Conversation with Ron Leonard (February, 1996)

Tim Janof

Interview by Tim Janof

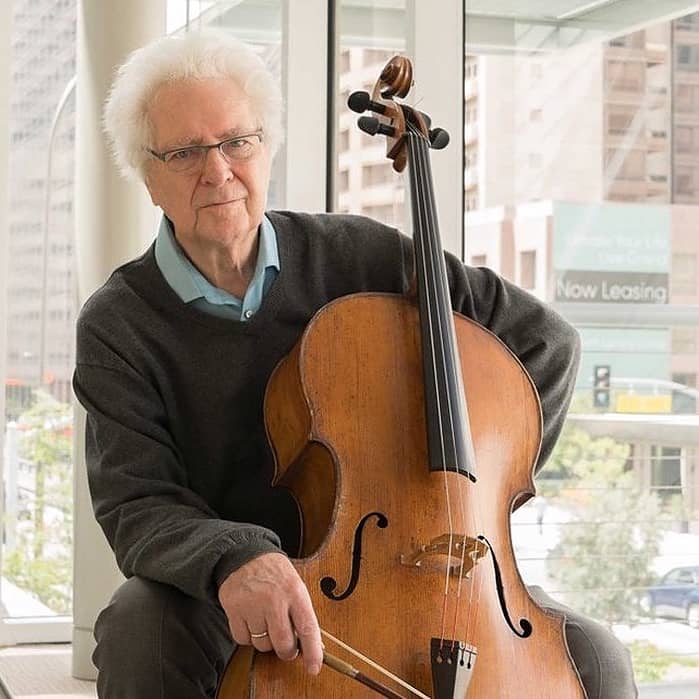

Ronald Leonard is well known as a soloist, chamber musician, and teacher. He has been Principal Cellist of the Los Angeles Philharmonic since 1975, and is the Gregor Piatigorsky Professor of Cello at the University of Southern California. He has performed concertos with Zubin Mehta, Michael Tilson-Thomas, Carlo Maria Giulini, Andre Previn, Simon Rattle, and Esa-Pekka Salonen. He has appeared as guest artist with the Juilliard, Guarneri, Angeles, Mendelssohn, Borremeo, Chilingarian, and American Quartets.

TJ: You studied with Orlando Cole and Leonard Rose at the Curtis Institute. How did their teaching methods compare?

RL: I studied with them at the same time, believe it or not. They were two very different musical personalities. They approached the instrument, both technically and musically, from quite different viewpoints, and their bow arms were very different. Leonard Rose had a suave bow arm with which he created a very big sound. Orlando Cole was much more interested in a refined or Viennese sound. He worked a lot on shifting and had me do a lot of Sevcik exercises.

TJ: Studying with them simultaneously must have been confusing, not knowing whose direction to follow. Did you play differently for each teacher?

RL: Leonard Rose was away on tour a lot of the time. When he wasn’t there, Orlando Cole took over his class. Though their teachings differed, neither criticized the other’s ideas.

TJ: Would you say you benefited from this experience, since you were exposed to different, though equally valid, viewpoints?

RL: Definitely. I learned a valuable lesson from this experience, that there is more than one way of doing things.

TJ: In the book, The Great Cellists, by Margaret Campbell, Stephen Kates describes Leonard Rose as somebody who believed in having his students imitate him. Is this something you experienced?

RL: Yes.

TJ: Did you resent this at the time, or did you find it to be a good learning tool?

RL: I didn’t resent it. Imitation is a good teaching device up to a point, though a student must eventually break from the teacher and find his or her own voice. But it’s not always the teacher’s doing either. Students often fall into the trap of trying to imitate their teacher if the teacher has a very strong personality. I observed this in students of Heifetz and Piatigorsky, and I found myself doing it with Leonard Rose. One day I woke up and realized, “Hey, I’m starting to sound just like Leonard Rose and I wonder if that’s a good thing.” You have to take the concepts from your teacher and work from there to discover your own musical personality.

TJ: Not that there’s anything wrong with sounding like Leonard Rose, of course.

RL: Not at all. We should all be so lucky. Or Piatigorsky, or Heifetz, or whomever.

TJ: Did Leonard Rose teach you his way of playing by telling you to go listen to his recordings, or did he demonstrate in lessons?

RL: He played a great deal in lessons. He not only demonstrated the sonata and concerto literature, but etudes as well. He was trying teach me a very specific kind of bow sound, and a certain kind of vibrato, so there was a lot of imitation. But there was also a lot of detailed technical work, since he was after specific motions with the fingers and hands.

TJ: Such as his ubiquitous “paintbrush technique” for the bow.

RL: Yes. I’m one of those too.

TJ: What are the advantages of the “paintbrush” versus, say, the bow technique of someone like Janos Starker, who uses more of a simple hand motion when bowing?

RL: I’ve always felt that many of Leonard Rose’s students have a very solid bow technique compared to other cellists. The “paintbrush” gives you a lot of flexibility. It produces a more connected sound and gives you more of a sense of control and contact with the string.

TJ: Would you say that Leonard Rose was somebody who planned every detail in his performance, or was he one to go with the spirit of the moment?

RL: No, I think he planned a lot. He didn’t believe in taking chances. He planned and was a very, very hard working musician. He just never stopped practicing and was incredibly conscientious. If he played something in a lesson and happened to miss something, which wasn’t very often, he’d sit there and practice it until he got it right, all the while swearing and screaming at himself. He was real perfectionist.

He sounded so natural to me as a player, but I don’t think it came all that naturally to him. He had to work very, very hard for everything he achieved, which is something I’ve always respected.

TJ: It certainly paid off for him. You have taught throughout your career. You’ve taught at Eastman, and now you’re at USC. Do you have any themes in your own teaching?

RL: Well, of course I use a lot of Leonard Rose’s techniques in my teaching. But if I were to say there’s one thing that I’m most interested in, I would say “sound,” how to produce a beautiful sound. I think that without sound it doesn’t matter how fast or loud you can play. People won’t want to listen to you if you have an ugly sound.

TJ: The definition of what is a beautiful sound is open to a lot of interpretation. It depends on musical context. So when you say this, you’re not implying that a “juicy” vibrato sound is something that we should strive for at all times?

RL: No, but you should be able to vary your sound by controlling your vibrato at a number of speeds and widths so that it is not always the same.

TJ: In other words, there is no single beautiful sound.

RL: Right. There are people who I think have beautiful sounds that have a very fast vibrato, and there are people who have beautiful sounds that have a slow vibrato.

TJ: What else do you emphasize in your teaching?

RL: I’m a very firm believer in using a metronome for practice, because I think we all manage to fool ourselves about how good our rhythm is. At first I have my students play straight like a machine. And then, when they get that right, I complain about their sounding like a machine. That’s the problem with the metronome. If you’re too good with it, then you don’t sound musical. And yet without the rhythmical sense, you’re in big trouble.

Rhythm is one of the really important things in symphony auditions. I would say that rhythm is the thing that does most people in. It can be a simple matter of leaving out a rest, or playing notes a little bit too long so that they don’t make musical sense. It all relates back to rhythm.

TJ: Do you find yourself demonstrating a lot and saying, “Play like this?” Or do you give the student room for their own ideas?

RL: I play little sections of pieces, but I rarely play an entire movement. I’ll play little sections to demonstrate how I think the student should move the bow, what part of the bow should be used, whether near the bridge or at the tip, whether they should have flat hairs or tilt the bow, or what each hand should be doing. I do demonstrate these things, but a lot of the time I do it more to convey a technical approach, rather than for them to play the way I do. As a matter of fact, I very often demonstrate a phrase two or three different ways. I’ll tell a student I like plan A, but if he or she likes plan C, that’s fine with me, but he or she is going to have to convince me. I will ask him or her to work at it those two or three ways anyway. I worry about teachers who demonstrate for an hour.

TJ: There is a lot of competition for relatively few jobs in the music business. Do you discuss this with your students?

RL: I think one thing that has changed in the last twenty years is that a lot of people have realized that it’s not smart to be unrealistic about their possibilities. Only a very few will ever make it as soloists. It’s also very difficult to find a chamber group. Student applications often list one of their aims as to play in a wonderful chamber music group, which is great. But it’s not particularly realistic, because there aren’t too many opportunities. The job that most can look forward to is in an orchestra, which is a wonderful experience.

Orchestras have changed their attitudes towards their players over the years, which can be seen by the fact that many orchestras have their own chamber music series. They’ve realized that it’s important for the players to have a way of expressing themselves a little more individualistically than they possibly can in the orchestra. I work with my students on orchestral repertoire, though not at great length because there isn’t that much time. But I try to tell them realistically what goes on in the orchestra, at least from my vantage point. I think it’s a pretty nice way to spend a life.

TJ: Should one listen to recordings when studying a piece?

RL: No. I can often tell if a student is listening to recordings, because they will play strangely in lessons. I’ll ask them to explain why they are playing a certain way, why they are distorting a certain rhythm, what notes they are playing, or what key are they are in, and they can’t answer me. They’ve listened to a recording from some terrific cellist, and all they’re doing is imitating the recording. Now that can be okay, but when you don’t know what you’re doing, and you’re just playing by ear, I don’t think it’s a help. Not that I didn’t do a certain amount of that myself!

TJ: We all did.

RL: Sure. I remember listening to specific pieces when I was a kid, like the Kodaly Sonata with Janos Starker. I played that record until I wore it out. I also listened to Piatigorsky and Casals recordings. I certainly tried to imitate them. But in a way it’s healthy if you’re imitating a lot of different people, because then you’re experimenting with different kinds of sounds and colors. That’s quite different from listening to cellist A and basing all of your musical judgments on what he or she does. When I’m learning a piece myself, I never listen to a recording. I try to work it out myself by studying the score in addition to the cello part.

TJ: Well, getting back to orchestral playing, what defines a great orchestral player?

RL: I think that people who play chamber music well will most likely be good orchestral players. I look at orchestral playing as a big chamber ensemble. If you’re not tuned into everything that’s going on around you, you’re not going to be a good player. There are tons of people who can play their own parts, but when you play that part you must have an awareness of what’s going on around you in the orchestra.

TJ: In an audition, where somebody is playing by themselves, how would you identify this as one of their traits?

RL: There’s no such thing as an audition that’s going to tell you everything. There’s no way you can know some of these things until you’ve dealt with people in reality, in the section.

TJ: If a player were to make some obvious timbre change or a sudden change in dynamic because they are aware of an oboe entrance that occurs in the piece, for example, would this be something you look for?

RL: Well, that’s awfully subtle. At an audition we don’t have the time to ask somebody what’s happening in the orchestra at each excerpt? This is something I frequently ask my students about when they’re playing a concerto. I’m constantly asking them about what’s going on in the orchestra while they are playing a certain passage. We have started something with the L.A. Philharmonic that I think a lot of orchestras do now with auditions, where we ask people to read chamber music with members of the orchestra. This can give us somewhat of an indication of the kind of an orchestral player each person might be.

TJ: But when you’re judging an audition, you’re listening for rhythm and basic technique.

RL: And for a sense of style of the piece.

TJ: Is it important for an orchestral musician to have artistry, or is that left to the conductor?

RL: If somebody has an incredible personality, sometimes a conductor will say that he’s a terrific player, but he doesn’t think he’s going to fit into the section. Or if somebody has a weird vibrato who might be a fantastic player otherwise, the same thing applies. It’s difficult, because you want to show your personality, and yet, if it’s too flamboyant, it can get you into trouble. It’s hard to get towards that middle of the road.

I remember that George Szell seemed to have a knack for picking “middle of the road” players in auditions. Many said he was more likely to take the person who played everything as close to what he considered “correct,” though it may not have been in the most interesting way imaginable, If the rhythm was right, the sound was right, and if he didn’t feel the musician was going to go off on his own and let his own personal musical ideas take over, then he was interested. He wanted to have control over your musicianship. And it worked. He had a great orchestra.

TJ: Would you say that the average level of an orchestral player has changed in the last twenty years? With all the competition today, you’d think it’d be getting higher and higher.

RL: Yes. There are some wonderful players and the competition is very strong. One often hears about auditions where there are two hundred players vying for one position. But I find that, out of those two hundred players, it’s not difficult to narrow it down to a pretty small number. When we get down to the last ten players, it’s not always easy to say which is the best. In a way it’s the draw of the cards. There are many good players I know who have taken auditions but just haven’t quite clicked. It used to be that the smaller orchestras were depositories of the players who couldn’t make it in the big orchestras, and I guess that’s still true. But the difference now is that there are many players in those smaller orchestras who are very, very much deserving of being in the bigger orchestras. So those communities are lucky. The overall level is certainly higher.

TJ: Many say that musical performances have become too homogenized today. Do you agree with this assessment?

RL: I remember as a student how I thought that people like Piatigorsky, Casals, Leonard Rose, Heifetz and Elman had such distinct personalities. One can think of some orchestras as having distinct personalities too, like the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy. I think that orchestras in particular tend to sound somewhat the same. But that’s up to the conductor, who must have an imaginative set of musical colors within to create something unique. The orchestras are all so good now, they can all play very, very well.

TJ: Is it necessarily a good thing to have a strong personality like Casals? Or does such as personality interfere with the music?

RL: I don’t know. New personalities are always interesting. When someone like Jacqueline du Pre comes along, it’s a revelation. Another is Gidon Kremer, who is certainly a personality. He’s one of those violinists of whom I hear one person say he’s terrible, while the next person will say he’s great!

TJ: Then he must be good.

RL: He is good. Vanilla is not good.

TJ: The following is a list of goals that many have to varying degrees when performing: playing with musicality, playing with personality, clean technique, playing with “taste,” being faithful to the composer, authenticity, and audience pleasure. Let’s say you’re a soloist, what do you care about most? They’re all important of course. But are there some that are a higher priority for you?

RL: The first one would be being heard! It seems to be one of those things that certain conductors or pianists I know don’t take into consideration. How can one put a value on the items in your list, because it’s the composite that we need.

If you take the idea of being faithful to the composer, I think it’s a wonderful idea, in theory at least. Most of the time, when I play something for a composer, I’ll ask him what he wants. But he’ll say, “Let me hear it a couple ways.” Then he’ll often go along with what I’m doing. There are also composers who will say, when you play a piece that they wrote twenty years ago, “I don’t care what you do with that piece. That was a terrible piece anyway!”

I think some of the authenticity gets a little bit out of proportion too. There are markings, for instance, in Beethoven’s music or Bach’s that are obviously wrong. But they’re there in the original, so some claim that’s the way the composer wanted it. That may be true most of the time, but not always. So that’s where good taste comes into play, except that my good taste might not be somebody else’s good taste. Every once in a while I’ll play a movement of a Bach Suite. If there’s a note that’s debatable, in one performance I’ll play one note in the first performance and, in the next performance, I’ll play the other note. And if people want to waste their time arguing about such things, so be it.

TJ: Just tell them they came the wrong night! Do you think there’s such thing as a wrong interpretation?

RL: Oh yes. I definitely think so. If I hear somebody playing Bach the way I think one should play Stravinsky, it’s pretty clear to me that the style doesn’t really fit. I am open to ways of playing Bach that I may not particularly like, though I would consider them valid. But I think there are wrong ways too.

TJ: So how do you think the Bach Suites should sound?

RL: Well, these days that’s a tough question. When I give master classes, I’m stuck with my own background in Bach, which probably relates more to Casals than to anybody else. I approach Bach from a cellistic viewpoint, and don’t consider myself a Baroque expert. When cellists play in a quasi-baroque manner, I don’t know how to deal with it. I don’t play with the change of bow speed and different vibratos that baroque players do. I’ve tried it in the Bach, but I feel uncomfortable so I don’t think I could do it convincingly. I also think that one can go too far in the other direction, for example by playing a Bach Sarabande like a Brahms symphony.

TJ: What if somebody were to play Bach like Casals? Would they be accepted today?

RL: Unfortunately, they probably wouldn’t make it. I’ve thought about this a lot, and I’ve wondered if musicians like Casals or Szigeti could make it in our era. Beside his musical ideas, I don’t think Casals could make it because he didn’t have a big sound. These days, unless you can break glass with your sound, it seems as though the critics aren’t the least bit impressed. I don’t think is a step forward.

TJ: It’s actually kind of sad. Do you have hope for music in the coming century? Classical music seems to be losing its audience.

RL: Everybody’s worried about where the audience is going to come from. There is less and less music in the schools and less music in the homes. People can get everything they want from a CD, and don’t see the need to hear the music live. Orchestras are trying to approach audiences in as many interesting ways as they can, but it’s not easy with all the cutbacks. The day we don’t have great music will be a very sad day for society. We have to do more to bring music especially to young people. And that’s one of the things that the L.A. Philharmonic is trying to do.

TJ: How?

RL: We’re presenting different kinds of concerts. For instance, we have a series of Saturday afternoon concerts to which we invite kids from the inner city. These concerts only last an hour, instead of the usual two and a half hours. This seems to be paying off because I am seeing a lot more young faces in the audience. We’re also planning on doing short chamber music sessions in grade schools. The kids love it and respond wonderfully to the music. Hopefully this will nurture their interest and build our audiences of the future.

2/2/96

Subjects: Interviews