What “Posture” Looks Like on the Inside

Blogmaster

The perfect posture can feel like an illusive goal. It has the power to empower the performer and fuel expression or it can limit every aspect of a performance. What is “posture” and how can it be perfect? The problem is that posture is often assessed by one’s appearance as they sit and play. This is far from a perfect or repeatable science. I offer you another way to understand and assess posture, and that is from inside the body. From the inside, we can utilize the body’s amazing design for being upright and for movement.

Forget Posture

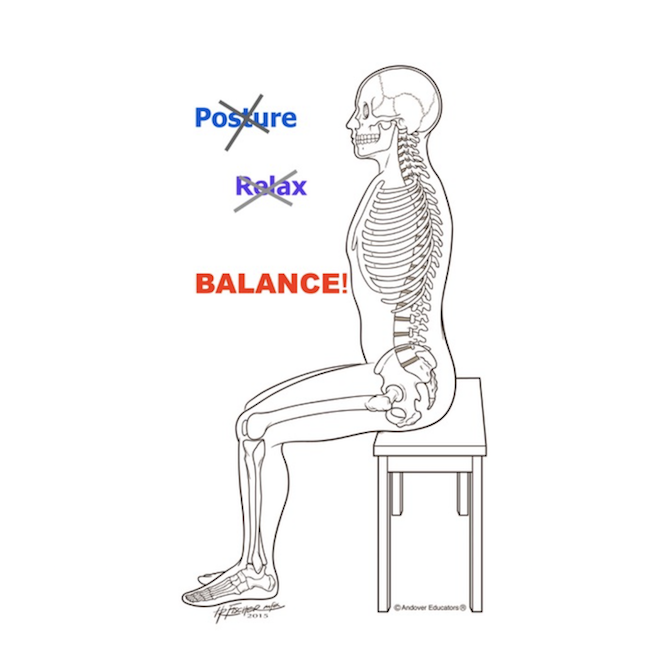

The first thing I want to do is remove ‘posture’ for your musical vocabulary. Why you ask? According to dictionary.com, the definition of posture is “the position of the limbs or the carriage of the body as a whole.” Playing the cello or any instrument is a fluid, dynamic choreography of movement. How do you imagine being in a ‘position’ influences playing movement and the performance? So from here on out, let’s replace the term ‘Posture’ with the word ‘Balance.’ As you will see, balance can be identified anatomically as the relationship between specific places in the body. The beauty of balance is we can learn to perceive it and return to it, even in the heat of performance.

Close your eyes and imagine yourself sitting in balance with your cello. Deliver your hand and bow to the instrument to play. How is this different from the way you currently play? What do you notice about the quality of your bow strokes and the movement of your fingers on the fingerboard?

What does balance look like?

Balance looks comfortable, buoyant, and grounded. It distributes the effort of being upright throughout the body. In balance, breathing is easy and the arms can move easily in many directions.

We are going to map four places in the body that align in balance.

- Sitting Bones

- Lumbar Spine

- Head Balance

- Feet

We are going view the relationships between the first three places from the side of the body.

Figure 1: Balance Mascot.

You can check into these places and restore their alignment with each other as you prepare to play and as you perform.

The Sitting Bones

The first place are the sitting bones at the bottom of the torso.

Figure 2: Sitting bones.

These rounded and angled bones are the lowest bony place in your torso. Sitting on your sitting bones allows your legs to be free. The lowest place of each sitting bone is located in the middle of the body from front to back in the average person. Locate your sitting bones by sitting on the palms of your hands. Slowly tuck and untuck your tailbone to feel the sitting bones roll across your hands. Pause at the place where you feel the most pressure from the weight of the torso. You are now sitting on your sitting bones. Remove your hands to feel the connection between the sitting bones and chair.

Balance Check: As you sit on your sitting bones, how does your breathing feel? You may notice the air moving in and out more easily and perhaps breathing more deeply. Next explore arm movement. Wave your arms around and notice the quality of the arm movement. Compare the movement quality of breathing in arms to when you are sitting in front or behind the sitting bones, otherwise known as ‘out of balance.’ What changes? Finally, return to balance to enjoy the ease of movement that balance offers. Airplay your cello to notice how playing movement changes.

The Spine Ensemble

We are going to travel up from the sitting bones through the middle of the body. Between the sitting bones and the head is the long, curvy spine. The spine is comprised of bones and discs. It offers support and mobility to us. Its lowest point, the tailbone is at the level as the hip joint. If you are sitting, this is the place where your torso and leg make approximately a 90 angle. The top of the spine is located right below the holes of your ears, behind your earlobe. Locate the top and bottom of your spine by placing the finger of one hand where the leg bends in sitting and a finger from the other hand right behind your earlobe Between these two points are the ensemble of bones and discs that comprise the spine. Our next two places of balance involve two places in the spine.

Lumbar Spine

The next balance place in our map of sitting balance is the front of the lumbar spine (Figure 1). The lumbar spine is comprised of the bottom five vertebrae. These vertebrae curve into the middle of the body because of their size and shape. Locate the interior curve in yourself by placing your thumbs on the top top rim of your pelvis on the seam of your shirt and pointing in to the middle. Tuck and untuck your tailbone to feel how the lumbar spine moves when the sitting bones move. You will notice when you tuck your tailbone the lumbar spine moves back behind the sitting bones and when you untuck it, it moves forward of the sitting bones. Return to balance by restoring the connection of sitting bones to chair. When you do this, notice how your lumbar spine aligns directly above the sitting bones, in the middle.

Balance Check: Check in on the quality of arm movement and breathing. Your arms are free to move all around while the sitting bones and lumbar spine are aligned in balance. Compare the quality of movement to the same movements when out of balance.

We are building a clearer map of what balance or “home base” looks like on the inside. You can return to balanced alignment over and over as you breathe life into your music. Let’s continue to the next place…

Balance the Head

With the lumbar spine and sitting bones aligned in balance you might notice that your head is almost effortlessly floating above. To understand this better, let’s look at the anatomy.

Figure 3: Head Balance.

The top fo the spine meets the head in the middle of the body from front to back. In Body Mapping, this is the 1st place of balance, the A-O Joint. To get a better idea of where this is in your own body, place your thumbs right behind your earlobes pointing into the middle of the head. Use a mirror to check that the thumbs are parallel to the floor. Using your thumbs as an axis, nod your head gently as if saying ‘yes.’ You might even feel like a bobble head doll. Move one of your thumbs down to point into the balance place of the lumbar spine. Notice the alignment between these two places. How does the relationship change if you tuck or untuck your tailbone? How does the relationship change if your head moves forward in space? Return to balance by locating the balance place of sitting bones to chair and feel the lumbar curve and head almost magically align above.

Balance Check: Pretend you have your cello with you, bring it into the balance of your body. Next pretend to play. Notice how breathing and arm movement feels. Is this familiar or are you enjoying easier mobility? You can learn to play with the same ease that you are enjoying right now by understanding the design for balance.

Don’t forget your feet!!!

Feet play an important role in balance. They provide the stability for music-making mobility. Allow both feet to contact the ground equally. Walk your feet out to the sides and back. Balance in the torso doesn’t have to change when you do this. What happens to the organization of the torso if you wrap one foot around the leg of the chair? You probably notice a slight collapse on the same side. Two feet on the ground are an important part of balance. I like to think of “releasing the bottom of my feet into the ground.”

Let’s Play

You are ready to bring your cello into balance and play!

Step 1: Find balance, sitting bones, lumbar spine, head aligned, feet equally on the ground.

Step 2: Deliver your instrument back to you as you enjoy contact with the chair and floor. Don’t forget to breathe!

Step 3: Notice what it is like to sit in balance and have your cello contacting your body. Notice the points of contact it makes with your body, this may be different. What is it like to move your arms around, bow in hand, then deliver hand to the fingerboard and bow to the strings and play?

Step 4: Play! What is it like to play beginning from balance?

Step 5: Reset and play again.

Balance plays an integral role in musical expression. Think of it as home-base. You will leave it many times through a performance but knowing what it is like on the inside allows you to return again and again.

Your unique balance can be found by sensing the relationships we have discussed. (Figure 4) It is your point of departure as well as an organization to return to. Learning to sense balance in your body is similar to how you learned to discriminate pitch. You have already taken the first step by understanding the body’s design for balance and locating key places in your body. It takes time to integrate balance into your playing. You can make time away from your instrument practice time for balance by tuning into sitting bones, lumbar spine and head. Sitting in a concert is a great time to enjoy listening to the music and find balance. The more you practice, the more accessible it becomes. Balance allows you to learn music more quickly and avoid injury stemming from poor movement. At the beginning it is usually helpful to be aware of balance in warm-ups, tone and technique. As you uncover increased breadth of sound and expression you will be able to integrate this into more challenging passages. It is a beautiful and inspiring process! For more details check out any of the Body Mapping books or visit www.bodymap.com

Illuminating the anatomy behind playing movement is how Vanessa Mulvey guides musicians to transform their performances from good to great. The goal of her work is to cultivate healthy playing habits that unleash expression and resolve pain and injury. Following a Body Mapping workshop, Vanessa began exploring how the quality of movement translates into sound and expression. In her own playing, she uncovered increased musicality, reliable technique and relief from neck and shoulder discomfort. This inspired her to understand more about this relationship for both playing and teaching. A self-proclaimed movement geek, Vanessa takes advantage of opportunities away from the instrument to uncover fluidity and precision of movement, which has included leaping off the board to fly on the trapeze and a Spartan race. Vanessa is a faculty member of the New England Conservatory of Music and Longy School of Music of Bard College. Her teaching guides musicians to propel their artistry refining movement through Body Mapping and movement exploration. She coaches musicians one on one to address their individual needs, and presents specialty sessions at music schools, conferences and festivals. Venues include the Frost School of Music, the Boston University Tanglewood Institute, and the British Isles Music Festival. The core values of her teaching are comprised of practicing movement in the context of music-making and independently, embracing intention, and lifelong learning. Through these values she gains deeper insights to develop poise, confidence, consistency, and expression, and savor the path of mastery. A flutist and passionate proponent of new music, Vanessa performs in the Boston area. She completed Licensure with Andover Educators, the Body Mapping organization, in 2009, and now teaches the course ‘What Every Musician Needs to Know About the Body’ at both music schools and as guest artist. In 2017, Vanessa became President of Andover Educators. She is excited to foster this vibrant organization into its next chapter, raising awareness of strategies to reduce the rate of injury among musicians. Vanessa studied at the Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music (M.M.) and Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam (B.M.). This year she is looking forward to even more movement adventures, attaining Level 1 MovNat certification, and of course, more flying trapeze! See Vanessa’s schedule at: http://bodymap.org/main/?page_id=1313 or email her for more information vanessa.mulvey@necmusic.edu

Illuminating the anatomy behind playing movement is how Vanessa Mulvey guides musicians to transform their performances from good to great. The goal of her work is to cultivate healthy playing habits that unleash expression and resolve pain and injury. Following a Body Mapping workshop, Vanessa began exploring how the quality of movement translates into sound and expression. In her own playing, she uncovered increased musicality, reliable technique and relief from neck and shoulder discomfort. This inspired her to understand more about this relationship for both playing and teaching. A self-proclaimed movement geek, Vanessa takes advantage of opportunities away from the instrument to uncover fluidity and precision of movement, which has included leaping off the board to fly on the trapeze and a Spartan race. Vanessa is a faculty member of the New England Conservatory of Music and Longy School of Music of Bard College. Her teaching guides musicians to propel their artistry refining movement through Body Mapping and movement exploration. She coaches musicians one on one to address their individual needs, and presents specialty sessions at music schools, conferences and festivals. Venues include the Frost School of Music, the Boston University Tanglewood Institute, and the British Isles Music Festival. The core values of her teaching are comprised of practicing movement in the context of music-making and independently, embracing intention, and lifelong learning. Through these values she gains deeper insights to develop poise, confidence, consistency, and expression, and savor the path of mastery. A flutist and passionate proponent of new music, Vanessa performs in the Boston area. She completed Licensure with Andover Educators, the Body Mapping organization, in 2009, and now teaches the course ‘What Every Musician Needs to Know About the Body’ at both music schools and as guest artist. In 2017, Vanessa became President of Andover Educators. She is excited to foster this vibrant organization into its next chapter, raising awareness of strategies to reduce the rate of injury among musicians. Vanessa studied at the Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music (M.M.) and Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam (B.M.). This year she is looking forward to even more movement adventures, attaining Level 1 MovNat certification, and of course, more flying trapeze! See Vanessa’s schedule at: http://bodymap.org/main/?page_id=1313 or email her for more information vanessa.mulvey@necmusic.edu

Subjects: Playing Healthy