The Spine: Our Very Own Superhighway

Selma Gokcen

I only learned about the importance of the spinal column to cello playing as I was introduced more deeply into the Alexander Technique. Of course I knew the superficial facts about the spine and especially how vital it is to the health of the nervous system. But its particular relevance to cellists was not brought home until I began training in the work of teaching the Technique.

Here are a few interesting facts about the spine to start off 1:

- The spinal cord is surrounded by rings of bone called vertebrae.

- Both are covered by a protective membrane.

- Together, the vertebrae and the membrane make up the spinal column, or backbone.

- The backbone, which protects the spinal cord, starts at the base of the skull and ends just above the hips.

- The spinal cord is about 18 inches long. It extends from the base of the brain, down the middle of the back, to just below the last rib in the waist area.

- The main job of the spinal cord is to be the communication system between the brain and the body by carrying messages that allow people to move and feel sensation.

- Spinal nerve cells, called neurons, carry messages to and from the spinal cord, via spinal nerves.

- Messages carried by the spinal nerves leave the spinal cord through openings in the vertebrae.

- Spinal nerve roots branch off the spinal cord in pairs, one going to each side of the body.

- Every nerve has a special job for movement and feeling. They tell the muscles in the arms, hands, fingers, legs, toes, chest and other parts of the body how and when to move. They also carry messages back to the brain about sensations, such as pain, temperature and touch.

What the above facts do not tell us is what happens in day-to- day life to us as cellists when, unknowingly, we compress our spine in practicing and playing our instrument. How and why does this happen?

The S-curves of the spine (there are four, some say five if you count the coccyx), as well as its discs, are springy, to allow us to absorb the force of gravity as we move about in space, and they also function as shock absorbers as we walk along the ground. But this spring in the spine only occurs if the weight of the head is balancing properly on top of the spine, which allows a natural lengthening of the spine to occur. The head and neck are key to this process, and yet this head to spine relationship is so rarely noticed, let alone taught, in the cello studio.

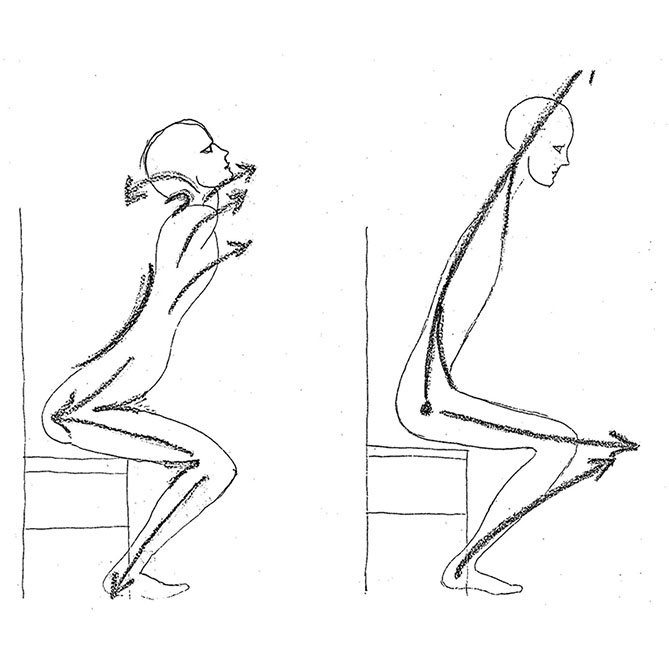

Sadly, cellists tend to either pull the head forward and down, or back and down, onto the spine, restricting the vital impulses of the spine and cutting the energy flow to the arms and fingers. This pulling out of balance of the head is accompanied by a collapse of the spine; the entire body loses its tuning, its axis, its means of functioning.

On another level the fine energies of the spine are life-giving. They are what enable the rhythmic vitality, the tonal resonance, the vital communicative power of the player, the flow of musical expression. If all the gestures a cellist makes—right and left hand—arise from a lengthening spine, they awaken a different sound at the instrument, a deeper, authentic power. This has been my experience of the Alexander Technique, as I watch my students transform and blossom into fluent and expressive players. Those who ‘have a back and a spine’; can be distinguished from those who don’t. And it’s not what you get in a gym. It is a result of very fine, subtle work in undoing those habits of compression and tightening which may have been acquired unknowingly, sometimes many years ago.

When my students, well into the Alexander work, ask me why such important information is not better known and not widely taught, I don’t know what to say. Perhaps we are just beginning to recognize something that we are losing in the new world of the 21st century.

_________________________

1 http://www.spinalinjury101.org/details/anatomy

Subjects: Playing Healthy