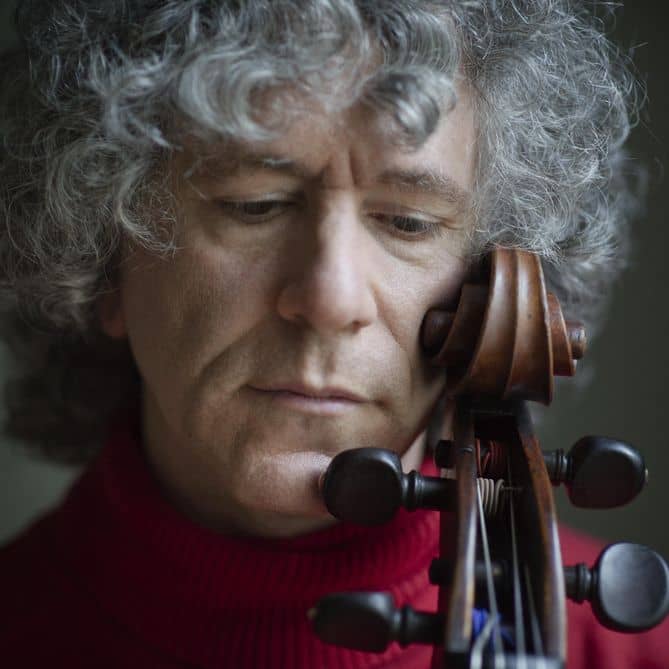

Conversation with Steven Isserlis (May, 1998)

Tim Janof

Interview by Tim Janof

British cellist Steven Isserlis performs regularly with the world’s leading orchestras, including the London Symphony and the Philharmonia, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago and San Francisco Symphonies, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, and Japan’s NHK Orchestra, collaborating with conductors such as Ashkenazy, Eschenbach, Gardiner, Norrington, Slatkin, Solti, and Tilson Thomas. He has enjoyed working with authentic instrument orchestras such as the English Baroque Soloists, the London Classical Players, and l’Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique, and he has also been an inspiration for composer John Tavener, who as a result has written many works for cello. Admired for his expertise in the chamber music repertoire, Isserlis has been responsible for programming and participating in successful chamber music festivals both at London’s Wigmore Hall and at the Salzburg Festival, where in 1997 he was artistic director of a three-concert Mendelssohn cycle. Isserlis’ regular chamber music partners include Joshua Bell, Stephen Hough, Olli Mustonen, and Tabea Zimmermann. He was the subject of a 90-minute profile shown on German television, was featured in the International Emmy Award winning series “Concerto!” with Dudley Moore and Tilson Thomas, and has presented a documentary about the life and late works of Robert Schumann.

TJ: You studied with Jane Cowan. Can you describe her teaching method? I understand that she used a total immersion technique with her students.

SI: That’s true. The last two years I studied with her, I lived in her house in Scotland three times a year, eight weeks each stay.

Her principles were very holistic. For instance, she would have us listen to Goethe’s “Faust” because she thought it would help us play Beethoven better. She also made us read Racine so that we were familiar with the sound of the French language when playing the music of composers like Debussy, Couperin, or Faure. She was always looking for connections between music and the world around us.

She had us analyze the harmonies in the pieces we played, but not in a dry way, which can be intimidating or tedious. It felt as if she were taking us into a new world with each composer, or even each piece. Her approach was very organic.

Everything we did was connected to the music. She never taught technique purely for technique’s sake. She spent a lot of time on technical issues, but it was always presented in the context of helping us to accomplish specific musical goals. We never followed a method mindlessly or played scales just to improve the left hand. Technical discussions always had a musical context.

TJ: In your master class at the Manchester Cello Festival, when discussing the Beethoven A Major and Schubert Arpeggione Sonatas, you often discussed the mood of musical phrases, and asked the students whether a phrase was a “question” or an “answer.” Did this come from Jane Cowan?

SI: She certainly encouraged us to think in terms of speech, stories, or visual images.

TJ: Do you use this approach in Baroque music as well?

SI: Of course. Music means something, no matter what period it comes from.

TJ: Do you think that Bach had meaning in mind when he composed? In one of my past interviews, the cellist felt that we may inject too much meaning in Bach. For instance, he felt that Paul Tortelier had “found” so many layers of meaning in the Sarabande from the C Minor Suite that Bach was somehow lost. After all, Bach probably wrote it in four minutes.

SI: Schumann wrote his cello concerto in four days. I’m told the earth was created in six. Whether he wrote it in four minutes or four years is completely irrelevant. It’s one of the great pieces of music and is incredibly moving.

Certainly Bach’s music had meaning. I don’t mean to say that you can necessarily fit words or specific pictures to his music, but it has meaning, whether or not that meaning can be described in words. Of course, it can’t really be described, because, if it could, we wouldn’t need music!

All music, except perhaps for some experimental contemporary music, has phrasing, so all music has meaning as far as I’m concerned. All the music that I play consists of phrases or clauses in which there are main notes, to which other notes lead, or from which they come away, the same as with words in sentences.

TJ: Do you look for contemporary music that has a sense of musical line?

SI: Yes, I look for music that means something to me. I can only really feel sympathy with music that is somehow organically rooted in the past in this way, no matter how “contemporary” the musical language may be.

TJ: Is there a danger that the music will sound too fussy or too wavy, when one is constantly going towards and away from a main note in phrase after phrase?

SI: Absolutely not. We must not play all notes with equal strength or value, otherwise the music will become monotonous. A lot of people play in a monotone fashion without realizing it because they don’t use the bow to shape the phrases. People would sound very strange if they talked with equal stress on every word — only computers do that. Computers, although they have many great qualities, are not known for the beauty of their musical phrasing.

I remember once comparing a couple of recordings in a lecture. The first featured a famous cellist and pianist performing the slow movement of the Beethoven D major Sonata. It sounded beautiful for a few notes, but then it started to feel incredibly slow and static. Then I put on a recording of Casals and Horszowski playing the same piece. It was twice as slow, but everybody was riveted, because there was a sense of going to and from the main notes of the phrase. I’m not saying you should punch the main note out, I’m just saying that music must have a sense of motion. The music is boring if you don’t shape it. No matter how slow, or how still or calm, music must be phrased.

TJ: You said something interesting in your master class, “One should not do things to the music, music should do things to you.” If you believe this, then what does the act of interpretation involve?

SI: You can’t truly “interpret” a piece until you know it extremely well. You have to know the function of every note, where each one is going, where each fits in its phrase, and how each phrase fits in the overall piece. Once you figure this out, you become like a bird flying over the land, seeing the land as it really is, watching different parts come and go, and seeing what came before and what’s coming next. This is a very different view than what you see if you are on the ground, where you can only see a short distance behind and ahead of you, and where you are overwhelmed by little details instead of the big picture.

Ideally, you get to the stage when you know the piece so well that you can just sit down and listen to what the piece is telling you, which is what I think of as true “interpretation.” Then it will come out differently every time you perform. But this will not happen if you don’t really know where everything fits in the overall picture, which is when you begin to play musical clichés, and you start doing the same things over and over again.

TJ: Do you therefore have a sort of detached view of the music when you play?

SI: I don’t think of it as detached. It’s more as if an actor is being taken over by the character he or she is playing. But, in order for that to happen, the actor has to understand the character thoroughly, to know about every aspect of him or her.

We don’t have to impose our will upon a piece. We need to step out of its way and let it speak through us. Otherwise, we are closing ourselves off from its message.

TJ: You must still make some conscious decisions about how you are going to play a piece.

SI: Of course I do. For instance, I think of Bach’s Third Cello Suite as basically a joyous work. I know that I’m going to play it with dancing rhythms, and that I’m going to feel its sense of celebration. But, having said this, I am careful to check that the music is saying this to me as I’m playing it, which means that I have to listen to it as I play. It’s not that I stubbornly decide that I’m going to smile and play it joyously, no matter what.

I try to let the music tell me how to play, not the other way around. There are times when I’ve consciously decided ahead of time to do a rubato in a particular passage, for example, and I almost always regret it afterwards, since I realize that I let myself get in the way of the music. A rubato has to come from the music, not from me.

People often tell me that I’ve changed the way I play certain pieces over the years. I don’t even realize it’s happening. It’s just that my relationship with the music has changed, as relationships always do.

TJ: What is the process you go through when you are studying a new piece?

SI: I always start at the piano and do some basic analysis. I don’t analyze every chord, but I do study the main themes, how they relate to each other, and how they are developed. Of course, each piece has its own rules and must be analyzed in a different way. I’m not a trained analyst, but I have to do this in order to understand what the piece means to me. After this analysis, and after six or seven performances, I sometimes start to feel at home with a work.

TJ: You mentioned Bach. Do you have more “romantic” or more “authentic” leanings in your approach when you play the cello suites?

SI: I think that both approaches, and anything in between, can be good or bad, but they’re not mutually exclusive. A truly “authentic” approach will be romantic, in a sense, and we are all trying to be “authentic” in our different ways. What matters is whether you are truly responding to Bach’s music, or whether you are just following rules or clichés set down by a third party.

If you listen to two great Bach players like, say, Casals and Bylsma, their spirit has a lot in common. If they were actors playing “King Lear,” for instance, Bylsma would be using something closer to what we believe to be the pronunciation used in Shakespeare’s time, and performing on an Elizabethan set. Casals would be using modern pronunciation in a more modern setting. But what matters ultimately is the emotional power and the tragedy that they both could convey.

I like to play with original instrument orchestras, but I’ve always used my own cello, with some difference in set-up, depending on the period of the music. I’ve never performed the Bach Suites on a baroque cello, but I’ve listened to lots of original instrument performances of all kinds of music. Occasionally I practice with a baroque or classical bow.

I use the Anna Magdalena Bach manuscript almost exclusively, though I like to look at the other early ones. I decide what I think might be mistakes, what is meant by the indicated bowings, and which patterns are meant to continue, and which aren’t. I also like to bring out the different characters of the dances and their different meters, with their different metric accents.

TJ: So you bring out the second beat in sarabandes, for instance?

SI: I also bring out the first beat. I think this is a common misconception, that only the second beat must be emphasized in sarabandes. I find that remembering the relative importance of each beat in the different dances can help everything fall into place, especially in a movement such as the D Major Allemande, which has such slow beats.

TJ: What do you mean by “slow”? Do you play it so slowly that each thirty-second note is given special meaning?

SI: With so many notes, the beat has to be slow, but we mustn’t lose sight of the fact that the piece has four beats per measure, not eight. When you think of it this way, the relationship between the many little notes and the main beats becomes more important than individual thirty-second notes.

TJ: Do you view the many little notes in this Allemande as ornamentation?

SI: I see them as expressive ornamentation and as a connection between the chords of the main beats. I remember when Jane Cowan’s daughter, Lucy, a violinist, while discussing the Allemande of the G Major Suite, drew a picture of telephone poles on my music, with wires connecting them together. The poles were the main beats and their associated chords, and the wires were the little notes that connect the chords together. I find this analogy to be quite helpful.

TJ: What note do you start your trills on in Bach?

SI: It depends on the preceding note, but generally I start on the upper note, of course. The length of the vorschlag, or appoggiatura, depends on how much you want to feel the tension between dissonance and resolution.

TJ: How do you feel about using vibrato in Bach?

SI: I think of it as an expressive ornament, like a trill. When I hear automatic vibrato, I think it sounds wrong. Vibrato should be a living aspect of phrasing and interpretation, not a mindless one.

My use of vibrato is not that conscious, so I don’t sit down and figure out precisely which kind of vibrato I’m going to use throughout a piece. I let the music tell me. For instance, in Bach, I use less vibrato simply because the piece demands less.

I like what Leopold Mozart said about vibrato, though it may not always apply to later music, that the purpose of vibrato is to make each note resonate like an open string. There are people who play without vibrato and who don’t make the string vibrate with their bow, which usually sounds just as hideous as those who use too much vibrato. The string has to vibrate freely in some way, with or without vibrato.

TJ: Do you play all repeats in Bach?

SI: Yes, I do them all, just because it feels right. I think all repeats were intended by Bach.

TJ: Do you try to do something different when you repeat?

SI: I try not to “try” anything with the music. I try to let the music try something with me. A repeat always feels different anyway. That’s why taking a repeat always feels so right to me.

TJ: Do you ever add ornaments when you play Bach?

SI: Sure, if it occurs to me and feels right. But it must not degenerate into showing off. Once I heard the Sarabande from the Third Suite played with so many added ornaments that I found myself thinking about the ornaments instead of the Sarabande. Nothing must distract from the spirit of the music.

I certainly add ornaments when they seem to have been left out by mistake. For instance, in the Allemande of the First Suite, there is a fifth (E and B) where a trill is not indicated in the manuscript. This is clearly a trill, in my view. But I believe that one is free to add ornaments as and when they feel appropriate in the Suites.

TJ: Let’s skip a couple of centuries and talk about “Schelomo,” by Ernst Bloch. I found your approach in this piece to be truly unique, especially in how sparingly you used vibrato. Most performers unleash a lush vibrato throughout this work. Where did you get the idea to use vibrato so sparingly?

SI: I don’t know. I only use vibrato when it’s expressive, and I often think it’s more expressive not to vibrate in “Schelomo.” If you really want to feel the pain of an interval or chord, it’s often better to fight against the impulse to vibrate, rather than lapsing into anything luscious.

I think people indulge themselves too much in this piece, instead of just following Bloch’s rather explicit markings. Although “Schelomo” is a rhapsody, there are still very distinct sections, which Bloch clearly described in his program notes. If you indulge yourself completely, bending the rhythm and tempo all over the place, as is often done, you will lose the story that is being told. One section will blend into another, instead of remaining distinct. This is a wonderful piece, and I trust that Bloch knew what he wanted, unlike some composers, whose markings have to be taken with a grain of salt — not ignored, of course, but carefully interpreted.

TJ: As I recall, Zara Nelsova, who played “Schelomo” with Ernst Bloch conducting, used a generous amount of vibrato. It is likely that she learned first hand what Bloch was looking for. Could one therefore say that her performance was probably more “authentic” than yours?

SI: It’s hard to say. I’m sure Bloch loved the way that Zara played it – she plays wonderfully. But then we know that he also performed the work with many other cellists, including Piatigorsky. I’m sure they played it completely differently, but presumably Bloch was convinced by them too.

Of course, I’ll always listen to the composer’s interpretation of a piece, but I don’t feel bound by it. For instance, in the Barber concerto, the score does not say to play slower when you reach the second theme in the last movement, and yet, in Zara Nelsova’s recording with Barber conducting, she plays it much slower. She makes it sound great, but for me, it felt more natural to do what was in the score, what Barber the composer wrote, not what Barber the performer conducted.

TJ: Could it be that you are actually violating Barber’s wishes, since, upon hearing his work performed, he decided to have the theme played slower? Don’t you think he clearly demonstrated what he wanted?

SI: Not necessarily. I’m sure that he approved of the way she played it, just as I’m sure that Elgar was won over by Beatrice Harrison’s playing of his concerto. But that doesn’t make the performance definitive, or mean that we should just imitate these performances. Our relationship must be with the music itself, not with a recording.

TJ: There are countless examples of other composers, including Shostakovich and Stravinsky, who didn’t follow their own scores when they performed. Doesn’t this make you question your apparent slavery to the score? If composers don’t follow their own instructions, why should you?

SI: The composer-as-performer is bound by the same limitations we all are. The orchestra, his conducting technique, his mood, or a bad meal can affect the way he or she plays or conducts. But the score is what the piece is, not a performance. The composer is just another very well-qualified performer.

I don’t think of myself as a slave to the score. There are certainly many instances when the composer’s markings are extremely fallible — metronome markings, for example. Faure is a composer whose metronome marks are problematic, as he himself admitted; there’s a letter in which he boasts that got the speed right — for once! One must always try what is written first, then decide whether or not to follow certain markings. At least you have to try to understand why the composer put them there in the first place.

As another example, I play Bloch’s “Pieces from Jewish Life” in reverse order, and I change some of the dynamics, because I feel that the overall work becomes more powerful, and expresses the architecture and meaning of the pieces more effectively. I just hope that Bloch would have approved. I’ll have to wait until the next life to find out.

Some composers give specific instructions and some don’t. Debussy is absolutely specific, so I try to follow his instructions very carefully, but composers like John Tavener are not. When I collaborated with him, I’d ask, “Shouldn’t this be a bit faster?”

He’d reply, “Yes, maybe a little faster.”

“Or perhaps it should be a bit slower.”

“Oh, yes, maybe a little slower.”

So, you have to assess carefully when to take the composer’s markings literally, and when just to use them as a starting point, or as a signpost.

TJ: Is there room for spontaneity in a piece like the Debussy Sonata? Do you give yourself room to play a dash instead of a dot over a note?

SI: Sure. Don’t fall prey to the common misconception that thinking about a piece means that you can’t be spontaneous. It’s just that you can’t understand a piece without thinking about it.

I think you can be true to the score and still have much room for spontaneity. If you get to know the score intimately, things will happen naturally. Spontaneity must come from the piece, otherwise I think the musician is distorting the work.

For example, in the Debussy Sonata, you first have to understand why he wrote the dot instead of the dash. Of course there are many ways to interpret these symbols, but at least you have to understand why he may have wanted the note separated. If an interpreter really thinks about a composer’s markings, he or she will come up with an entirely different interpretation from anybody else’s. It’s only when you don’t think for yourself that you end up sounding like other people. Beware, though, the consequence of this exercise may be that you no longer want to change the dot to a dash!

TJ: Do you feel that you have more freedom playing Bach than Debussy, since Bach was not as detailed in his instructions?

SI: I feel like I have a little less help, particularly dynamically, but I still think he implied a lot. His notes clearly rise and fall in phrases, which I try to follow musically. Though he wrote few actual dynamic markings, I believe his dynamics are indicated in the notes.

I object to musicians who superimpose a huge ending on a piece just to get lots of applause when it actually ends gently or with a falling line.

TJ: Do you listen to recordings when you study a piece?

SI: I listen to very few cello recordings these days. As they say, “Why go through a vicar when you can talk to God yourself?” Of course, I encourage everybody to buy Steven Isserlis’ recordings, just don’t listen to them. That way we’re both happy.

TJ: It seems like you have both an intellectual and inspirational approach when you play a piece. How did you find this delicate balance between your head and heart?

SI: I don’t consider the head and heart to be opposing forces within myself. They are in league with each other. The more you get to know a composer, or a piece, the more you can relax and be yourself with them, just as you can relax with trusted friends. Likewise, until you really know a score, which involves a lot of thought, you can’t relax with a piece and make it a part of yourself. You have to become friends with it.

I don’t dryly think “first subject second subject” as I play. I think about the first subject and try to understand its character, color, or mood. Then I think about the second subject in the same way, and also how it relates to the first subject. Understanding the architecture of a piece is just the first step in befriending a work.

TJ: Do you think that there’s such a thing as a wrong interpretation?

SI: Yes. When a composer’s wishes are ignored or manipulated, or when somebody distorts a piece for their own purposes, I think it’s wrong.

TJ: In reviews of your live concerto performances, I often read that you can’t be heard. They usually blame it on your gut strings.

SI: I use gut strings because I like them, and because they are an essential part of my musical voice. When my friend Thomas Demenga played on gut strings, everybody complained about not hearing him either. So he changed his strings to steel, but didn’t tell anybody. Nobody noticed the difference, and they still complained about not hearing him. After awhile, he started telling people he was using steel strings, and suddenly the complaints stopped.

When I met Lynn Harrell, hardly the softest of cellists, he was very encouraging about gut strings. He told me that he knows that gut strings are just as loud as steel. So don’t blame the strings, blame me! But I do think it’s hard for a single cello to be heard over an orchestra.

I also think that people need to listen more carefully. When I’m playing a concerto, I’m concerned that the principal voice should come through clearly, on whichever instrument has the main voice at the time, like chamber music on a large scale.

In the Dvorak Concerto, for example, the solo cello of course has to be heroic, but there are lots of important flute and clarinet solos that need to be heard as well. It’s almost a triple concerto for cello, clarinet, and flute. I also think of the Dvorak Concerto as a symphonic work with a very big cello part, so I don’t want to be thrust in front, with the orchestra treated as a mere accompaniment. Although there is a lot of heroic writing for the cello, there is a lot of gentle nostalgia throughout the work, and a strong sense of farewell in the coda of the last movement. If one is overly concerned with projection, one loses the intimacy and the inward feelings. Perhaps the audience hears every note of the cello, but they don’t hear the music.

Similarly, if I’m playing a Haydn Concerto, for instance, no matter how large the venue is, I mustn’t force anything, or I’ll lose the elegance and charm that is so essential to the music. What I try to do is bring the listener towards me, towards the music. I’m sure that I don’t always succeed, but I try.

TJ: Do you ever have imagery in mind when you perform, like when you play Beethoven, for instance?

SI: It depends on the composer and the piece. It’s often difficult to conjure up specific images in Beethoven. I think of the story of the Passion when I play Bach’s Fifth Suite, and the Resurrection when I play the Sixth, at least in the beginning, which sounds like bells pealing. There is very strong imagery in Janacek’s Pohadka, of course. And I like to think of the sea at the beginning of Brahms F major sonata, with those ceaseless rhythmic waves in the piano part.

TJ: How about in Debussy?

SI: There’s definitely some sort of story being told, but I don’t think the audience should know about it, because Debussy didn’t want that. When somebody wanted to put a printed version of the story in the program for the first performance, Debussy was furious. He wanted the audience members to make up their own stories.

Music should be interactive. There are an infinite number of ways for both performers and listeners to understand any piece. My job is to convey as clearly and as honestly as I can the music as I see or hear it. Then I just hope that the message comes across.

5/2/98

Subjects: Interviews