A New Look at Sight-Reading (Part 2)

Robert Battey

“I can play something ok if I have some time to practice it, but I can’t sight-read to save my life.” How many times have we heard this lament or some variant, particularly among adult amateurs? It does express a common deficiency. Sight-reading is a specialized skill, which must be acquired separately and in addition to one’s general technical work, so it’s quite common for a competent player to be a weak sight-reader.

The term “sight-reading” is a poor one since it’s both obvious (how else will you read music if not by sight?) and inaccurate (“sight-playing” is a little closer, though not by much). It’s been used to mean several different things, but the meaning we’re concerned with here, and the only context in which the skill level really matters, is when a musician plays through his/her part with an ensemble without having seen the music before. Those who can do this successfully are valued and in demand.

You can report to friends that you “sight-read” a movement from a Bach Suite at home, and you may indeed have done so flawlessly. But your sight-reading skill is only relevant when other players are depending on it. Good sight-readers are quickly distinguished from less-good ones when the music is going along at a predetermined pace and won’t pause for that extra split-second you need to find that new position.

The necessary skill set for true sight-reading is very different from the one most of us apply when we first try to play through a new piece we’ll be working on. There, we are thinking about finding optimal fingerings and bowings, and are analyzing the problems and trying out various solutions as we go. When we miss a note, we go back and fix it. When we come to a thorny passage, we slow down to be sure we are grasping everything. This is how we spend much of our initial practice time on a piece, but it is antithetical to good sight-reading.

And this is why there is often a disconnect between a player’s technical level and his/her sight-reading ability level. I have observed musicians of modest ability play “beyond themselves” in sight-reading situations, and others with virtuoso technique crash and burn when similarly challenged. The distinct skill-set for good sight-reading can be developed separately from one’s overall playing abilities, and indeed must be, if one aspires to become a competent ensemble musician.

When playing in a group, of any size, our overarching principle should be Primum non nocere (“First, do no harm”). If three, four, or nine people are sitting down to read through a piece, they do not want to stop. The cardinal sin for an individual player is to mess up to the point where the ensemble falls apart. And, just like the more serious sins in life, it is almost always avoidable if one follows a few basic tenets.

Here, the most basic tenet is: it’s all about the ensemble and enabling a successful read-through, even if not every detail is right. Some players (even high-level players) approach sight-reading like gladiators, and make it a point of pride to try and play every note regardless of steadiness. But that is neither music-making nor even decent sight-reading. The better approach, and one that can be cultivated from your very earliest attempts, is to always place the imperatives of the group ahead of one’s own wishes and needs.

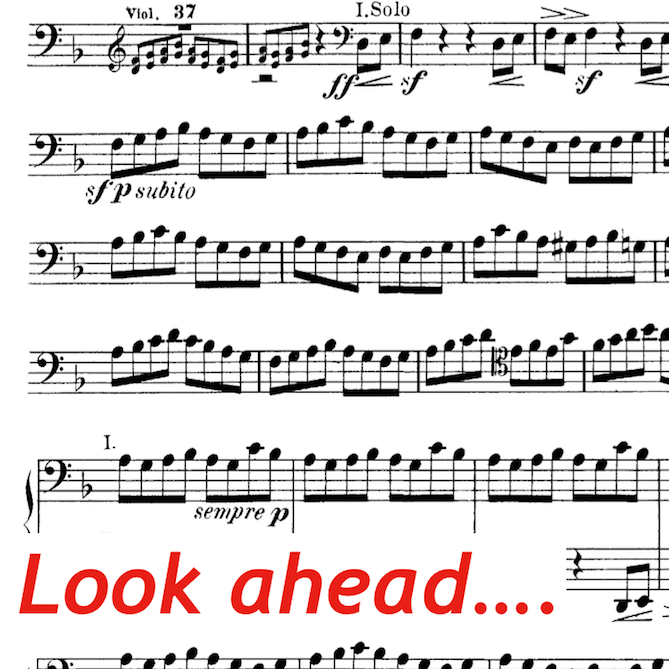

Everyone knows that good sight-reading requires the player to always scan ahead; to take in a new measure while still playing the current one. This “double vision,” like anything else, will improve over time with practice. But simply seeing what’s coming up is, of course, not enough. It’s how you process what you see, and how you then prioritize and execute, that counts.

In our next installment, we’ll discuss exactly how to do this.

Subjects: Practicing

Tags: ability, Battey, cello, cellobello, chamber music, ensemble, Observation, Practice, Rhythm, robert, sight-reading, success, Technique, virtuoso