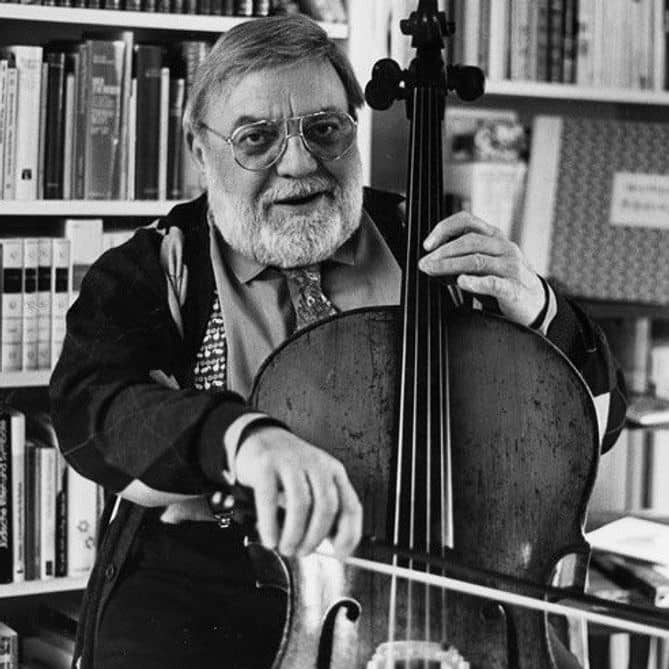

Conversation with Siegfried Palm (May, 1998)

Tim Janof

Interview by Tim Janof

Siegfried Palm has had a distinguished and varied performing career. He was Principal Cellist of orchestras in Lubeck, Hamburg, and Cologne, cellist in the Hamann Quartet, and a member of a trio with Max Rostal and Heinz Schroter. He has given masterclasses worldwide and has served as a jury member at numerous international competitions. He has recorded for several companies and has had works dedicated to him by composers such as Krzystof Penderecki, Yannis Xenakis, Boris Blacher, and Gyorgy Ligeti. He was Director of the State Conservatoire in Cologne, Director of the Deutsche Oper in Berlin, President of the German Composers’ Society, and President of ESTA. In 1969 and 1976 he was awarded the German Gramophone prize, and in 1972 he was awarded the Grand Prix du Disque International.

TJ: You studied with the Italian cellist, Enrico Mainardi.

SP: Yes. He taught me a lot, especially about the bow arm, for which I am very grateful. He also introduced me to the wonderful music of Max Reger, who was one of his favorite composers. I still recall the first time I played for him and his class — a complete disaster. I was 23 years old, and had already been performing as a young soloist. He graciously allowed me to play through the entire Boccherini Concerto without interruption. After I finished, I sat in a painfully long silence as I waited for his comments. After the entire room sat quietly for what seemed like an eternity, Mainardi finally said, “There are lots of ways to play this beautiful piece. But the only way one should NOT play, you did.” Naturally, I was crushed.

TJ: What do you think of the Suzuki method?

SP: I can’t stand it. I see it as more militaristic than musical. When I see a hundred young people playing the same song on violin, I can’t help but imagine that they are actually carrying machine guns. I realize that I am being rather harsh, and it’s a strange thing for the President of ESTA [European String Teacher’s Association] to say for the President of ESTA [European String Teacher’s Association], but I truly believe it. I say this knowing that there are lots of very successful Suzuki teachers in the world.

TJ: Do you encourage students to listen to recordings?

SP: No. If they do, that’s fine, but I prefer that they find their interpretation from the score and from within themselves, rather than by imitating others. I say this even about my own recordings, of which there are many. Believe it or not, except during the editing phase, I’ve never listened to any of my own records.

TJ: Do you feel that the recording age has resulted in the loss of truly unique musical personalities?

SP: I’m not sure that’s true. There are plenty of wonderful young musicians today. I worry more about today’s obsession with technical perfection, and how this can prevent a certain spontaneous emotional element in a performance.

TJ: Do we need any new recordings of musical “warhorses?” For example, do we need another recording of the Dvorak concerto?

SP: No, we don’t need it, but why not? Maybe somebody will have something new to say with these pieces. But just because somebody records a new CD, that does not mean that I have to buy or listen to it. A major problem in the classical music industry is that people have now replaced their vinyl records with CD’s of the Beethoven symphonies and other classics. And, since most people aren’t collectors, the vast majority of the audience has no desire to purchase any more recordings of these same works, and aren’t particularly interested in contemporary works. As a result, the classical music recording industry is in real trouble.

TJ: You are considered by many to have a certain expertise in contemporary music. I realize that “contemporary” is an overly broad term, but let’s go with it for now.

SP: I don’t consider myself to be an expert. How can anybody be an expert on contemporary music when there are thousands of works that have yet to be played or heard? I see contemporary music more as my hobby.

TJ: Contemporary composers have certainly forced us to reconsider how we define “music.” When I watched you bow on your tailpiece in the Penderecki Capriccio, I couldn’t help but ponder whether that was a “musical” moment, or just a very entertaining sound or visual effect.

SP: No, that’s music. Whether or not something is artistic depends on what the composer does with it.

TJ: Do you define music as merely “organized sound?”

SP: No, I don’t think so. You can’t just look at the end result, the music. You must look at the composer’s overall process and techniques, which should also include an understanding of his or her personal and professional background. This is true of any good composer like Penderecki.

TJ: When you play something like the Penderecki Capriccio, do you find meaning in the music?

SP: Sure. The music is full of humor and irony. The main point in this piece is the C major chord, and how he toys with it. But you can’t appreciate this unless you know the music very well.

TJ: So this piece contains inside jokes for musicians, or at least for those who know the score. Do you think that a lot of contemporary music is written more for the appreciation of musicians and composers instead of for the general public?

SP: Absolutely not. Music is written for a variety of reasons and various audiences. Why should it matter for whom a work is written? What matters is your personal experience of the piece.

TJ: Do you think that contemporary music has the same goals as earlier music, like a Beethoven Sonata.

SP: Sure. Tastes have changed and certain rules have changed, but the same artistic goals apply. We still have form, phrases, structural points of arrival, development of certain motives, musical fragments, sounds, moods, and so on. To me there’s no difference between Beethoven’s work and the music of our time. It’s more a question of the quality of the music, and being able to understand the new rules and communicate the music effectively to the audience.

TJ: Given that there is a such a variety of contemporary music, how do you determine whether or not a performance is good? For instance, in your contemporary music master class, how did you decide whether or not the performance was “correct” or not? It’s much easier for most to critique a performance of Bach than of Penderecki?

SP: I think I have a feel for the language, or languages, of contemporary music, which comes from years of experience. The performance must be spirited and full of nuance, just as with any other type of music. I find that most students overlook the finer details of the score, so I call their attention to the composers’ instructions, and share my insights about the inner message of the music. I am fortunate to have worked personally with many of the composers, so I have a certain advantage. I must be on the right track, since I think I am able to communicate the music to the audience. Of course, as with any period in music history, not all contemporary music is great, just as not all classical music is great. But, if a piece is good, and the music community is aware of it, it will endure, while lesser pieces will fade into history.

TJ: Do you find that playing contemporary music gives you insight into earlier music?

SP: Absolutely. It’s unbelievable how your view of earlier music shifts when you play a lot of 20th Century music. Contemporary music forces you to think more analytically, which helps you understand Baroque, Classical, and Romantic music. The trick is to not get too analytical, since, as an artist, one must play from the heart as well.

TJ: Is contemporary music just ahead of its time? Or will the audience ever appreciate it?

SP: I think they will appreciate much of it over time, though there will probably be certain pieces that will never be fully understood. But this isn’t unique to 20th Century music. Look at the late Beethoven Quartets. I doubt that even ten percent of music lovers have the tiniest understanding of them. People don’t like to admit that they might not understand Beethoven, but I am not afraid to say, even after all these years of performing, that I don’t completely comprehend the Opus 131 Quartet.

I question whether it is absolutely necessary that the audience know how a piece is composed. You don’t have to deeply comprehend something in order to enjoy it. For example, you can admire a great painting and yet know very little about the technique of painting. There may always be some works that the audience never understands, just as some late Picasso works may never be fully appreciated. But the pieces shouldn’t be banned from the stage because of this, just as Picasso’s paintings shouldn’t be taken from the museum wall.

TJ: But doesn’t the art of interpretation involve helping the audience understand the piece? If we can’t explain the piece to the audience through our performance, then is there something wrong with the piece?

SP: Some pieces are more difficult to convey to the audience than others. Some require more study and familiarity, but this does not necessarily mean that there is something wrong with the piece. Just as some books require careful and deliberate reading, certain music requires repeated hearings and study as well. We do our best to communicate the piece to the audience. If they get it, we have accomplished something truly wonderful.

I would say this is true of more than just contemporary music. For example, only a fool would claim to completely comprehend the Bach Cello Suites. Any devoted musician spends a lifetime deepening his or her understanding of these wonderful works.

TJ: What are some current trends in contemporary music?

SP: Music continues to change very rapidly. Music was much different even ten years ago, since composers now have much more freedom. I consider the 60’s and 70’s to be a very dark time in composition, since composers had to write in a certain style in order to be taken seriously, instead of being given true artistic freedom. But, having as much freedom as we do today creates other difficulties, since, without a little discipline, it’s too easy to write music that is meandering and confusing. I think a little structure is important in art, since it helps unify a work into a comprehensible whole. Otherwise, why study music at all, and why not just let a monkey write it for you?

Structure is a very important element in art, something that many don’t appreciate. Structure can be as simple as having a guiding concept, or as complicated as adhering to the formal rules of counterpoint, for example. This is a wonderful thing about a composer like Bach, that he can compose great music while still bound by certain conventions.

TJ: Anybody who has taken a course on counterpoint can appreciate this.

SP: What Bach did within his rules is unbelievable. But not all great composers of the past followed the rules of their day. Beethoven, for instance, was a quite a rebel, destroying the conventions of form and harmony in his last twenty or so major works, including breaking his own newly established rules as he went along.

Wagner’s opera, Die Meistersinger, contains some wonderful advice for young composers. In the Third Act, Sachs says to Walter, “Ihr stellt sie selbst, und folgt ihr dann.” [First make your rule, then follow it.] By all means, create your own rules, and don’t worry about what others think. But please follow them, for discipline. Though simple advice, it’s very difficult to follow, though very important.

TJ: Do you judge a work by whether it has a discernible structure?

SP: I don’t like to pass judgment on works of art. I guess my ultimate criteria is whether or not it bores me. When I perform a work, I strive to play it as interestingly as I can, so that the audience is given a fair opportunity to enjoy the piece, instead of quickly dismissing it as boring. I want to do justice to the composer.

TJ: What do you think about a composer like John Cage, who was known to throw dice in certain pieces to determine the notes in a composition? Would you consider his deliberately random process to be his unifying internal structure? Or was it just chaos?

SP: His process was deliberately chaotic in my view, which, though contradictory at first glance, is a very profound and meaningful method of composition. After all, isn’t this a wonderful description of life itself? Ordered chaos? Cage found a new way of feeling music, not just of listening to it. A most fascinating example of this is in his piece, 4’33”, where a pianist sits on stage in silence for just over four and a half minutes. Once you get over the uncomfortable silence, which could be considered as part of the piece actually, you relax and begin to listen to the sounds around you, notice your surroundings, and become conscious of your own thoughts and feelings. Cage was one of the great figures in art, not just in music.

TJ: I have a book, “The Solo Cello” by Dimitry Markevitch, that contains hundreds of works for solo cello, most of which were written in the 20th Century. A cellist’s problem is not that there isn’t enough music out there, it’s just that very few play it or know of it.

SP: There is plenty of music written for cello. The cello has been very popular with composers in the last couple of decades. But I’d bet that the viola, in twenty to thirty years, will be the composers’ instrument of choice. So we should enjoy the attention while we’ve got it.

5/3/98

Subjects: Interviews