A Biography of Gregor Piatigorsky (August, 2000)

Robert Battey

by Robert Battey

One of the pre-eminent string players of the 20th century, Gregor Piatigorsky was born in Ukraine in 1903, and died in Los Angeles in 1976. His international solo career lasted over 40 years, and especially during the 1940’s and early 1950’s he was the world’s premier touring cello virtuoso — Casals was in retirement, Feuermann had died, and the three artists who were to succeed Piatigorsky (Starker, Rose, and Rostropovich) were still in their formative stages. His one true peer, Fournier, was limited in his travelling abilities by polio. Thus, Piatigorsky had the limelight almost to himself. He was gregarious, loved to travel and perform anywhere, and he hobnobbed as easily with farmers in small towns as he did with Toscanini, Stravinsky, rubinstein, and Schoenberg. It was a legendary career.

Piatigorsky was not a “child prodigy,” perhaps, but his talent manifested itself early and carried him quickly upward. He began to play at age 7, and was accepted as a student at the Moscow Conservatory two years later. By age 15 he was principal cellist of the Bolshoi Opera. Escaping the upheaval of the Russian Revolution in 1921, he studied with Julius Klengel (also Feuermann’s teacher) in Leipzig, and at age 21 became principal cellist of the Berlin Philharmonic under Furtwängler. In 1929 he left the orchestra to pursue a solo career. His first marriage (to Lyda Antik) ended in divorce (she later married Fournier!). He then married Jacqueline Rothschild and moved to America in 1939, becoming a US citizen three years later.

He lived first on some property he had bought in the Adirondacks (and helped found the Meadowmount School with Ivan Galamian), then moved to Philadelphia (where he succeeded Feuermann as cello professor at Curtis), and finally settled in Los Angeles in 1950, where he taught with Heifetz at USC. He was a dedicated teacher, and the quality of his studio was legendary. His pupils included Lorne Munroe, Mischa Maisky, Nathaniel Rosen, Stephen Kates, Lawrence Lesser, Dennis Brott, John Martin, Christine Walewska, Rafael Wallfisch, Leslie Parnas, and countless others.

There are too many highlights in his career to mention them all. His annual tours took him throughout the world, appearing with the greatest orchestras and conductors of the time. He made the first recording of the Shostakovich Sonata, collaborated with Stravinsky on his Suite Italienne, premiered the Hindemith Concerto of 1940 and Sonata of 1948, and commissioned or premiered many other works including the Walton Concerto in 1957. He was also a prolific arranger, and many of his transcriptions are published and performed the world over. Piatigorsky always loved chamber music, and was a member of three different piano trios – first with Artur Schnabel and Carl Flesch, next with Vladimir Horowitz and Nathan Milstein, and finally with Artur Rubinstein and Jascha Heifetz!

Piatigorsky’s recording career was fairly prolific, if somewhat spotty. His earliest recording, the Rococo Variations from 1925 on Parlaphone, already displays a well-formed sense of style and virtuosity, an “electric” sound that would become his hallmark. In the 1930’s and 40’s, he did most of his recording in London, for HMV or Columbia; in the 1950’s and 60’s he was an RCA artist. Among his finest solo recordings are an especially beautiful Don Quixote with Munch and the Boston Symphony, the Brahms E minor Sonata with Rubinstein, the Walton Concerto with Munch, the Debussy Sonata with Lukas Foss, and many of his short pieces from the HMV period. The specter of Casals kept him (and his classmate Feuermann) from recording any solo Bach, but otherwise his recordings covered all facets of the repertoire: Beethoven, Brahms, and Strauss sonatas, Dvorak, Saint-Saëns, Schumann, and Brahms Double concertos, encore pieces, etc. The bulk of his work for RCA consisted of chamber music recordings with Heifetz; they focused on works with piano or string repertoire other than quartets.

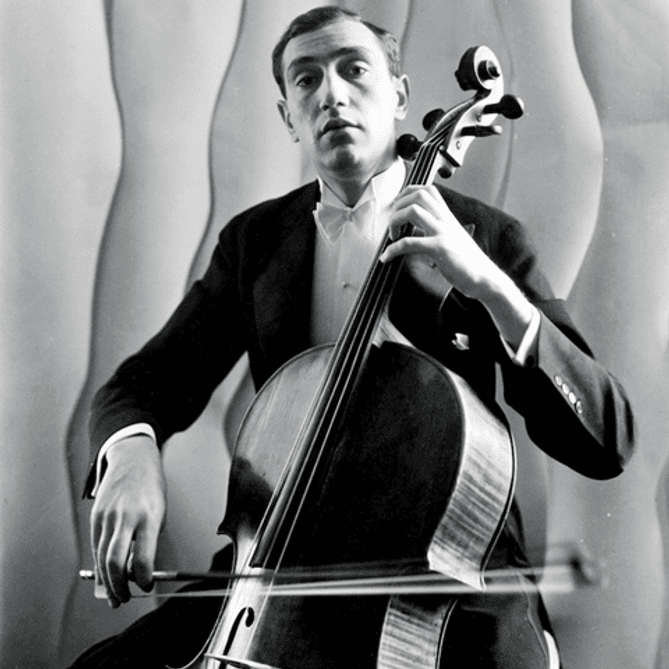

Piatigorsky was a very tall man, well over six feet, and he handled his Stradivarius like a toy. He would stride briskly onstage through the orchestra, holding the instrument horizontally with one hand, like a lance. He often closed his eyes and turned his handsome face to his right as he played, giving a regal bearing to his performing profile.

Due to his size, all the basic playing actions were simple for him; he had a huge sound, and drew full bows with same effort and extension that a smaller player like Casals needed for only half the bow. He could produce the widest spectrum of colors, from any spot on the bow. He delighted in quick changes of articulation, even if just for a few notes. Most dazzling of all was his staccato stroke, which is wonderfully showcased in a Kultur video entitled “Heifetz/Piatigorsky.” There, in an arrangement he made of some Schubert Variations, he displays both a down- and up- bow staccato that is almost beyond belief, along with many other signature effects. His own set of variations on the famous 24th Caprice of Paganini is a minefield of specialized bowing challenges; no one has been able to play it with his ease and flair, though many have tried.

His left hand too was a law unto itself; reaching 1-4 octaves in the lower positions was easy and natural for him, and he ambled nimbly and effortlessly around the fingerboard. Trills were, again, “electric,” and he drew incomparable richness from the lower strings. However, not all listeners were taken with his vibrato. Given his size, he apparently had trouble controlling the full-arm motion that most cellists learn, and was more comfortable producing the vibrato from a wrist motion alone. This gave the sound a nasal quality at times. And, since he had to work less hard to produce the vibrato, he did not always attend to it with the care that someone with more ordinary gifts would, and some passages in his recordings grate on listeners brought up on the buttery sounds of Rose or Fournier. In his later years, this technique also began to effect his intonation. On balance, though, his playing displays a combination of stylishness, verve, and humanity that no one has ever matched.

All of Piatigorsky’s concerto and chamber music recordings for RCA are available on CD; there are at least two discs of recital works that have not been reissued, however. Most of the earlier material is also available on various historical labels such as Testament, Biddulph, Arlecchino, and Pearl. Interesting historical tidbits include the octave-jumping in the repetitive bridge passage leading into the 5th Rococo variation (1925); the inexplicable blending of pizzicato and arco triplets in the string accompaniment to the slow movement of the Schumann Concerto (1934); the added embellishments in the Chopin Polonaise, much different than the standard Feuermann version (1940); and another version of the passage that now consists of glissando harmonics in the second movement of the Shostakovich Sonata (1940).

As mentioned, the Don Quixote with Munch is one of the greatest recordings ever of the work (which has had many great recordings, all of them on RCA for some reason), and the Kultur video belongs in every cellist’s collection. There is a spectacular BBC film of the UK premiere of the Walton Concerto; God willing, someday they will see fit to make it available to the general public. For me, though, the quintessential Piatigorsky is heard on his live recordings and airchecks, despite sometimes poor reproduction. When onstage he seemed to draw energy and inspiration from his colleagues and from the audience; despite the occasional technical slip the music-making is always white-hot. There is, or used to be, a CD available of Schelomo with Rodzinsky and the NY Philharmonic from 1944. While Piatigorsky forces the sound sometimes, and ensemble is not perfect, it is a spellbinding portrait of a great performing artist at the peak of his powers, captured in full flight. Experiences like that heard on this recording are simply not to be had today; no one gives so much of himself anymore.

Piatigorsky’s legacy is deep and broad. Aside from the transcriptions that we all play, the annual seminar in his name at USC, where gifted young cellists from all over the world come to learn from top solo professionals, and the wonderful recordings and films, above all there is the legacy of spirit. Every Piatigorsky pupil I’ve ever spoken to had only the warmest praise for the man, his teaching, and his devotion to the fullest development of each student. His artistic vision has been passed down through younger artists, and thence to their pupils throughout the world. He has left the music world incomparably richer for having passed through it, and all of us are beneficiaries of his life.

[I am indebted to Dr. Joram Piatigorsky and Ms. Maggie Bartley for background information]

Subjects: Artists, Historical