Ready, Set, Stop! A Different Kind of Preparation

Selma Gokcen

It is what you have been doing in preparation that counts when it comes to making movements. -F.M. Alexander

In all my years of musical training I was shown many important aspects of cello technique, which included movements associated with the bow and left hand—what I call the ‘ready-set-go’ school. Your teacher explains, you listen and watch, and then you do… and then you do some more of this work in the practice room until the movements are learned.

I only became aware of the profound importance of another, entirely different form of preparation when I began training as an Alexander Technique teacher. The beauty and simplicity of it took my breath away. Many years later now, as I work with students, some of them express the same incredulity. How can the energies within the body travel upwards, up along the spine, as it descends in space? What is this extraordinary power of Up against gravity and why don’t we musicians know about this first, before all else? It makes the work of the limbs—both the arms and legs—seem effortless. When the spinal column is lengthening in movement, we are in the lap of grace itself.

It is simple but not easy, as my teachers always warned me. And how right they were! The principle itself is simple: when we allow the neck to release tension, the head will move delicately forward and ‘up’ of the spine, which causes the lengthening of the spine and the widening of the back. Learning to live its essence is the hardest thing I have ever come up against.

Alexander called his discovery of this principle the Primary Control of the use of the self. He made this discovery gradually and incrementally. He first noticed that he was pulling his head back and down to initiate a movement. It wasn’t obvious and it took many attempts at self-observation, comparing ordinary speaking with his more intensive stage voice, before he realized that his habit was with him all the time, whether on stage or off. For performers his work is revelatory. If a problem appears on stage, can it just be stage fright? Could the roots of the habit be much deeper than we know, manifesting at their maximum when we are under the most pressure, but there all the same in our everyday life—just not as noticeable?

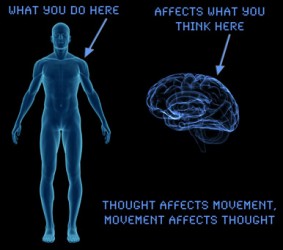

The preparation that most of us make to move is almost universal nowadays. As the thought of moving comes to us, we are unaware of how we prepare by tightening the neck and pulling the head back and down into the spine. The freedom and grace of the spinal column is instantly compromised. It happens wordlessly, soundlessly, thousands of times a day. A thought triggers a habit.

So how to tackle this beast called habit which has us in its soundless grip? There are no direct ways, as Alexander discovered. We can neither command ourselves nor try to do something different. Our habits will get the better of us simply because those old movement patterns are stored in the deep brain structures; the patterns have become automatic, activated in milliseconds. Thought = action.

That’s where the new way of working comes in. In the beginning, my teachers did not allow me to entertain the idea of moving nor to prepare for it. This function of the nervous system is called inhibition—non-doing or stopping—allowing the nervous system to come into a state of quiet, not intending or wanting to do anything. For speed queens like me, this was nearly impossible. But that is what true learning is: going for the impossible, nothing less.

It takes years of work to be able to stop and to direct the flow of energy differently within the body before the inner movement begins to determine the outer movement. We can either compress our spines to descend into a chair or go up along the spine to do the same, allowing for that graceful extension of the spinal column. In fact, with every move we make, we can either pull down on ourselves or go up. One of my Alexander teachers, an erstwhile cellist, used to call it the ‘pitch of the body.’ Her expression gave new meaning to the words ‘in tune with Nature.’

Subjects: Playing Healthy