Understanding Teachers (Part 2)

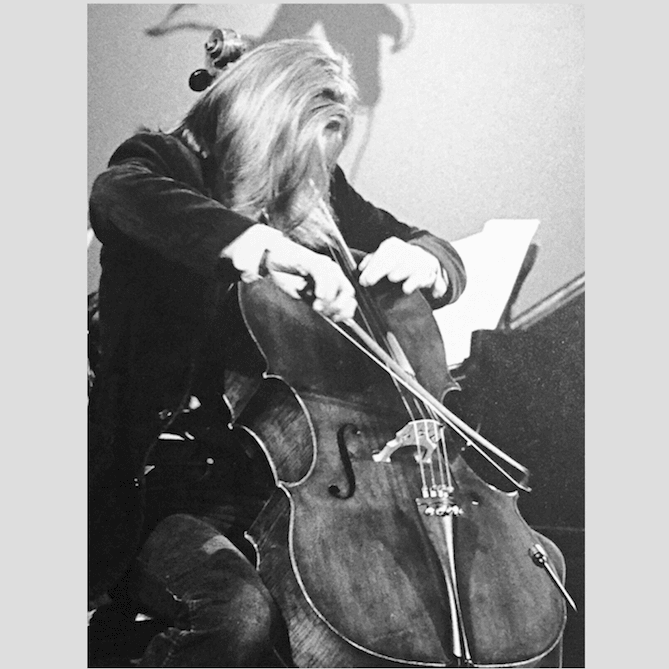

Anssi Karttunen

Jackie and “Hansen”

Very often people ask me to talk about my studies with Jacqueline de Pré but for years I desperately tried to avoid the subject, it was almost impossibly painful for me to talk about her. I used to think this was a personal problem of mine. Over the years, meeting other cellists who studied with her, I’ve understood that we had all had very similar difficulties talking about her. We all studied with her after she had already had to stop playing. When I met her, at 18, I knew her playing only through recordings. I was full of admiration for her but not at all prepared to the shattering experience it was to get to know her. It would take years to sort out myself from the turmoil of the very strong impression that she left in me. I now understand that I was very, very lucky to have met her, even if it certainly was one of the most challenging relationships an 18-year-old could get into.

One of the first problems all her students had to confront was that she had of course never had the time to think of becoming a teacher nor to intellectualise her ideas on music. What she did with us was not really teaching at all, it was more like a last desperate attempt to make music, not playing herself, but through the students.

The fact that playing through students was the only way of making music left for her made the situation almost unbearably complicated to deal with for a inexperienced person like myself. The tragedy she was living and the compassion one felt for her didn’t make things easier. Playing in front of her, trying desperately to play just like her and failing miserably I felt more and more at a dead end. After maybe ten-fifteen lessons I had to ask her if I could go on visiting her, but without the cello.

So strong was her influence that for years, even when I consciously tried to play not like her, I would be suddenly reminded of a comment of hers about a detail she would just love to have heard. Wanting to not play like someone is of course almost as clear a sign of dependence as trying to copy that person. A few years ago, when I finally managed to get through the slow movement of the Schumann concerto without thinking of her I knew I had learned my lesson.

I now know that meeting her was priceless in understanding how one can’t let one’s admiration for another human being become a burden by trying to copy. I might have never learned this had I not come in contact with the lovable volcano that was Jacqueline du Pré.

The legacy of Jacqueline du Pré is in the uniqueness of her talent. The instrument, the technique or the particular piece she was playing is not the point. The point is that she told a story of her life with every note she played on the cello and laid it all out in front of us in total sincerity. There are only a few artists every century for whom everything around becomes material for their own story. Music and the cello were the perfect and only ways of expressing her true self.

Recordings and videos are naturally how the world gets to know her today. They offer small windows to what her playing was like during a career which lasted barely 10 years, but they have also frozen her in time. She went through her whole career so fast that I wouldn’t even begin to judge any of her recordings as final statements, rather as part of a developing artist’s search for herself. After all, when she played her very last concert she was only just 28. No-one can know how she would have developed had she been able to continue playing.

The cello as a way of expression was how her personality could speak to the world. Although she played on several famous instruments, I don’t think one should read much into whether it was this or that instrument that suited her best. If anyone, she was able to transcend such earthly matters as instrument, bow and technique.

I got a good idea of how it was to play on her instrument one day when I was visiting her without my cello, already afraid of playing for her. She asked that wouldn’t I want to play something on her cello and bow that were in the corner of her living room. I managed to make it through the first movement of the Shostakovich’s 1st Concerto, but in the middle of the second movement I had to beg her to let me stop. The experience of trying to play just like her on her cello and bow was too much for me, I just couldn’t go on. That was the last time I ever played for her. It may actually have been the last time I saw her. As her speech was more and more difficult to understand, I was just too embarrassed to ask her to repeat everything two or three times and felt forced to stop visiting her.

I don’t think one should compare Jacqueline du Pré’s recording of any piece to anyone else’s, nor discuss whether her way was right. This is true more than anything in the case of the Elgar Concerto. The fact that many cellists have taken her wonderful and unique performance of the Elgar Concerto as a gospel, copying aspects of her performance, has made most of todays performances of it a caricature of the piece. Talking about her performance without talking about her is impossible.

Listening to her playing, it sounds like all composers were one and the same and writing about her life. The music of some composers lends itself better to her story than others. Which one fits best is anyone’s personal judgment. Like so much about her, none of her recordings should be used as a model for anyone else.

For most people it is hard to imagine to what point William Pleeth was important to Jackie throughout her life. He was part father, part teacher, part colleague, part therapist to the very last days of her life. There was a special tenderness in the way she pronounced his name. Once, I brought a live recording of the Mozart G-minor String Quintet with Pleeth and Eli Goren for her to listen to. Pleeth’s personality comes across instantly and every time he produced one of his recognizable gestures, she would say tenderly “Bii-iilll…” like he had done something naughty. Mr Pleeth was also my principal teacher at the time, but I hadn’t dared to tell him about the lessons with Jackie. One day I got caught like a little boy stealing cookies; I had asked Jackie to write me a letter of reference for a grant application in Finland. I had no idea when she handed me the letter that she had never written a letter like that and had asked Pleeth to dictate it to her the night before. Next time when I went for a lesson with Mr Pleeth, he mischievously said “So, you’ve been seeing Jackie…”. He didn’t mind me seeing her at all, but surely enjoyed seeing my face sink in embarrassment.

Jackie would often ask me to come for lessons either just before or after lunch and have me eat with her and feed her. That of course was another very dramatic experience for a very impressionable boy; the fact that she had to be fed her because her hands and head trembled so much made her tragedy very palpable. After lunch we would invariably listen to some of her own recordings. She listened to those LPs so much that they got worn out. She claimed that EMI wouldn’t give her new copies so I had my parents buy all the copies of her Chopin and Franck sonatas available in Helsinki so she could have replacements. She didn’t so much listen to the recordings to hear the music again as to remind herself of the personal touches that she left in every measure.

Another matter that left me very troubled at the time was that she would often talk to me about how unkind her doctors were to her or how she wished to avoid having lunch with her nurse who – according to her – was very cruel to her. Since I couldn’t confirm these stories with anyone I had no choice at the time but to believe her and I naturally felt even more desperate to help her. I have later understood that many of those stories were probably results of her advancing illness; in the isolation of her disabilities she would grow quite bitter or even paranoid towards some of the people who most tried to help her. She may have been unconsciously in so much need for compassion that reality became blurred.

Jackie had a very particular and mischievous sense of humour, she would love to embarrass this young boy in front of her with naughty jokes or telling riddles to which it was obvious that the answer was something I could not possibly make myself say. She always had trouble remembering my name correctly, and we jokingly agreed that it was much easier if I would call myself Hansen. I remained Hansen to her until our last phone call.

Actually, I very nearly never even met her. When she answered my letter asking if I could have lessons with her, she had completely miscopied my name and address. The envelope read: Mr. Anno, Aloue, 156, Helsinki. The fact that there are only two streets in Helsinki with numbers over 150 made the mailman – after several weeks – try my parents’ house. So I really have to thank the resourcefulness of that mailman for this very important encounter.

Erkki Rautio – the maveric

I should have started by talking about Erkki Rautio, but in fact I have only come to understand and analyse his significance in recent years, once we started playing together and became close friends. The problem in analysing one’s teachers is that the relation is so different as an immature teenager than those few essential years later. One is also tempted to believe that because one wants to move on and have new influences one would be moving away from the early influences. That is of course not the case. Even our earliest teachers of whom we may have no clear memories are with us all our lives somewhere in that complex unconscious that forms an adult person.

I should mention a few words about the situation of cello playing in Finland in my youth. The cello was the only instrument then in which we had internationally known Finnish soloists. There were two; Erkki Rautio and the somewhat younger Arto Noras, they both taught at the Sibelius Academy. Regardless of what either of them might have wanted, as a student you belonged to either one camp or the other. In the cafeteria or in concerts the two students would not mix and you would spend a lot of energy reasoning why the other camp had it all completely wrong. This was something that I could not bear in the long run and it contributed to my early decision to leave and study abroad and finally never move back to Finland. Although the music scene in Finland has developed enormously – and while there are many wonderful young string players – the situation among cellists seems to not have changed much, it still remains divided, or at least is a taboo not to be discussed.

In any case, for me things were clear, I knew early on that I wanted to be a student of Erkki Rautio and became one at 15. He must have been exactly the right person for me at that moment; a strong personality, a maverick. Even if our relation was sometimes conflictive, his absolute honesty and idealism helped me enormously. One of the most important lessons from him was to believe in oneself and yet be one’s most ruthless critic. It was very rare (almost unheard of) to get an unconditional compliment from him. I think he may have said something positive about made my debut with the Saint-Saëns Concerto in 1977, but what I remember is that the first thing he told me was that I didn’t even tune my cello correctly. I am still afraid that I don’t get my cello in tune in concerts. He is a musician to whom it is impossible to give a compliment, he will always find a self-deprecating argument that makes one ashamed of even trying to compliment him.

I am very lucky to have had the courage in the late 1990’s to call Erkki and ask him to play a duo concert with me. This was over 20 years after I studied with him, in the meantime we had hardly kept in touch. A new chapter started, concerts, readings and CDs, from which I have learned so much and which has helped me to look at all my teachers in a new way. It is a luxury to have a friend like Erkki who I can still trust to give me an absolutely honest opinion, be it about a piece I play or my own playing.

Siegfried Palm, Malcolm Bilson and John Hsu

Siegfried Palm was the only cellist with whom I had the chance to study contemporary music. That lesson lasted one and a half hours. I happened to be in Helsinki in 1982 when Palm was playing the Zimmermann 2nd Cello Concerto at the first Helsinki Biennale (which would later become very important festival to me in more ways than one). He also gave a master class at the Sibelius Academy on modern cello music. As no cellist had applied, Erkki Rautio asked if I wouldn’t want to take part. Of course I did. As I didn’t have anything prepared, Siegfrid Palm mainly demonstrated himself what different composers like Penderecki, Zimmermann or Ligeti had written for him and also some classics like Webern. They were only names to me at that point, but his first hand experience made them real persons. His enthusiasm was the trigger I needed to realise that a life in music without living composers is no life. He was the proof that there is nothing as exciting as being part of the creative process, having the privilege of being the messenger for composers.

While William Pleeth had already introduced me to baroque and classical styles, I never actually studied the early instruments with anyone. I did have the luck at the end of 1980’s to get to know two wonderful early music specialists who both lived in Ithaca, NY; the pianist Malcolm Bilson and the cellist and gamba player John Hsu. With Tuija Hakkila I made two trips to Ithaca, during the first we played all the Beethoven Sonatas to Malcolm Bilson. At the second visit we played all the Schumann pieces to Malcolm and I played all the Bach Suites to John Hsu. The way these musicians showed me how to look at these pieces as cycles and to read the manuscripts and the context of every piece once again pointed a new way of looking at music. I understood how essential it is to look for the context and understand how a piece belongs to a continuity. Before I met John Hsu I had no idea how much information one could find in Anna Magdalena Bach’s manuscript copy of the Bach Suites. In those very intense two days, all that I had previously understood and learned about the Suites found its context and I could look forward to a life in music with less mysteries.

— —

Since I only had private lessons with all of my teachers abroad, I met very few fellow cello students and made almost no cellist friends. The friends I eventually made came from all fields of life and art. Partly because of all the time spent on my own those days, friends have become my most valued possession with whom I nowadays stay in constant touch, even if I can’t meet them as often as I would wish. My teachers were wildly different personalities and came from very different backgrounds, I can’t imagine what would have happened if they were all in the same room. From these crossed influences I learned to be friends with people who may not see eye to eye with each other, but who help me to keep my own eyes always open and try to understand the reasons behind even the most conflicting opinions. Friends have become my teachers today.

Teachers plant seeds, but don’t have much influence on which ones will eventually germinate. The ones that do find fertile ground become the building blocks of a real musician and in that they are all equally important. At times I have felt that one of my teachers gave me more than the others, but in the end that is not true. One can’t judge the importance of a meeting by its duration, either. If you took any one person out of this story, the end result would be someone completely different and hopelessly incomplete.

Subjects: Artistic Vision, Artists

Tags: great cello teachers, teachers, Teaching