The Forgotten Live Video Recording: Du Pré & the Dvořák Cello Concerto, 1968

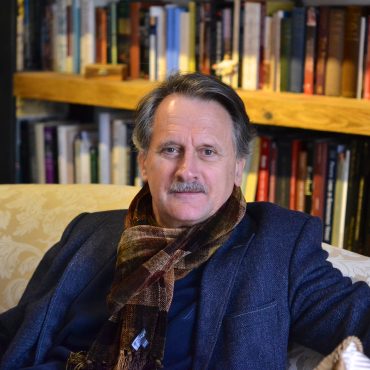

Tony Woodcock

The most wonderful video performance of the Dvořák Cello Concerto by Jacqueline Du Pré and Daniel Barenboim was added to YouTube just a few weeks ago. In this CelloBello exclusive blog is a moving, personal description by a young London musician, Tony Woodcock, who was 17 years old at the time. Below he recounts the unexpected political backdrop for this historic concert, which was hastily arranged in response to the 1968 Russian invasion of Dvořák’s home country of Czechoslovakia.

Tony Woodcock, by the way, grew up to eventually become the President of the New England Conservatory of Music, and was a primary supporter of the founding of CelloBello.com. My heartfelt thanks to him for his role in making our website possible, and for illuminating us on an extraordinary history that should not be lost.

—Paul Katz

It is a story that really begins 30 years before this astonishing performance of the Dvořák. We are in 1938, one year before the start of the Second World War and the West, led by Great Britain, sacrifices the country of Czechoslovakia to assuage the mighty expansionist ambitions of Germany’s Third Reich and its leader, Adolf Hitler. Britain’s Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in justifying the betrayal calls it “a country we know nothing about in a distant part of the world.” As a direct result the country is overrun and then occupied by the Nazis until 1945 when it is “liberated” by the Soviet Army becoming de facto part of the new eastern empire of the totalitarian Soviet regime. I have friends who lived through this time and they speak of the absolute misery perpetuated by the Soviets with fear and repression. “Our world was a perpetually grey and lifeless.” Then in January 1968 the First Secretary of the Czechoslovakian Communist Party, Alexander Dubček, started to liberalize and democratize the country, with something that was called the Prague Spring. Suddenly the country opened like a flower with color and joy and people started to feel how good life can be with their freedoms promoted and protected. But the Soviet authorities, which saw these freedoms as an attempt to break away from their empire, were watching all this very carefully.

In August 1968 the west was monitoring the combined forces of the Soviets and the Warsaw Pact countries as they massed on the border of Czechoslovakia. Then of August 21 some 500,000 troops and tanks invaded the country, arrested the political leaders including Dubček, and occupied the capital. The epicenter of protest and dissent was Wenceslas Square in the heart of Prague, the same good king we sing about in the Christmas carol. Just as in 1938 the west turned its gaze away from the tragedy and the country was again subsumed into the darkness of the Soviet Empire. But on that day, August 21, the Soviets had forgotten that they had an orchestra on tour in the UK, the Moscow Philharmonic with conductor Svetlanov and the great cellist Rostropovich as the soloist. And on that very night they were scheduled to give a concert as part of the BBC Proms at the Royal Albert Hall. The concerto was to be the Dvořák.

I was at this performance as a very young 17 year old musician, excited by the events seeming to swirl around me. To say that I had never experienced anything like it is a complete understatement. The Hall was packed and I was in the standing area just in front of the stage. The atmosphere was prickly with the electricity of the political events that were still unraveling that day. Then of course there were the protestors who you can hear giving vent to their feelings in the recording of the concert available on YouTube. The musicians played as true professionals through the din and tumult, although there was complete silence during the Dvořák. Rostropovich was magnificent.

Five days later there was another performance of the Dvořák Concerto. It had been put together quickly by Daniel Barenboim and the London Symphony Orchestra to raise relief funds for the Czech people, and the concerto was to feature his new wife, Jacqueline Du Pré. It was also given at the Royal Albert Hall but during the day because of the BBC Prom that night. In the late 1960s there was an astonishing confluence of young musical gods who seemed to take the entire world by storm: Barenboim, Zubin Mehta (just appointed Music Director of the LA Phil aged 28), Pinchas Zukerman and Perlman. But the most exciting and the most astonishing of this godly pantheon was undoubtedly Jacqueline Du Pré. Her personality, her ability to astonish and move an audience and her sheer engagement with music were on a different plane. She was, albeit for a brief time, the greatest cellist in the world, someone that Rostropovich described as “the only cellist that could equal and overtake my own playing.”

So the audience gathered at the RAH in vast numbers drawn by the political cause and the musical promise of something truly remarkable. No protestors this time. And in this recording, which was lost until very recently, we have all that and much more. Du Pré, at age 23, is at the height of her powers, finding nuances and colors in the concerto that no one had discovered before or since. She commands the audience in the hall and now, 50 years later in black and white and with a less than perfect audio, she commands us, looking back through history at this extraordinary event. At the end of this recording I confess I cast a tear. Then I watched the tribute to her made by Allegro Films for the BBC and there were more tears. I never knew Du Pré. I never worked with her. It was just her playing that I came to know and love. Perhaps I am being too romantic in my feelings and imposing upon her and the performance qualities and attributes that are more about me than the music. But I have listened to this performance more than once and my feelings seem real. This is a moment in musical history that has been rediscovered, like a major archeological find, reminding us of a genius who could and still does, inspire us with music that comes to us straight from her soul, her Deep Song.

Tony Woodcock is a leading pioneer in the field of arts management and music education. At the heart of his work is a dedication to positioning future generations of artists as independent innovators and community leaders. Tony was President of New England Conservatory from 2007-2015, following a transcontinental career managing orchestras including Minneapolis, Oregon, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic and Bournemouth Symphony. A veteran fundraiser, negotiator and institutional reformer, he has made dynamism and fresh ideas the foundation of his leadership, and has left a legacy of potent innovations still in evidence across the United States and Great Britain. As an orchestral CEO, he organized numerous international tours between Europe and the United States, successfully negotiated collective bargaining agreements with four major orchestras, and collaborated with a diverse array of celebrity talent, from Paul McCartney to Yakov Kreizberg. All of this was achieved against a backdrop of increases in audience and revenue. Tony studied music at Cardiff University, where he was recently awarded an Honorary Fellowship. He is now Visiting Professor for Social Entrepreneurship at Berklee Valencia and Visiting Professor for Entrepreneurship at the Reina Sofia School of Music Madrid, dividing his time between southern Europe and NYC, teaching, writing, and consulting on projects. You can discover more about his work on his website: scolopaxarts.com.

Subjects: Artists