Martin Berteau

Like the German school of cello playing, the French School had a centuries-long impact, which continues today. When we think of French playing, refinement, finesse, and elegance come to mind, but during the 18th Century in Northern Europe the cello was still considered a lowly, rudimentary instrument compared to the viola da gamba. The French cello school evolved due to the exquisite playing of Martin Berteau (circa 1700-71). Despite maintaining the underhand bow-hold of the gamba, his sweet tone and depth of expression greatly influenced his students, Jean Pierre Duport, Tillière, and Jean Baptiste Cupis. Berteau developed an effortless fingering system, incorporating the use of the thumb, and introducing the use of both natural and artificial harmonics, which was quite unusual for the cello at the time. Cello fingering, he thought, ought to emulate violin playing where each finger plays a half step or semitone.

Cupis, who studied with Berteau from the age of eleven, became the principal of the Paris Opera and was a soloist in Italy and Germany. He and his most well-known student, Jean Baptiste Bréval (1756-1825), advanced the French playing style. Many young cellists are familiar with Breval’s cello compositions—sonatas, concerti, and numerous duos, and trios.

Breval: Sonata op. 12 – I. Allegro

By far the most influential Berteau student was Jean Pierre Duport, “l’aîné,” the eldest (1741-1818). By the time he was twenty, his playing was so impressive he was appointed by Louis François I, Prince of Conti, to perform a solo nightly in his private band. In 1762 the Mercure de France wrote about Jean Pierre, “In his hands the instrument is no longer recognizable; it speaks, expresses, and renders everything with a charm greater than that thought to be exclusive to the violin…” Duport’s travels took him from Spain, to London, and then Berlin, where Frederick the Great hired Duport as chamber musician for the Royal Chapel, principal cello of the Royal Opera, and tutor of the Crown Prince. Once the prince ascended the throne as Friedrich Wilhelm II, Duport became the director of Royal Chamber Music. Through this distinguished position Duport met both Mozart and Beethoven. Mozart’s String Quartets, nicknamed ‘The Prussian’ K575, 589, and 590 and Beethoven’s Sonatas op. 5 for piano and cello, dedicated to the king, seem to confirm Duport’s influence, as these works feature quite advanced technical demands, and the cantabile or smooth singing style of the cello.

Duport: Cello Sonata in D

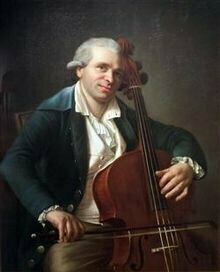

Duport’s talented younger brother Jean Louis (1749-1819) also became a brilliant cellist not in small part due to the elder Duport’s success and his teaching. Jean Louis’ playing was notable for its flowing lines, brilliance, and sweet, yet powerful tone.

Jean Louis Duport © Wikipedia

The younger Duport became professor at the Paris Conservatoire. Duport wrote many works for the cello as well as a method book in which he discusses how to play double-stops—two or more notes at the same time—one of the first cellists to do so. He established a fingering system for mastering double-stops, and he also developed a standard fingering for the chromatic scale. His cello studies are some of the best (and most difficult!)

Jean-Louis’ influence was strongly felt throughout Europe. One of his pupils was the Russian cellist, Davidov. Another, and one of the most prominent, Joseph Platel(1777-1835), is considered the founder of the Belgian School of playing. He was born in Versailles, and subsequently taught for many years at the Brussels Conservatoire. Platel like the Duport brothers was known for his beautiful, supple tone. Platel traveled extensively, inspiring the next generation of cellists.

The cello standards of France were rapidly ascending. German cellists were still playing with a powerful sound, and a facile left-hand technique, but they preferred a solemn, serious musical approach. The French, hailing from the royal courts of elegance, finesse, and refinement, held the bow at a distance from the frog, and tended to lighter bowing. Emulating the style of violinists such as Viotti, French cellists learned agile and intricate bowing techniques—spiccato, (light and fleeting, the bow bouncing off the string) staccato (short notes with silence between them), detaché (smooth separate strokes) and others. These bowing styles and the bow hold of Jean Louis Duport’s time are evident in his delightful Sonata in D. Two other French cellists—one, a student of Platel’s, Servais, and the other Franchomme, are noteworthy.

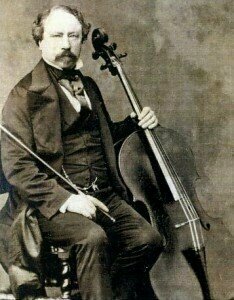

Adrien François Servais © Wikipedia

Adrien François Servais (1807-1866) was a teacher at the Brussels conservatory and a dazzling solo performer. He became Platel’s assistant in 1829. Servais, was known as the “Paganini of the Cello”, celebrated for his brilliant technique, graceful and flowing bow arm, singing sound, and poetic interpretations. He adopted violin-like left hand fingering, and his compositions reflect this technical exploration. Servais is credited with inventing the end pin or spike. Perhaps this was due to the fact that he became quite rotund in later life and couldn’t support the cello anymore. But it revolutionized cello playing. The end-pin allowed more freedom for the arms. One other benefit, though inadvertent, was that it allowed women to play the cello while preserving their modesty and yet not having to sit side-saddle. Beginning in 1839 and returning ten times, Servais was a frequent guest performer in Russia making a huge impact on Russian cellists. His Fantaisie sur Deux Airs Russes, shows what facility he must have had!

Servais: “Fantaisie sur deux Airs Russes,” from Russian tunes

Cellist Sol Gabetta with accompaniment from pianist Ilya Yakushev