Reflections on the 17 Beethoven String Quartets: The Middle Period Quartets (Part 2 of 5)

Paul Katz

The Middle Period Quartets

By Paul Katz

It’s been a personal joy for me to revisit the album notes I wrote 45 years ago for the Cleveland Quartet’s recorded Beethoven Quartet Cycle on RCA Victor. The 17 quartets of Beethoven were the core of our 26-year career as we immersed ourselves in research, score study, years of exhilarating rehearsals, two recorded cycles, 30 complete cycles in the major capitals of the world, and literally thousands of Beethoven quartet performances. Musicians generally agree that there is no other music as rewarding or profound in all of western music. These masterpieces have challenged me as a musician and enriched my life -what a privileged existence!

Formed in 1969, the CQ knew only 2 Beethoven quartets for the 1970 Beethoven bi-centennial year, but we joked that we would be ready for 2020! Though the Cleveland Quartet is no longer active, I could not let this special year go by without participating in some way, and so I returned to my notes written between 1975-1980, and reduced and edited them for this series of CelloBello blogs. The original project was voluminous – 3 boxed sets of LP vinyl, with written liner notes discussing each individual quartet. I have taken about 20% of that original project and present it here in a five-part series.

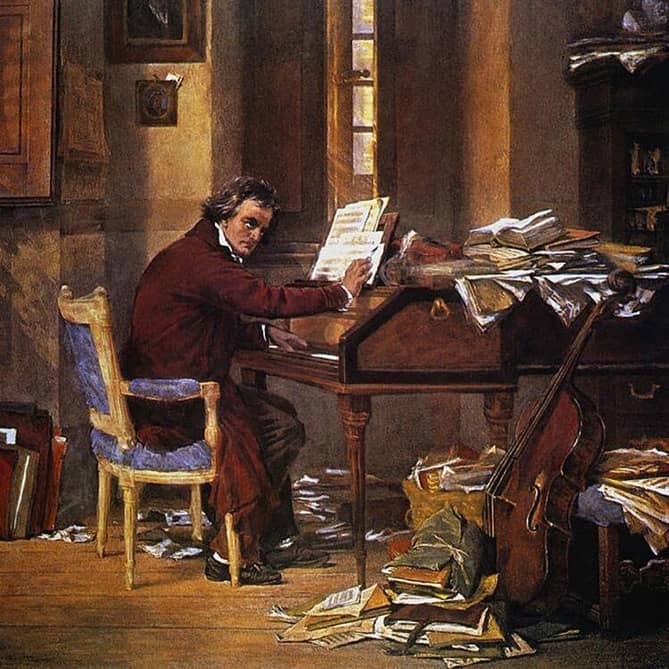

No composer has expressed Man’s deepest emotional states as profoundly as Beethoven. There is a heartfelt depth to the musical experience, an enlightened level of consciousness, a sincerity and nobleness of concept that enriches and inspires. “Those who understand (my music) must be freed by it from all the miseries that others drag about with themselves,” Beethoven is reported to have said. Whether or not he actually uttered these words is ultimately unimportant, for generations have found in his music the noblest and purest expression of universally shared human values such as Love, Joy, Peace and Strength of Character. There is despair and anger, even rage, but never hate, not a cynical or bitter note. Pain and suffering (which he knew better than most are beautifully expressed to us as a necessary part of the synthesis of life.

The Middle Period Quartets (Op. 59#1-3, Op. 74, Op. 95)

From a psychological point of view, the “trigger” experience for Beethoven’s middle period was certainly the crisis of approaching deafness, a trauma of incalculable suffering that led to thoughts of suicide and, fortunately for humanity, Beethoven’s eventual triumph over this personal tragedy:

… I might easily have put an end to my life. Only one thing, Art, held me back. Oh, it seemed impossible to me to leave this world before I had produced all that I felt capable of producing, and so I prolonged this wretched existence, truly wretched… (Heiligenstadt Testament. October1802)

From this point on came a new, more openly emotional form of expression.

These qualities, which were the aesthetic beginnings of Romanticism, reflect more than his personal crisis alone. With historical perspective we can see that evolving political and economic concepts surrounding Beethoven combined in a unique and powerful way with his tragedy. The Revolutions in America (1776) and France (which ended in 1799) were fueled by a new awakening of democratic ideals, individuality, and the rights and dignity of man. Beethoven was not only a creative genius but a man of great moral idealism. This combination of new societal values and his own personal struggle led to his credo of “achievement through heroism in spite of suffering!’ which permeates the works of this period.

The three Op. 59 “Rasumovsky” Quartets, written in 1805- 06, take their name from Count Andrei Kirillovich Rasumovsky, the Russian ambassador to Vienna and an amateur violinist. Rasumovsky occasionally substituted as second violinist in the Schuppanzigh Quartet, a great quartet of its time which premiered many of Beethoven’s works. Count Rasumovsky commissioned these three quartets, stipulating that each one make use of Russian themes. He gave Beethoven a collection of Russian folk tunes, one of which was used as the opening of the finale of Op. 59 No. 1 and another in the third-movement trio of Op. 59. No. 2. Op. 59 No. 3, curiously, has no direct quote, though the brooding e minor second movement may have been Beethoven’s musical expression of the “Russian soul”. These three quartets, each forty to fifty minutes in length, are constructed on a grandness of scale unknown in all chamber music to that point in history. Their structural ambiguities, new hybrid forms, show a revolutionary departure from the traditional classical forms of the first period. The three “Rasumovsky” Quartets were not well received in their time, yet today are the most performed and popular of all the Beethoven quartets.

A cool public reception to the three Rasumovsky quartets may have caused Beethoven to return to more traditional writing in Op. 74. A work of instrumental brilliance and attractive lyricism, it is composed basically along conventional rather than experimental harmonic and structural lines. The somewhat bewildered public response to the “Rasumovsky” quartets was followed by audience acceptance of Op. 74, and its novel uses of pizzicato and brilliant arpeggio writing gave rise to the popular nickname “Harp Quartet”.

By contrast, the “Quartetto Serioso”, Op. 95, was named by the composer himself, is compositionally innovative, unpredictable, and borders emotionally on the schizophrenic. Beethoven heightens abrupt changes in mood with unprepared modulations, omission of normal transition and bridge material, and with a staggering number of shocking and unprepared dynamic changes that alternate between piano (pianissimo) and forte (fortissimo). Written in 1810, one year after composing the Op. 74, Beethoven unexplainedly withheld publication of “Quartetto Serioso” for six years – financially devastating times in which it could have brought him much-needed income. A good friend of Beethoven, a Frau Nanette Streicher, described him in the summer of 1813 as being in “the most desolate state as regards his physical and domestic needs—not only did he not have a single good coat, but not a whole shirt.”

So why did he not publish the quartet? It is possible that he needed time to reflect on this highly involved, experimental work, which in so many ways was a transition piece to the late period.

Continued Tomorrow: The Late Period Quartets (Op. 127,130,131,132,135, and the Grosse Fuge. Op. 133)

Subjects: Chamber Music, Repertoire