a superb musician.”

Subjects: Practicing

Tags: Auditions, Coordination, Experience, frustration, Michael Haber, personality, self, soul