A Cello Journalist’s Journey

Tim Janof

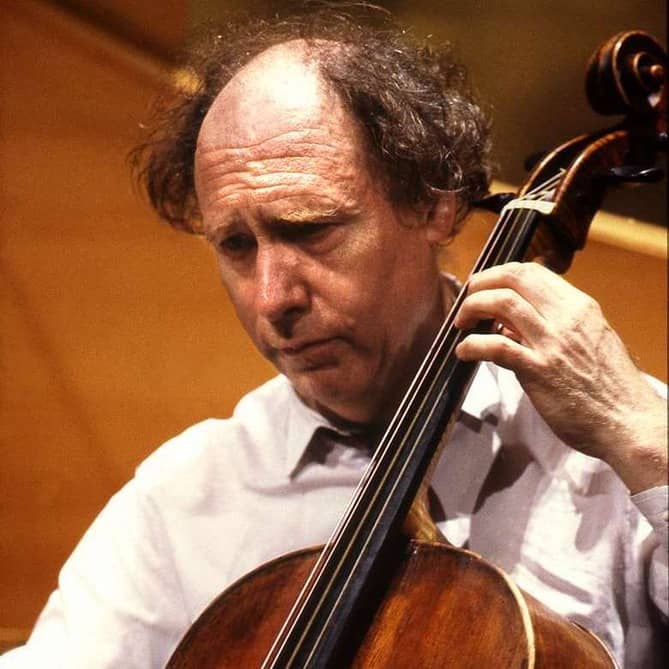

In 2001, I found myself sharing a taxi with Dutch cellist, Anner Bylsma, who was perhaps best known and loved for his performances and recordings of the Bach Cello Suites. We were on our way to the Royal Northern College of Music’s Cello Festival in Manchester, which was the première cello celebration in the world at the time. As we discussed what his detractors were saying about his book, Bach, The Fencing Master, I couldn’t help but note how surreal it was that this was actually happening – that I was spending time with one of my cello idols. It had been 15 years since my cello professor and former Leonard Rose student, Toby Saks, had first played his revelatory 1979 Bach Suite recording for her studio. Having grown up on Pablo Casals’ more earthy rendition, Bylsma’s velvety, sonorous tones transported me into spine-tingling ecstasy. Anner Bylsma’s Bach had changed me, and there he was, right in front of me.

This moment was not just happenstance, however, it was but a moment in time in my own cello journey while documenting some of the greatest cellists and cello pedagogues in the world, including Janos Starker, Mstislav Rostropovich, Lynn Harrell, Zara Nelsova, Steven Isserlis and roughly 80 others. It was the result of countless hours in front of a computer, editing interview after interview, following a strict one-page-per-day regimen and often more, as I became absorbed in the material. It was also the result of standing on the shoulders of giants.

My journey began with David Blum and his 1980 book, Casals and the Art of Interpretation. His book demonstrated that one could write and talk about music in a palpable and therefore helpful way. As luck would have it, David Blum lived near Seattle, my hometown, so Toby Saks invited him to give a presentation on Pablo Casals to her studio. It was after his presentation that I privately asked my very first hard-hitting interview question, as an 18-year-old: “If Pablo Casals was so great, why doesn’t anybody play like him anymore?” Mr. Blum loved my question and wished I had asked it publicly. He responded to the effect that while tastes change, Casals’ greatness transcended time. I would later go on to ask impertinent questions of others, such as asking Janos Starker, ‘What’s wrong with getting excited?’

My next inspiration was Eva Heinitz, who was my primary cello teacher. She had been classmates with Gregor Piatigorsky and Raya Garbousova in Hugo Becker’s class in Berlin, and had played string quartets with physicist, Albert Einstein. She was known for touring with both the cello and viola da gamba and was called ‘the Wanda Landowska of the Viola da Gamba’. She raised eyebrows in the then-nascent Early Music community when she sheepishly added an endpin to her viola da gamba, though with her friend Paul Hindemith’s blessing. She had grown tired of her instrument slipping through her gowns during performances. Imagine my good fortune to have the opportunity to study with someone of her historic stature.

My lessons with Eva Heinitz began when she was in her late eighties, when, to put it mildly, she had established her own fully formed ideas about how music should and most definitely should not be played. She was the perfect person to propel me along my path, because she infused in me a point of view that provided a solid basis for comparison when listening to other musicians. In other words, without her influence, which shines through in many of my questions and comments, I may not have ended up in that taxi with Anner Bylsma.

It was during this time that I became President of the Seattle Violoncello Society. Part of my duties was to put together the Society’s newsletter, a task that I poured myself into. Instead of being just a place for local announcements, I wrote articles, polled Seattle Symphony cellists on questions like, ‘Is there such as a thing as a wrong interpretation?’, and I did my very first interview with David Tonkonogui, a wonderful Russian cellist in the Seattle Symphony. I was trying to generate ‘flow’ in Seattle’s cello community.

In 1995, as my activities were winding down with the Seattle Violoncello Society, I was called by John Michel, cello professor at Central Washington University, who had just founded the Internet Cello Society. He had been reading my newsletters and thought my work would be a good fit for his fledgling group. At the time, I didn’t even know what the internet was – very few people did – but I agreed to give it a try. At first, I would write articles and send them to him on floppy disks through the postal service. Who knew the internet would become so pervasive?

The great thing about the internet is that there are no printing costs, so there were no length restrictions. I could let my subjects tell their story and share their thoughts for as long as they wanted. In my interview with 1966 Tchaikovsky Silver Medalist, Stephen Kates, for example, I knew that he was terminally ill, so I let him talk for as long as he could, and talk he did, resulting in my longest interview (roughly 24 pages). The internet was the perfect venue for long-form conversations.

My interviews started out as essentially a data collection project. In the beginning, I asked the same questions of each subject with the idea that someone would come later to analyse the variety of opinions. I was looking for guiding principles that would help the reader (and myself) reach a higher level. I made discoveries along the way that I found helpful, like the seemingly bizarre notion of time travel, but that is the subject of another article.

I found the Bach Cello Suites to be an endless source of great material, though after a while, it began to feel as if Bach were the third rail of forbidden dinner topics, after religion and politics. Former New York Philharmonic cellist and historian Dimitry Markevitch said of Bylsma: ‘I like Bylsma very much, and I think he does a lot of good, but I don’t agree with his latest approach.’ In the taxi, Bylsma said in response to Markevitch: ‘Who is he anyway?’ And Arto Noras perhaps spoke for many when he said: ‘I prefer not to perform Bach these days. It has become too complicated and too controversial a subject.’ Yes, I occasionally played people off each other.

I’ll never forget sitting across the table from Mstislav Rostropovich, trying to keep my composure while on the verge of tears. Here was the man who had famously collaborated with Shostakovich, Prokofiev and Britten, to name just a few composers who dedicated over 100 works to him. Here was the man who stood up against the Soviet system to defend author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and the one who played Bach in protest at the Berlin Wall. My challenge was determining which questions to ask someone who had been interviewed thousands of times. With Zuill Bailey’s help, I went into the interview well armed. I only had 20 minutes with him, and the interview would be slowed by the use of an interpreter, so I had to make every second count. Though he kept meandering to his standard talking points, there are some gems in that brief exchange, like why he avoided the Elgar Concerto, a piece he considered ‘somewhat naïve’. He died the following year.

I found Janos Starker so fascinating I interviewed him twice (Steven Isserlis too). The combination of his hypnotically penetrating eyes, introversion and brief but self-contained answers were irresistible. There seemed to be no question he hadn’t already considered for decades, which meant he was able to distil his thoughts into as few words as possible. It was as if he were reciting canons, leaving little room for discussion. ‘If you get excited, you lose control.’ Next question.

There came a point where my mission changed from mere data collection to documenting history. Not only was I documenting the person I was talking to, but I was documenting their teachers as well, such as Mischa Maisky enthusing about his studies with both Rostropovich and Piatigorsky. I also realised that my bucket-list interview subjects were ageing, so there was an increased urgency to talk to as many as I could before it was too late. I feel so fortunate to have documented cellists such as Laszlo Varga, Aldo Parisot, Orlando Cole, George Neikrug, Gerhard Mantel, Eleonore Schoenfeld, Dimitry Markevitch, Siegfried Palm and Bernard Greenhouse. My biggest regrets are that I missed Leslie Parnas (1962 Tchaikovsky Competition Silver Medallist), Robert LaMarchina (former Feuermann student and Chicago Symphony Principal cellist) and Harvey Shapiro (former NBC Orchestra cellist under Toscanini).

After doing interviews for many years, I started noticing others were doing interviews very similar in format to mine. What kept me grounded in the face of this was my discovery of Samuel Applebaum’s amazing The Way They Play book series, in which he interviewed legendary musicians, such as Fritz Kreisler, Jascha Heifetz, Pablo Casals, Gregor Piatigorsky, and other luminaries. His books were written in the 1970’s, 30 years before my interviews, and I had unwittingly copied him! It’s true, there is nothing new under the sun.

I feel so fortunate to have been able to spend time with my cello heroes. They serve as my inspiration to this day. I am excited that CelloBello agreed to house the Internet Cello Society archives so that the stories of cellists of my generation and before will not be lost. I am also gratified that CelloBello continues to document today’s cellists, though also in a video or live chat format. Our cellistic youth need to hear the stories of their own idols.

Tim Janof’s interviews can be found at CelloBello.org.

Subjects: Artistic Vision, Interpersonal Relationships