Two Minutes of Your Time

Brant Taylor

Early in 2011, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra will hold auditions hoping to fill two vacancies in our cello section. In my twelve years of hearing auditions as a member of this ensemble, hundreds of cellists have presented themselves on our stage. Some have done so several times. Their audience is a committee of nine members of the orchestra who sit behind a screen in our otherwise-empty hall. Some of us take notes during the performances, but the only thing that matters to the process is the simple “yes” or “no” each committee member marks on a blank index card after every player has finished. If a candidate receives at least six “yes” votes in a preliminary audition, he or she advances to the final round. To those unfamiliar with the inner workings of orchestra auditions, this method may seem to be a strange and even crude way to evaluate the various facets of a living, breathing musician.

Though some orchestras choose to streamline their audition process by screening applicants and inviting only certain players to attend, the CSO chooses not to do so. We will listen to any candidate who wishes to play. (I’ve occasionally wondered if, under these guidelines, I could apply and be granted an audition time for, say, a trombone audition.) While it’s tempting to think that each candidate has the same aim in any audition—to be offered a job—I don’t always assume that this is true. Some musicians appear to espouse the idea that one should take every audition possible in an attempt to “gain experience” in audition-taking. Future discussions of audition preparation will reveal why I disagree with this practice as a means of increasing one’s chance of success.

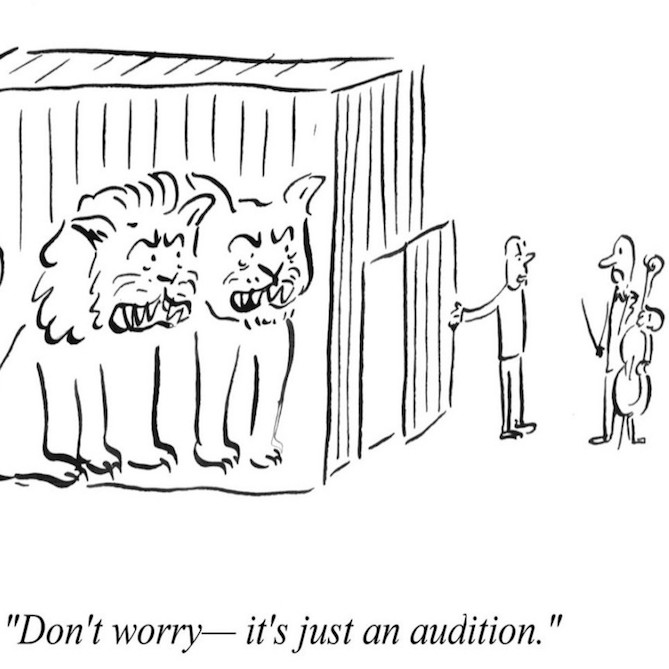

Hearing large numbers of auditions back-to-back makes it possible to perceive basic trends and common areas where candidates can excel or fall short. After a less-than-successful performance, I often wonder about the player. What did that person think about his or her audition? What led the candidate to make the choices he or she made? Although the anonymity which is crucial to our preliminary audition process prohibits contact between the committee and the candidate, here’s an intriguing thought: if I had just two minutes of each candidate’s time one hour before he or she steps onstage to play, what would I say to them?

“Welcome. Not so many years ago, I was exactly where you are right now. I remember that myths float around on the audition circuit about what is or is not required to win an audition. Let me assure you that there really is no hidden code to crack, no secret knock needed to get through the door. All we are looking for is someone with valid, sophisticated musical ideas and the technical means to express them. All the basics of good playing should be inherent in your presentation, but the audition is not ultimately about those things. Rather, say something with the music. We want to see what kind of musical thinker you are, what kind of artistry you can display. Even in the excerpts. The screen may make you feel disconnected from us, but we really are listening and concentrating hard on what you’re doing. We want to hear good playing. We want your best, and therefore we won’t throw you unnecessary curve balls—auditions have enough unknowns already. Here’s a big secret: if you make a really nice sound all the time, no matter what you’re playing, you’ll already be head and shoulders above most of the other candidates. There are countless beautiful and convincing ways to play the opening of the Dvorak Concerto, so please try not to beat up on it. Don’t do battle with it.

“Speaking of the other cellists, it’s empowering to realize that even though the large numbers of candidates for an opening with the orchestra can be depressing to contemplate, most of them will find ways to eliminate themselves. You don’t have to ‘beat’ them. Yes, the first minute or two of your playing is important in making an impression on us, but don’t worry about a minor fumble. Get over it and move on—we can tell the difference between a small accident caused by nerves and a general tendency. Given the time and money invested by everyone involved in the audition process, concluding the audition with nobody being hired is a huge disappointment for everyone, including us. Trust in the quality of your preparation and give us your most honest, thoughtful artistry.”

Many facets of the orchestral audition process are worthy of in-depth exploration. This space will do that in the future, as well as cover many other topics I hope will be of interest to the student as well as to the professional musician.

Tags: artistry, Auditions, beauty, Brant, cello, cello section, cellobello, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Concerto, CSO, ensembles, Excerpts, Experience, honesty, nerves, numbers, orchestra, Practice, Preparation, process, Taylor, Time, trends