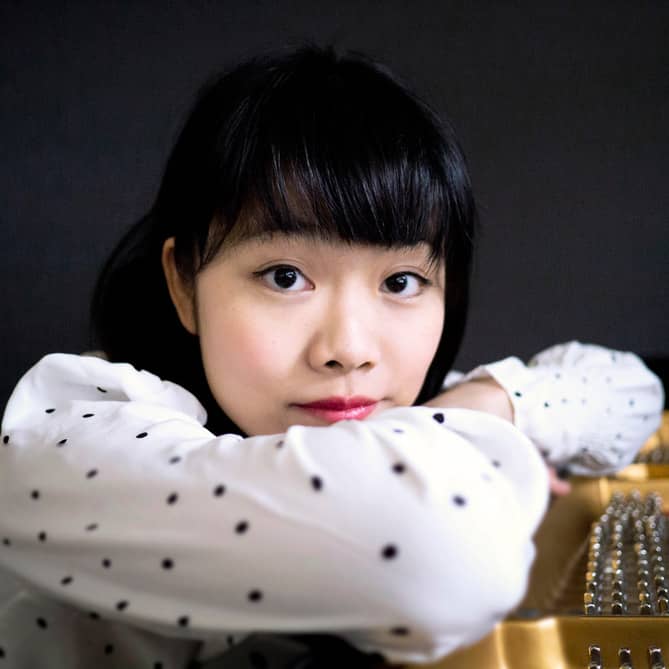

Interview with Tiffany Poon, Founder of Together with Classical

Paul Katz

CelloBello is very excited to begin a new partnership with Together with Classical, an organization that strives to empower people of diverse musical backgrounds to learn and share their experiences with classical music, through online community engagement, grant-giving, interviews and educational videos. Today we begin with CelloBello founder Paul Katz interviewing the founder of Together with Classical, pianist Tiffany Poon. Be sure to check out the Together with Classical Blog for Tiffany’s interview of Paul Katz!

PK: Tiffany is the founder of Together with Classical. She’s a pianist with a concert career. She’s done a lot of playing with cellists, particularly with Jan Vogler but also Guy Johnston and Harriet Krijgh. So, welcome to CelloBello! Let’s start by you telling us a little bit about yourself: where were you born, where was your early music education, and how did you come to be a pianist?

Tiffany: Thank you for having me! I’ve heard a lot about you and CelloBello, and I’m glad to be connected and to be interviewed.

So, I was born in Hong Kong, and I started being interested in piano and music through a toy piano. I recently found out through my mom that I actually had two toy pianos. I was so obsessed with the original one, which just had four keys and was very colorful. It eventually started to get rusty because I used it so much, so my mom decided to get a second toy piano just in case that one fell apart.

So that was a big part of my beginning in music. Eventually, I think my parents just thought, if she’s so obsessed with just four keys, what would happen when there are 84 more? I think I just liked to push buttons and play with my fingers. I even liked to tap on my dad’s computer keyboard. Something about movement with my fingers caught my interest early, so I started playing piano when I was four or five years old.

PK: I’m glad you chose piano rather than computer.

Tiffany: Ironically though, now I do a lot of computer stuff too, so I don’t know, I guess keyboards are just always in my world somehow.

PK: What’s an early musical education like in Hong Kong?

Tiffany: I don’t think I am an exemplary person for this because I took so many private lessons with so many different teachers that I’ve lost count. I kept switching around, and I just wasn’t fully satisfied with any one single teacher for a really long time. I just kept switching around to see who would fit best. Then at some point when I was seven I applied to the Juilliard Pre-College Program.

I made the audition tape when I was seven, got the audition when I was eight and then I was accepted into the program. However I failed the English proficiency exam because I couldn’t answer the question, what’s the color of the carpet? So I had to defer for a year to learn English in Hong Kong, where I attended an international school. The next year, now nine years old, I came back to New York with my mom and I attended Pre-College for the next eight years.

PK: I see. Wow. So then when you left the Pre-College program, you went into the Columbia Juilliard Joint Program?

Tiffany: I actually did the Exchange Program. I’m going to disappoint a lot of people because people tend to think that I graduated and studied at Juilliard, which is kind of true. I did do my Master’s there, but I wanted to spend all four years at Columbia. I was very lucky to have a full ride, so I took that opportunity to study something else.

I went in thinking I would study English because I liked to read when I was in high school, but then I hated dissecting sentences apart. Then I took a class during my first semester, the very first class of college, called Philosophy of Art, and that really opened my mind up. That’s when I realized that it was not only interesting for myself, but it was very beneficial for me as a musician to study philosophy. Of course during this time I also took lessons with Joseph Kalichstein (may he rest in peace) and Manny Ax, while I was studying full-time at Columbia.

So through the Exchange program, that’s what I was doing.

PK: So how do you think your academic interests and the studying that you did at Columbia have impacted you as a musician?

Tiffany: I think it trained me to think in multiple perspectives. I loved that I was constantly being asked for essays. We had to constantly argue against ourselves or argue in favor of another philosopher’s ideas. I think it’s very similar to playing music where you’re bringing someone else’s ideas to an audience. You’re still trying to make a composer’s music sound as convincing and provocative and emotional or impactful for the audience, and I think it’s quite similar to constantly thinking in someone else’s perspective.

PK: Putting yourself in someone else’s shoes, in the composer’s shoes.

Tiffany: And I think it’s also not just one, you have this constant dialectic. I think that’s also my favorite thing, going back and forth. Sometimes overthinking can become an issue, but then I think it’s through that dialectic of questioning back and forth that we engage with the music. Whether it’s about a philosophical idea or maybe it’s about a phrase of music, the question is always, how do you express an idea convincingly? It’s very similar, I think.

PK: This is a joke, but also a question: do you use your debating skills when you’re collaborating with other musicians?

Tiffany: Oh boy, no, haha. I think I am very lucky to be collaborating with people who have more experience than I do. So I tend to try to take the backseat, not say too many words and just try to learn from their experience and from someone else’s interpretation. Once in a while I might have a bit of tug and pull situation, but it all works out fine.

PK: I think tug and pull is wonderful when it’s collaborative and you’re learning from each other, right? It’s probably what you were doing in your philosophy class?

Tiffany: Yes. I remember there were assignments where you had to fit everything in just one page and you couldn’t cheat and just put the text in five point font. So you also had to think very carefully and be judicious about what words you used. It was very good training and I was very lucky and grateful for that for years.

PK: So that’s a fascinating background. Now, tell me a little bit about your concertizing career. I think you’ve been in a number of competitions, and is that what led to your solo concerts? How has your career developed?

Tiffany: It’s a good question. I think it’s an ongoing question. I was very lucky that I met some people who were enthusiastic to accept me under their wing. And so I was part of a Young Artist Foundation. I got to play some debut recitals in prominent festivals like Gilmore Festival, Klavierfestival Ruhr in Germany, and on the Tonhalle-Orchester Zurich Series.

I have a lot of different experiences debuting, but my career is constantly evolving. Recently there was a release of a CD that I collaborated on with other musicians, including Jan, to play Dvorak’s Dumky trio. And I got to record also a solo track Humoresque. So I’m very excited for the recording chapter of my career as well. There are lots of things going on.

PK: Why don’t we talk about your cello collaborations. I’m asking this question because it might be helpful to cellists. When you’re playing and a cellist is taking a freedom, taking a rubato, what is it that you need from the cellist so that you can be with them? Do you think about body language?

Tiffany: You know, that’s a good question because I’m not sure that I know exactly if there is any one thing. So for example, I played with cellist Harriet Krijgh recently and it was very surreal how we don’t know each other yet somehow our energy just synced. And I could sense that I felt comfortable 95% of the time. I knew when she was going to take time, I could kind of hear it and she could also take into account my rubato and it somehow clicked. We didn’t talk about it.

We barely discussed any sections for rehearsals, but it was very, very organic. So I’m not sure, I think sometimes it’s probably about synchronization. If you’re moving your bow and your body movement, and they somehow have to be in sync. Any physical hesitation in the body language is what makes it hard.

PK: What I hear you saying is that there is a visual aspect to playing together. It may not be a very conscious one, but there was something about her bow and her body. So have you had any experiences where it’s almost impossible or very uncomfortable?

Tiffany: I’m not sure. I think I’ve just been very lucky that I got thrown into playing in Moritzburg where everyone’s playing at such a high level, that I don’t remember having such anxiety inducing moments of rubato. I think it’s also a bit of the pianist’s responsibility to not hold onto our own little bubble so much and just give trust to the collaborator.

I think it’s something to do with mutual trust in the energy so that you can really listen and then also give and take in the same way.

PK: Mutual is exactly the right word, because the cellist also shouldn’t be holding onto their own little bubble. String players, we’re one note instruments and we sit there and we learn these sonatas in isolation. Especially kids that haven’t had a lot of chance to play with piano, the day comes that they get together with piano and too often they’re not listening and not responsive. At that early moment, an inexperienced player needs to listen more to their partner than to themself, you know? Ideally, we should expand our ears so that we take in both together, interact with each other, and hear the work as an entity.

Tiffany: Yes, that’s true. Now that I think about it, maybe I don’t even hear myself so much when I play with someone else. I’m constantly paying attention to their part. And that’s why when I rehearse, especially when it comes to duos, but pretty much all chamber music, I try to rehearse with all kinds of recordings just to have that flexibility in preparation.

PK: So let’s talk a little bit about Together with Classical. What was it that motivated you to begin this? What are your goals? What are your dreams, in terms of Together with Classical?

Tiffany: Together with Classical started during the pandemic. I was doing fundraiser concerts on my YouTube channel for frontline workers, and we raised quite a bit of money. I say we because I think all of the credit goes to the community, who just were so generous. From where I was, stuck in my apartment living near a hospital, I thought I might as well do something.

I felt it was very unfair for me to have the support of my audience online and not have to worry about paying my bills at a time when others were really suffering. I heard the sirens constantly and it just didn’t make me feel very comfortable to be so lucky during that time, so I tried to give back.

Because the fundraisers for frontline workers seemed to do so well, I decided to also give back to my music community. I was also thinking about my interactions with my audience and how there’s this stigma that classical music people are very much separated. There are the amateurs that tend to be very apologetic or shy about their attitude towards music. And then sometimes the professionals and the great artists just seem so perfect and unattainable. I don’t really know how to connect with that type of hierarchical relationship to classical music. I just want everyone to exist in one place and be friendly.

Clearly there are professionals who are very open to connecting with others and are very human and relatable. That’s my hope for Together with Classical, that it will create a community that is really inclusive and inviting to everyone who loves classical music. Whether they are doctors, scientists, students trying to get into classical music, or world class musicians like yourself or Midori or Jan—it’s about trying to have that inviting environment and community.

So we were giving back through fundraisers for other organizations who are giving funds to musicians in need. We then also started our own grants for musicians or music students to support instrument upgrades or lessons or to fund music projects.

So we did two rounds of that, and the last round was in collaboration with Henle which was very nice and generous of them.

Now we’re in an educational phase where we’re trying to start the first animated education series on YouTube about classical music called Classical Being. We’re in the fundraising stages, and also organizing internally for this project. We’re hoping the first episodes will come out in October.

PK: Talk a little bit about Classical Being. How do you envision that?

Tiffany: We’re not trying to replace an actual music education, but we’re trying to introduce classical music to a broader audience using little short animations or cartoons about various topics, to then introduce the content in a way that’s very engaging for people of all ages. It’s just about trying to get them interested in little aspects of classical music in a way that is hopefully less intimidating or confusing—just to kind of give them little nuggets of information, and try to widen the audience for classical music.

PK: So it’s sort of educationally oriented, but for the listener, for the general public.

Tiffany: I think it’s trying to reach anyone. Of course there’s some people who might know already a lot about a certain topic, but I think it’s trying to reach a larger audience on all kinds of topics from history to composers to different instruments, or maybe even just talking about how do you go to a classical concert?

PK: Are you producing these yourself?

Tiffany: Oh gosh, no. We have a team of educators, and they help to come up with the scripts for the lessons, and then we hire animators to then bring those lessons to life.

PK: Wow, that’s exciting. That sounds amazing. Can you give me an example of a few topics?

Tiffany: Our first episode is called “what is classical music?” It’s an overview of the different eras just to get people thinking about how we usually categorize classical music. What makes them different? How do they I sound? Something that is kind of introductory. Another episode topic might be ‘what is the history of classical guitar?” Maybe we’ll do something about cello! I don’t know.

PK: I’m wishing you great success with this. I think it’s fantastic, and it’s really needed. There are so many people that think that they don’t know enough to enjoy classical music, but It’s not really a matter of knowing, it’s a matter of exposure, I think. And your animations will also help reduce an unfortunate elitist image. The opportunity to experience classical music (I believe in live concerts), the shedding of our elitist image, and our reaching out, as we and many others are doing, will help new audiences feel welcome and comfortable.

Tiffany: I think it’s also just that a lot of times classical music might be geographically more popular or more accessible and available in certain countries, And so we’re trying to kind of reach those other areas as well and broaden the exposure to classical music.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

Subjects: Artistic Vision, Interviews