Conversation with János Starker (February, 2004)

Tim Janof

Interview by Tim Janof

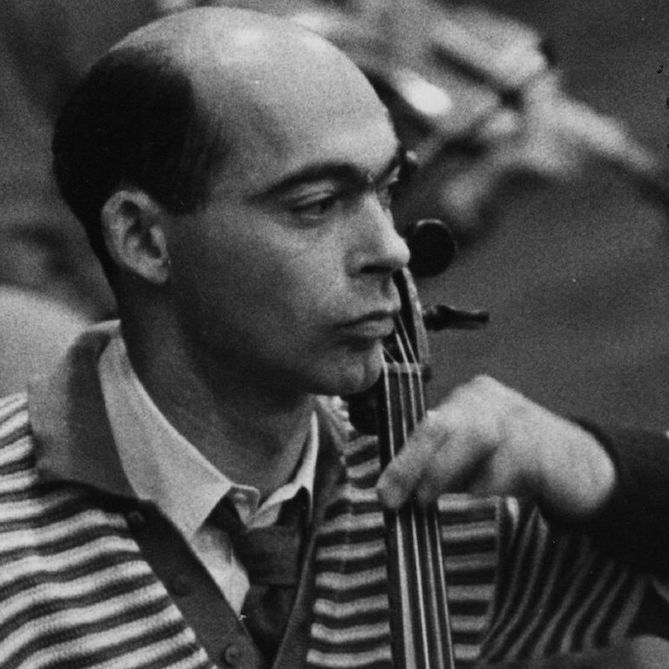

“With his peerless technical mastery and intensely expressive playing, Janos Starker is universally recognized as one of the worlds supreme musicians.” (New York Times)

János Starker was born in Budapest in 1924 and began studying the cello at the age of six. By the age of eight he was coaching his first pupil, and by eleven he was performing in public. His early career took him through Budapest’s Franz Liszt Academy, and on to positions of first cellist with the Budapest Opera and Philharmonic at the end of World War Two. In 1948 he emigrated to the United States where he subsequently held the posts of principal cellist with the Dallas Symphony, Metropolitan Opera of New York, and the Chicago Symphony under Fritz Reiner.

In 1956 he started his world-wide touring with all the major orchestras as soloist, recording artist, recitalist, and chamber music player. In 1958 he joined Indiana University, School of Music, where he holds the title Distinguished Professor, and the first recipient of the Tracy Sonneborn Award for a faculty member who has achieved distinction as a teacher, as well as performer and scholar.

It was in 1999 that a special gala honored him in Bloomington on the occasion of his 75th birthday; an occasion when he first appeared on stage with Mstislav Rostropovich, who conducted the Brahms Double Concerto with Starker and his son-in-law, William Preucil, concertmaster of the Cleveland Orchestra.

Mr. Starker has amassed a discography of more than 170 works. His last releases on BMB RCA Victor red seal label include the cello version of Bartoks Viola Concerto, Dvorak, Hindemith, Schumann, Elgar, and Walton Concertos, Strauss Don Quixote, sonatas by Brahms, Martinu, Rachmaninoff, etc., also his fifth version of the Bach Suites which earned him a Grammy Award for best instrumental solo performance in 1998. Additional releases can be found on Angel, CRI Deutsche Gramophone, EMI London, Mercury Philips, Erato, Seraphim and other labels world-wide. His editions of the major part of the cello literature have been published by Peer International, Schirmer and now by Masters Music Publications.

Since 2001 Mr. Starker has limited his activities to teaching, master classes and occasional performances with his long time partner, the pianist Shigeo Neriki, and his son-in-law, daughter and granddaughter, violinists William, Gwen, and Alexandra Preucil.

TJ: Let’s start with a very basic question. How do you pronounce your last name? It is “Shtarker” or “Starker.” I’ve heard it both ways.

JS: Both are correct. My name means “strong” in German, so those who speak German usually pronounce it “Shtarker.” In the United States, it’s pronounced “Starker,” which is how I prefer it.

My original name was “Starker Janos,” actually, because the last name comes first in Hungary. There was a time in Hungary when the government encouraged those with German names to change them to Hungarian names. My teacher suggested that I change mine to the Hungarian equivalent, “Eros,” and there was one concert in which I was called “Eros Starker Janos,” but I vowed to never do that again and I retained my name as-is. I refused to do it, but others did succumb to political pressure. Eugene Ormandy’s last name was originally “Blau,” which means “blue” in German. George Solti’s last name was “Schwartz.”

People have had trouble with my first name too. Early in my career it was changed to fit whichever country I was playing in, which created some confusion. I was called “Johann,” “Hans,” “Johannes,” “Jean,” or “Jon.” When I played in Romania, they meant to change my name to “Jan” because Romanians didn’t like Hungarians at the time and Jan didn’t sound Hungarian, but the programs ended up saying “Jano,” which led some wags to say that I was Irish — Jan O’Starker.

Laszlo Varga, also originally from Hungary, was sent to a labor camp during World War II. Were you in one too?

I was in an internment camp for three months, not a labor camp. The camp was located on an island in the Danube just outside of Budapest.

You are known for making some pretty controversial statements. For example, you said that the first time you soloed with the New York Philharmonic was not a particularly significant event in your life, given that you had already played with most of the world’s greatest orchestras. One would think that these kinds of statements would be detrimental to one’s career.

I couldn’t care less, and that’s why my new book will be called The World of Music According to Starker. I was just stating the truth as I saw it. I went through hell in my youth because of the war, which I describe in more detail in my new book, and having lived through it I stopped being afraid. I couldn’t care less what others think if I’m speaking out against something that runs contrary to my fundamental beliefs. I don’t play political games, and I never have. I was fortunate in my career in that I was able to retain my self-respect and therefore have the freedom to say anything I felt like.

I have never asked any conductor, orchestra, or concert organization for an engagement because I’ve always felt that what I was doing was good enough and it is they who should ask me to play. That’s why I turned down Leonard Rose’s invitation to audition for the New York Philharmonic’s principal cellist position when he left the orchestra. I was the principal cellist of the Metropolitan Opera at the time, and I felt that they should know who I was and how I played. If Mitropoulos wanted to hear me play, he should have called me himself, instead of making me play for some committee.

I recently completed an article on Leonard Rose, and I was hoping you could fill in a few gaps for me about him. In my first interview with you, you said that Rose was overly focused on the competitive aspects of music. How so?

He felt competitive because he didn’t feel he was getting the number of engagements he deserved. He was a very frustrated individual. He complained that he was never able to have the solo career he had hoped for because Casals and Piatigorsky were getting all the concerts when he was younger, and then Rostropovich, and later I, emerged after they retired. There was never a time when he felt like he was the cellist in the world, which he resented. But then he started to get more engagements and he began playing with Istomin and Stern in the trio, and then he was a little more satisfied. He never felt that he was appreciated, which was ridiculous, given that he was amongst the finest cellists I have ever known. His cello playing and his music making were on the highest level. I nominated him to be honored by the Eva Janzer Memorial Cello Center many years ago, but he turned it down for some unknown reason.

I once compared recordings of the Brahms B Major Trio and I noticed that Rose’s phrases were less arched than Greenhouse’s.

I don’t believe in discussing who is better than whom when talking about the upper ranks of artists. When you reach the pinnacle of artistry, there is a certain group of people that are what we call in French the “de hors” class. These are people who transcend classification. From that moment on, one can like this or that person better, but there’s no question that certain cellists belong to the de hors class, and Rose was certainly one of them, as was Fournier, Gendron, and Tortelier, and a few others.

Let’s talk about your sound, which is very distinct. I realize that you don’t believe in vibrating too widely because intonation can suffer, and that you change your vibrato depending on the overtones of each note. I guess I’m struck by how different your sound is from other cellists, who strive to make each note as beautiful as possible with a sensitive but consistent use of vibrato.

I don’t believe in using so much vibrato. As Bernard Greenhouse said to me towards the end of his time with the Beaux Arts Trio, “It’s very tiring, Janos, to vibrate so much. I’m getting a slower and slower vibrato.”

My intonation is focused and always at the center because I use a narrow vibrato. This is more difficult to do because notes that are out of tune are more noticeable. Many of my colleagues play what might be called “lukewarm intonation,” but it doesn’t bother most people because it’s like being in a lukewarm bath. If everything is slightly out of tune, one’s ears become desensitized to what’s in tune and what isn’t, and a centered intonation isn’t necessary.

I happened to believe that a sound without vibrato can also be beautiful. Sometimes we sing, and sometimes we hum, which we call positive and negative sound, respectively. We shouldn’t always be playing “la la la,” sometimes it’s just “hmm hmm hmm.”

A beautiful sound to me is one that has vocal or other instrumental implications, which I believe distinguishes me from practically any other cellist, living or dead. I consider myself to be the most vocal and instrumental cellist who ever lived, which makes my sound distinct and recognizable. What I mean by this is that my musical approach is to not always sound like a cello. I produce a variety of sounds: soprano, mezzo, tenor, bass, baritone, flute, oboe, clarinet, and so on.

My eleven years of orchestral playing and my time in the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra exposed me to many different sounds. In addition to my orchestral colleagues, I heard the greatest soloists and singers and worked with the greatest conductors of the twentieth century. My experiences inspired me to find ways to reproduce on the cello the sounds I heard.

The only true measure of success as a musician is whether he or she is recognizable. That’s why Pavarotti has had such an incredible career; when you hear Pavarotti, you know it’s him. The same could be said of Maria Callas and Jascha Heifetz. Heifetz has always been my guiding string instrumentalist, not necessarily because of his musicianship, but because his sound was so distinctive. Of course, this isn’t something that one should set out to do, where one consciously chooses certain idiosyncrasies just to stand out, otherwise the music becomes secondary.

There are many instrumentalists today who are superb players, musically and technically Heifetzian in standard. The problem is that I can’t tell who the hell is playing when not looking. Perhaps the only violinist who stands out today is Itzhak Perlman. Oistrakh had a recognizable sound. Stern was distinguishable for awhile. You could pretty much recognize when Rubinstein or Horowitz were playing, but not Michelangeli. Serkin was only recognizable because of missing notes, which he dropped amid the excitement of the performance.

Where did you get the notion, “I am not an actor, I’m a musician”? Did you get this from your own teachers?

No. I’ve never liked theatrics, and I don’t think it belongs in music. I’ve always moved when I play, but people don’t notice it because I move in the direction of the music. Motions are only noticeable if they are contrary to the musical line.

Do you think of yourself as leaning more towards singing or speaking when you play?

I don’t think of myself as doing either, particularly. Instead, I’m transmitting the message of the composer as I understand it, and not by swearing that every note a composer writes is sacred.

I noticed in the Schubert Quintet that even when there’s a long line you play with a lot of inflection and articulation, as if you’re enunciating words.

Within phrases there are different directions and movements that are totally different moods. My interest is to emphasize those character changes, and to not play a phrase the same way twice. And then there is a question of the Viennese element in Schubert. You can play the notes exactly as printed but this doesn’t necessarily convey the mood and character of the music of Vienna.

Eva Heinitz used to say that Schubert’s music should be played as if one has a smile in one eye and a tear in the other.

That’s a very wise description.

Where did you get the notion of consonants and vowels in musical articulation? Did you get this from your own teachers, or did you develop this yourself?

If I were to credit a teacher, it would be Léo Weiner. I had a great cello teacher too, Adolf Schiffer, but he wasn’t particularly analytical. Léo Weiner has been explained by fifty of his former students in a book, but it’s written in Hungarian. Weiner was a great musician, though not an instrumentalist, and a fine composer, known as the ‘Hungarian Bizet.’ He came before Bartok, Kodaly, and Dohnanyi.

Weiner helped us to become aware of the significance of even the tiniest of notes, including their beginnings and ends and what happens between them. He did this by asking for very specific things in chamber music coaching sessions, like to play a note longer or shorter or with a certain articulation or attack. His meticulous method developed our ability to listen to ourselves objectively and focused our attention on the detailed aspects of music making, which many musicians don’t seem to be aware of, even superb instrumentalists and otherwise highly trained musicians.

My job is to continue this process with gifted people who can discern the difference in how each note can be approached. If I ask a student to play a note with a dot on it by detaching it at both ends, or just from the previous note, or just from the next note, and if he or she doesn’t hear the difference, then he or she isn’t the kind of student I’m looking for. These are what one might consider to be the esoteric details that somebody on an extremely high level considers.

If one dwells on the tiniest details of how to play each and every note, might playing music become too much of an intellectual exercise?

Playing music only becomes intellectual when one is trying to explain it, either to oneself or to others. There is a certain analytical process that must be followed when approaching a piece of music — you see a text, you learn a text, and you try to approximate the composer’s thoughts. On a technical level, if you lift up the upper arm, for example, and go to the upper half of the bow without using the forearm, the sound will be destroyed. If you hear the difference, you will change how you play. One must therefore adopt some basic rules and processes, of which there are many, both instrumentally and musically, and once these are internalized, one can go to the next artistic level. Otherwise, one becomes stuck.

This gets back to the age old question, “How do we know when something is right in music?” Some say to just let one’s imagination and talent run free, but I disagree with this approach. I decided at an early age that I was going to be a professional, which means to have the ability to play on a consistently high level from performance to performance under any ‘rain or shine’ situation. “Consistency” is the key word, and one can’t achieve this if one doesn’t know what one is doing. One can’t rely on luck or pure instinct.

When you are performing, do you always try to make sure that you never lose technical control? Truls Mørk talked about experimenting with being on the edge of technical control, at least in his practice sessions. Do you ever try to push the envelope of technical security in order to achieve something more on an artistic level?

“Pushing it to the edge” sounds impressive, but I’m not sure what it means. My focus is to make sure that a composition has a beginning, a middle, and an end, and that the sound is pure. Simplicity, purity, and balance are my goals, not “pushing it to the edge.” Perhaps Mørk was just trying to entertain your readers.

I find it amusing how certain questions keep re-surfacing, as if they haven’t been asked, or answered, before. I’ve learned a lot of musical and technical principals over the past seventy years, and not just from my own cello teacher. I’ve picked things up from several sources, including violin teachers who were more mechanically minded than I am considered. I learned from them to look at all aspects of instrumental playing and music-making. But one must remember that they learned what they knew from others as well. And now several of my students are publishing books and articles on various subjects as if what they have to say is new, when in fact they are passing along principles that I learned from others many years ago. Of course, I rejoice when such things are well-written, but the reality is that there’s nothing new. And yet young people seem to feel compelled to restate things that their predecessors have been preaching for decades or centuries. Then questions like yours come around and young people have to figure out something that sounds interesting and clever, whether or not it makes any sense when one looks below the surface at what’s being said. Maybe this is what Mørk was doing in response to your question.

Always remember that when somebody is as talented as Truls Mørk, he or she can play side-saddle cello and still sound great. This is why I’m not particularly interested in having only the greatest talent in my class, since these people will find their way without me. I’m more interested in helping the people who didn’t have a proper education, who learned to run without learning how to walk first. These people need me to walk them through a step-by-step process of how to play the instrument and how to make music so that they may become professionals. The goal is not to help them play the Dvorak Concerto better than anybody in history, but to prepare them to be able to fulfill whatever musical requirements are asked of them, and to do so in a consistently professional manner.

I’ve certainly had my share incredibly talented students over the years that have succeeded on the highest level, such as Tsuyoshi Tsutsumi, Gary Hoffman, and Maria Kliegel. Of course, I take no credit for their talent; I just helped them to take advantage of it. But what I’m most proud of is that they, as well as hundreds of others, know what they’re doing when they play and they have enjoyed years of healthy, pain-free playing.

Then there are others who didn’t apply my teachings that ended up experiencing pain because they played incorrectly. Eventually, when they get themselves straightened out and start recalling my teachings, they become “experts” on how to avoid pain and they start writing articles and books on the subject.

Do you find yourself maintaining a certain objectivity when you play? Is this part of how you play so well, because you don’t get carried away emotionally by what you’re playing?

György Sebok was the one who said, “Don’t get excited. Create excitement.” This pretty much sums up my approach. I keep my emotions in check so that I may direct my energy towards conveying the message of the composer instead of becoming overly absorbed in my own emotional response to the music. A concert is about the music, not the performer, and a musician can’t improve a masterpiece. At best, he or she can stay out of the way.

When you play a piece such as the Schubert C Major Cello Quintet, do you still find yourself thinking, “This is such great music!”?

That never leaves.

Your playing seems to have an improvisatory element. Do you continue to try out new ideas when you play?

I often speak about the fact that the performing arts are supposed to have a certain element of improvisation in it. But it’s very seldom that anybody truly improvises, where he or she has never tried something before. Instead, improvisation is a selection process. You have four or five different ways of doing certain things, and you pick one because of the circumstances of the performance or how you feel in the moment. It’s very rare that a new idea surfaces while on stage.

Frans Helmerson said that improvisation belongs in the practice room, not on stage.

Don’t believe him. We try a variety of ways to approach a piece in the practice room, but I wouldn’t call this process “improvisation.” On stage, improvisation is a selection from available choices, like picking from a menu. You don’t hear players truly improvise because all the so-called “improvisatory” moments have been practiced. It’s more a matter of which ones they are going to pick. True improvisation only applies to those composers who sat down at the piano or organ, for example, and made up something on the spot.

What process do you go through when you first learn a piece. Let’s say you’re playing the second theme in the first movement of the Dvorak Concerto for the first time, do you analyze a phrase by looking for the peaks and then keep massaging the phrase until you sculpt the phrase just how you want it?

Considering that the first time I played the Dvorak Concerto was in 1938, I can’t remember what process I used back then. By the way, I only had a six-hour notice for that concert, and I had only learned the piece six months earlier. That was quite a day.

I first study a piece away from the cello by reading the score, playing it in my head. After I’ve done this, I play it on the cello. Then, as the years go by, and after I’ve performed it many times, I become more and more sensitive to the possibilities with the orchestra, and what the orchestra’s role is in shaping my ideas. There are other factors that can affect how I phrase in any given concert, like how responsive the conductor and orchestra are, which may require some adjustment on my part. My decision as to how to play a phrase is therefore based on many factors. But new ideas often come to me at night when I’m in bed, especially at this stage of my career, when I’m not really concertizing anymore. Half the night, there is music playing in my head, and that’s when new possibilities emerge.

2/28/04

Subjects: Interviews