A Profile of Robert LaMarchina (January, 2004)

Tim Janof

by Tim Janof

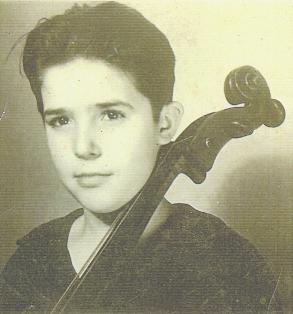

Though relatively few may know of him today, Robert LaMarchina was one of the most brilliant cellists of the 20th Century. A child prodigy, he was the toast of the music world and was showered with praise from some of the most celebrated musicians of his time. Gaspar Cassadó said that LaMarchina was “the most outstanding talent I have seen.” Maurice Maréchal said “There is no doubt of it, the boy is unusually gifted.” Toscanini referred to him as “my little angel.” Had he not gone into conducting and had some self-sabotaging tendencies from a career standpoint, there is little doubt that he would have been a household name for cellists around the world.

LaMarchina was born in New York City on September 3, 1928. His parents had first met on a ship that was headed for the United States from South America, his father being from Argentina and his mother from Brazil. LaMarchina’s father, Antonio, a cellist, soon joined the St. Louis Symphony and moved the family to St. Louis, where Antonio remained for 27 years. At age 3, LaMarchina’s mother left, and there are various theories as to why. It was said that she left because her husband was abusive. Others say she left because she was disappointed in what she perceived to be her less-than-exciting life. A part of Brazilian aristocracy, she had mistakenly assumed that professional musicians traveled in more glamorous circles than they actually do. She left her little son behind, some say because her husband refused to give him up, which resulted in him being subjected to an unhappy series of step-mothers and several new siblings with whom, except for one sister, he felt little connection.

LaMarchina’s father was his first cello teacher and a strict taskmaster, especially once he determined that his son had a special talent for the cello. He made little Bobby, only seven years old, practice several hours each day. He wouldn’t let his son play sports, except for a little soccer, because he was afraid that his son’s hands would be injured. As an example of the rigor of young LaMarchina’s technical regimen, Antonio insisted that his son play scales so slowly that a single run-through of a four-octave scale had to last a minimum of twenty-five minutes. If it didn’t, he had to do it again. The result of this painstakingly detailed work was that LaMarchina had exquisite bow control and a sparkling left-hand facility, but a lost childhood.

LaMarchina’s next series of teachers is a Who’s Who of cellists: Maurice Maréchal, Emanuel Feuermann, and Gregor Piatigorsky. In 1939, he studied with Maréchal after winning a scholarship at the Paris Conservatoire, but this was cut short by the start of World War II. He then studied with Feuermann for three years at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia and in California during the summers. LaMarchina quickly became one of the master’s favorite students. “Once, [Feuermann] tried to fool Eva [Feuermann’s wife] by having both Bobby and himself play passages on his cello. It was very difficult distinguish who was playing.” 2 Eva later told one of LaMarchina’s former students that the same guessing game was played at parties at Feuermann’s house, and with similar results. LaMarchina then studied with Piatigorsky at Curtis for several years, the latter describing LaMarchina as having “golden hands.”

- “The image of cute Bobby LaMarchina does return, sitting on his haunches in the cloak room tossing jacks, regarding no one, seemingly illiterate, then in the evening, on the stage of Curtis Hall, concluding a sensually controlled version of Ravel’s Habanera with that insidious upward glissando, so adult, so satisfying, and yes, so musical. He was Piatigorsky’s pride�.” 3

A music critic for the Globe in St. Louis, wrote the following glowing review when LaMarchina was twelve years old:

- “The exact intonation, the fluent, firm, pure sensitive tone which one perceived in the youthful cellist three years ago continues to be basic. But there is manifest now not only the greater power, the more deft adjustment of dynamics and a greater and more direct certitude in evoking the precise shade and color of tone with a compelling quality of inevitability, but also a mature and personal grasp of the music’s form and meaning. Nothing is parroted. The meaning to Bobby LaMarchina is what his astonishingly skilled fingers, and his sensitive bow project.” 4

We do have some insight into LaMarchina’s cello technique from his former students in Hawaii, who heard him play much later in life. According to Joanna Fleming, cellist in the Honolulu Symphony and renowned teacher in Hawaii:

- “He had the most wonderful bow control and a gorgeous sound, a wonderful vibrato, and he was very virtuosic. He could play anything and just go zipping up and down the instrument like it was a toy. He liked to drum his fingers on the table and show off how they’d thump. He didn’t press hard, though I think he thought he did, because his hand was actually quite relaxed. He’d hit the fingerboard and then release the tension immediately. I remember watching him play the Weber Adagio and Rondo and he played it the fastest I’ve ever heard, but his fingers barely moved because they were so close to the strings. I’ve never known anyone who possessed his mastery of the instrument.”

At age 15, and against his father’s wishes, LaMarchina decided to audition for the NBC Orchestra under Arturo Toscanini and drove to New York by himself. His father didn’t want him to audition, perhaps because he wanted his son to pursue a solo career instead. LaMarchina won the audition and became by far the youngest member of the orchestra, which created a sensation in the media. Even Toscanini was charmed by him, calling him “my little angel.” This was particularly notable because Toscanini was known for never showing any hint of favoritism toward any member of the orchestra. Toscanini once patted LaMarchina on the head on his way off stage, an uncharacteristic gesture that caused quite a stir amongst the young cellist’s colleagues.

LaMarchina’s perspective on his experience in the orchestra was somewhat less glowing. Though he loved playing with such an esteemed group, he found Toscanini’s tantrums to be terrifying. The following comes from an interview with LaMarchina in 1945:

- “It happened during a rehearsal. Something went wrong in the cello section. Toscanini, trembling with repressed rage, strode slowly over to the [cellists]. They looked in consternation for the object of his wrath. The conductor’s eyes had a wide spread, and seemed to cover all the cellists. ‘You!’ he shouted, ‘You! If you were a woman, I wouldn’t marry you!’ ” 5

The cellists never did figure out which of them was in trouble.

LaMarchina also felt isolated while in the orchestra.

- “All I have to do now is to learn to play gin rummy and hearts and I’ll be one of the gang, but they aren’t my age and it gets lonely anyway.” 6

He also grew tired of being in the spotlight because of his youth. People in the audience would crane their necks to get a glimpse of the ‘boy wonder.’ Sometimes he was “tempted to make faces at them or return a stony stare.”

- “With bleeding lips, I’d try to put in three or four hours [of practice]. If I played even two hours, I was killing myself. But I finally got good enough to get into a marching band without destroying Stars and Stripes Forever.” 7

He learned how to speak Japanese and taught cello lessons in Tokyo at the Ueno Ongaku Gakko (Ueno Music School). He also told someone at the Fujiwari Opera Company that he would like to conduct. “They asked if I ever had. ‘Oh yeah,’ I said. I lied.” He assumed that he would have a month to prepare. Instead, he only had five days; a conductor got sick. For his debut, he conducted Puccini’s Madame Butterfly and became to the first Westerner ever to conduct the opera company. He remembered it as the slowest Madame Butterfly in history. “It lasted three hours forty-five minutes. It usually takes two hours fifty-five minutes, including intermission. It went on and on. I’d wait for the singers and they’d wait for me.” 8 Thus began his gradual meandering away from the cello towards a conducting career.

After his release from the Army, he rejoined the Los Angeles Philharmonic and resumed his position as principal cellist, where he served off and on through 1956. In 1951 he met Sylvia Kunin, a TV producer. Kunin had decided to do a television series featuring young talented classical musicians. She had heard that LaMarchina wanted to conduct desperately, and other musicians in the Los Angeles Philharmonic had recommended him. LaMarchina thus became the conductor for what was to be called the Debut television series, which aired every Sunday night for almost two years. Incidentally, Piatigorsky was so impressed with the TV show that, after it went off the air, he urged Kunin to start the Young Musicians Foundation in 1955, which is still active today, and has retained the original TV show’s names “Debut Orchestra” and “Debut Competition.”

In 1960 LaMarchina became principal cellist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) under Fritz Reiner for the 1960-1961 season. Janos Starker, who had been the orchestra’s principal cellist since 1953, had left the orchestra in 1958. Reiner then hired a series of interim principal cellists, including Paul Olefsky, Mihaly Virizlay, and Robert LaMarchina to tide the orchestra over until Frank Miller became available. LaMarchina can be heard playing the famous cello solo in the 1961 RCA Victor recording of the Brahms Second Piano Concerto with pianist Sviatoslav Richter and Erich Leinsdorf conducting the CSO. There is a story floating around that LaMarchina lit a cigarette on stage during the recording session of this work, perhaps as an act of belligerence. According to Phil Blum, who was in the orchestra at that time and still is, too much has been made of this incident, which he remembers as a casual act that occurred during a break.

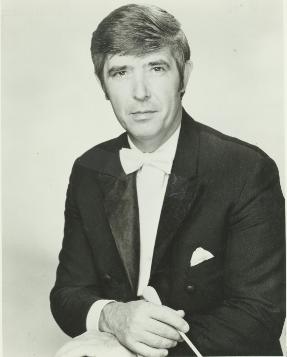

It seems that LaMarchina’s thirst for conducting had grown stronger since the Debut television show went off the air. In 1961, he received a Ford Grant for an intense three-month study course for conductors at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore. His American conducting debut occurred in 1962 with the National Symphony when he was called on to substitute for an ill Charles Munch. He received rave reviews. After such a success, he went on to guest conduct the New York Philharmonic, the National Symphony, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and the St. Louis Symphony. For the 1965-1966 season, he became the musical director of the Metropolitan Opera National Company, and toured approximately seventy cities and university towns across the United States. He also traveled with the “Ambassadors of Opera” and conducted the New York City Center Opera, the Hawaii Opera Theatre, and numerous other companies during the remainder of his career.

Harold Schonberg, the renowned music critic for the New York Times described LaMarchina’s conducting in a review in 1963:

- “He made a favorable impression last night as a musician and baton technician. Fortunately not a slick conductor, he has sturdy ideas about music, and he projects those ideas in a logical, straightforward manner. He keeps good, steady rhythm and has a quality of inner force that keeps the rhythms from being metronomic.” 9

In 1967, LaMarchina was appointed the conductor of the Honolulu Symphony, a post he held until 1978. In 1968 he performed a stunning cellistic feat that is still recounted in disbelief to this day. Jacqueline du Pré had been scheduled to perform with the orchestra but cancelled only three days before the concert was to take place. In what is one of the most gutsy offers one can imagine, LaMarchina volunteered to perform the Dvorak Concerto in her place, even though he hadn’t touched a cello in seven years, didn’t own a cello, and had only three days to prepare. He had to borrow a cello and a solo cello part from one of the cellists in the orchestra. According to Robert Loveless, who reviewed that concert, LaMarchina “turned a major crisis into a rather remarkable musical achievement … he performed brilliantly,” and demonstrated just how ingrained the cello was within his being.

LaMarchina had lots of fans of his cello playing in Hawaii, including Roxie Berlin, who became his student and friend:

- “He played in a piano trio one night, and after the first couple of measures my heart stood still. I’ve heard some really great playing in my day. In fact, I followed Piatigorsky around wherever he played when I lived in New York. But I’ve never heard playing as beautiful as Robert’s. Every phrase was like a bouquet of flowers.”

- “He was something very unique and special. He wasn’t a scholar, and he wasn’t one to research Mozart’s letters or something; it was the music itself that spoke to him. His ability to know how a piece is supposed to go and how to bring it to life was one of his great talents. I always felt ‘This is how a piece is supposed to go,’ when he conducted, and I always felt something in the music when I played for him.”He was the kind of musician who had a piece in his body, and it would just flow out. It was like a phrase was part of his body. He had all the equipment he needed to make it what he felt it should be, and he would share various musical devices in order to show us how to achieve a certain musical effect. But what he couldn’t give us, of course, was his inner Oneness with the piece. He was able to make me play better than I thought I could, just because it was so important to him that we make a phrase happen. It was that kind of conviction that made me want to play my best, because he really cared about the music. This came out in his cello playing as well. “

Fleming feels that opera was his forte, especially with Puccini:

- “He could sing every part in Italian and he knew just how much to bend things, and how much not to, and it was just so much fun to play with him. Singers are sort of visceral, and he was visceral about the way he made music too. It was like the music flowed out of him, it wasn’t just a score that he had studied. He would speed up in certain places and slow down in others because that’s what the music was asking for. It’s one of the great mysteries why he never found a niche in opera.”

LaMarchina was an enthusiastic cello teacher. Fleming, who studied with him for a year or two, described his teaching:

- “He would demonstrate a lot. He could show me how to do something, and how to get a certain effect, and he really cared if I got it. He would make me do something over and over again until I’d figured it out. When I finally did, he said, ‘Look at this,’ and he pointed to the hair on his arm; it was standing up. On the other hand, he had no idea of what was difficult because nothing was ever difficult for him.”

He was extremely detailed in his teaching. In what seems reminiscent of Starker’s teaching method, he talked a lot about different kinds of shifts, like whether one shifts on the departure or arrival bow, and whether one shifts on the departure or arrival finger.

- “I would play something and then he would go back and really dissect my playing, including every shift. ‘Do you want to shift on this finger or that finger? I think you want to shift on this finger and this is why….’ “

LaMarchina believed strongly in having his students do lots of scale work and playing the lesser concertos, like the Davidoff and Goltermanns. There is a story about him getting in a heated argument with another well-known pedagogue about whether students should practice scales. The other pedagogue did not believe in them at the time. Finally the argument boiled down to who their teachers were. He asked the pedagogue with whom she studied. She replied, “I studied with Margaret Rowell.” He replied, “Well, I studied with Feuermann and Piatigorsky!” It is unclear if this settled the argument, but scale work had certainly done wonders for him. In 1995, he was honored by the Eva Janzer Memorial Cello Center at Indiana University with the prestigious Chevalier du Violoncelle.

After LaMarchina’s time with the Honolulu Symphony ended in 1978, he spent the last twenty or so years of his life in relative quiet. He had the occasional conducting gig, but these tapered off, and he also taught cello lessons, but students came less and less. In what seems like a sad turn of events, he essentially disappeared off the music world’s radar, though he occasionally re-emerged briefly before fading away again.

It seems that there are several factors that can be attributed to this. Of course, his cello career faded because he went into conducting. Had he stayed with the cello, there is little doubt that he would be a household name for cellists around the world today. Many theorize that he may have stayed with the cello had his father not pushed him so hard as a child. Other factors include his settling in a remote island in the Pacific (i.e. Hawaii), his feelings of alienation from the priorities of today’s music world, his difficult personality, and his history of womanizing.

LaMarchina was disenchanted with how music conservatories were churning out technically brilliant students who didn’t comprehend the art of phrasing. According to Joanna Fleming:

- “He had a different sort of mentality when it came to making music. He brought phrases to life through the art of rubato, a skill that isn’t taught anymore. He felt that today’s musicians just aren’t interested in doing what he did so well, so he didn’t see why he should knock himself out to teach people who weren’t going to listen to him anyway?”

According to everybody that was interviewed for this article, LaMarchina was a difficult man to deal with, and his reputation goes back to the 1950’s if not earlier. Most blame his poor social graces as an adult on the loss of his mother, his overly demanding father, and his lack of a childhood. Sylvia Kunin, now 90 years old, who produced the 1950’s Debut television series with him, was warned about him before they met:

- “Everyone kept saying ‘Don’t start with him, because he won’t come on time.’ He won’t show up, he won’t do this, he won’t do that. But I laid down the law with him when we first met, and he never missed an appointment with me and he was never late. Everything I asked him to do, he did. He did sell a boat without ever asking us that his family and my family co-owned. My husband and I had planned on retiring on that boat.”

Kunin said that LaMarchina’s career-threatening tendencies caused Piatigorsky great anxiety. Piatigorsky, who continued to feel great affection for him, would shake his head, saying, “What are we going to do with Bobby….”

Joanna Fleming described his demanding nature as a conductor:

- “He could be charming, of course, but he got a reputation for being hard to work with. Nobody ever criticized his conducting, but he was a relentless perfectionist. He felt that there was no reason not to produce the best performance possible. He would argue with the manager because he wanted things a certain way. He would go overtime on rehearsal, he wouldn’t care about the schedules, and he didn’t care about production costs.”A lot of the musicians’ hearts weren’t in it from time to time because he was not always very respectful. He would make comments that people resented, but most of the best musicians really felt that he was something very unique and special. He said to me many times, ‘People get so mad at me, but it’s never personal, it’s all for the music.’ “

Roxie Berlin has a similar view:

- “He didn’t learn to get along with people and he didn’t know the meaning of compromise. He fell out of favor with the people who were producing operas and they figured that they would rather give up his talent for the sake of working with somebody who was easier to get along with. This was a tragedy for those of us who appreciate good music.”

According to Joanna Fleming, his later years were pretty lonely:

- “He had a very tragic life. He couldn’t really get along with people very well, so he ended up not having any gigs. Nobody would hire him and he just did nothing for years. When he left the Honolulu Symphony, nobody was pounding at his door. He was not good about calling a manager or anything like that, and he didn’t have any organizational skills. He had always been so much in demand as a child prodigy, and then his past caught up with him and the calls stopped coming. I’d send him the occasional student, and he gave a few recitals, and he did a few guest conducting gigs, but very few and far between.”

He apparently had a voracious appetite for the opposite sex, especially in his younger years, and most who were interviewed for this article alluded to how this may have contributed to the unraveling of his career, since he may have made some unwise choices in whom he “got to know.” According to Sylvia Kunin, LaMarchina told her back in the 1950’s, “I can only tell you that as principal cellist of the LA Philharmonic that after a concert the young women line up around the block to see me. What the hell!” He used to joke with Kunin, who was 20 years older than him, that she was the only woman he knew who he hadn’t slept with. Kunin credited his ability to seduce woman with his looks, “This was, I hate to say it, because it sounds so awful from a 90 year old, a gorgeous hunk of man.”

The general consensus seems to be that, although LaMarchina was a marvelous conductor, his greatest gift was the cello. According to Sylvia Kunin, “This was really one of the big, big cello talents in the world, and he really screwed it up.”

Only two weeks before LaMarchina died, overweight and struggling with emphysema, he acknowledged that he may have made a mistake in going into conducting. He had just shown a student a video of himself playing when he was much younger. After the student left, he said to his wife, “Oh my God, I was good. I should have stayed with the cello.”

Janos Starker, who was one of LaMarchina’s friends, sums up his fascinating and tragic career:

- “Bob was among the most gifted cellists I have ever encountered and a born conductor. I performed with him in Hawaii. He was an intelligent, warm person, who, in his youth, behaved recklessly on occasion and gained opponents in the field. That accounts for the lack of recognition he deserved. Bob’s obsession with conducting prevented him from a major cello career. May he rest in peace.”

1/1/04

2. Seymour W. Itzkoff, Emanuel Feuermann, virtuoso, International Academy of Chamber Music Kronberg, Kronberg, 1995, p. 199.

3. Ned Rorem, Knowing When to Stop: A Memoir, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1994, p. 171.

4. Harry Burke, Globe, May 13, 1940.

5. Alvin H. Goldstein, Everyday Magazine, St. Louis, March 5, 1945.

7. Dale E. Hall, The Honolulu Symphony: A Century of Music, Goodale Publishing, Honolulu, 2002, p. 99.

9. Harold Schonberg, New York Times, December 20, 1963.

Roxie Berlin

Joanna Fleming

Nicholas Anderson

Subjects: Artists