Cello Concerto Overview: The Should Haves (Part I)

Janet Horvath

Reprinted with permission from Interlude.

Concert Favorites: Cello Concertos That You Should Learn

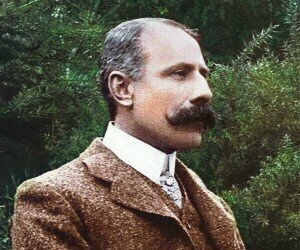

Wilhelm Fitzenhagen

My teacher János Starker used to say that cellist soloists have to be ready to play a greater number of concertos than our more brilliant sister, the violinist, who can play an entire season with four or perhaps five concerti under their fingers—think Brahms, Mendelsohn, Barber, and Sibelius; or Bruch, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, and Bartók. Likewise, audience members are thrilled to hear a pianist perform the masterworks of Rachmaninoff, Mendelssohn, Mozart, and either of the Prokofiev’s; or, Grieg, Schumann, Shostakovich, Bartók and either of the Ravels.

Cellists, though, have the disadvantage of fewer pieces written for their instrument and not all of them are considered the quality of the concertos named above. Some are neglected or obscure pieces. To complicate matters, there are fewer cello soloists on the roster of an orchestral season, although the days of cellists being “bad box-office” are thankfully behind us. All soloists must bow to the preferences of presenters or conductors.

A closer look into the repertoire reveals, in addition to the concertos which might immediately come to mind, a large number of works that might enhance our offerings and be appealing to a presenter. We will begin with the concertos I think a cellist should have in their repertoire. Next, we will move on to works, which I hope you agree, deserve to be played and heard, concertos you could have in your repertory, and then to works that have recently been written for our instrument, a selection of which you ought to have in your repertoire.

Cello Concerto Should Haves:

Antonín Dvořák: Cello Concerto in B minor (Kian Soltani)

Antonin Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor, Op.104, perhaps the best-known and most beloved cello solo, is lush, romantic, and technically challenging. Dvořák was unsure of the soloistic capabilities of the cello, and he repeatedly resisted the pleas of his friend cellist Hanuš Wilhan to write a concerto for him, but after hearing Victor Herbert perform his second cello concerto, Dvořák decided perhaps the cello was suited after all. The concerto begins with a long and grandiose introduction from the orchestra. The cello enters “Quasi Improvisando” with a declamatory statement, then the soloist is in turn bold, spirited, and expressive while executing difficult double stops, chords, and fast passage-work. A poetic adagio follows. One of my favorite moments in this movement is a cadenza accompanied by the flutes, where the cello plays not only long beautiful lines with the bow, but also double notes and left-hand plucking or pizzicatos, an uncommon technical challenge. The finale, a rondo, is dramatic, with pulsating lower strings featuring the full power of the brass section. For me the climax is a gorgeous duo for the cello soloist and the concertmaster. Note the young Persian-Austrian cellist Kian Soltani’s performance. The piece ends, as Dvořák put it, “stormily.” After Brahms heard the cellist Hugo Becker perform the concerto in 1897, Brahms said, “If I had known it was possible to compose such a concerto for the cello, I would have tried it myself.” If only he had! The challenge of the Dvořák concerto is having the stamina to perform this long and larger-than-life work with a powerful, opulent tone to rise above the large orchestration.

Edward Elgar: Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85 (Jacqueline du Pre & Daniel Barenboim)

Similarly, Edward Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E Minor Op. 85, another masterwork, requires not only a full, rich sound but emotional depth to transport the listener into Elgar’s melancholy world during his waning years.

Edward Elgar

Cellists Carl Fuchs of the Brodsky Quartet, and Paul Grümmer, had requested a concerto from Elgar at the turn of the 19th century, but Elgar didn’t write his concerto until 1919. In four movements, the opening is also free and dramatic like the Dvořák Concerto. The extremely virtuosic second movement, similar to a moto perpetuo, requires an elfin spiccato or off the string bow stroke, as well as rapid finger-work throughout. It is followed by a breathtaking and tender slow movement, and the finale ends full of pathos. The four movements merge into one another in rhapsodic fashion, rather than in strictly individual and contrasting movements, and the themes return to embody Elgar’s deep anguish, and disillusionment in the aftermath of World War I. The concerto requires not only technical mastery but also a palette of sound summoning all that a cello can express to convey the profundity of this work. Jacqueline Du Pré’s landmark recording with Sir John Barbirolli (album title: Jacqueline Du Pré – Favourite Cello Concertos) is still regarded as the classic interpretation of the work. Here, a whole ensemble of child prodigies play the concerto.

William Walton: Cello Concerto

William Walton

William Walton’s Concerto written in 1956 was commissioned by and written for Gregor Piatigorsky. A very short introduction, a matter of a few bars, and the cello enters with a lyrical impressionistic sounding melody, punctuated by the flutes, celeste, harp and vibraphone, which rarely appear in cello concerti. The first movement explores the sonorous range from low to high followed by a spiccato fast movement, not sylphlike as in the Elgar, but heavier and urgent. This work is also introspective at times but it explores the gamut of expressive capacities of the cello from romantic to brilliant, and includes several dazzling solo cadenzas. The orchestral accompaniment is relatively sparse therefore conducive to making way for the cello solo to soar bewitchingly. It is a major work, which I believe is receiving more of its due today with the release of several new recordings.

Joseph Haydn: Cello Concerto in D (Mischa Maisky)

Joseph Haydn’s Cello Concerto in D is considered a classic. It’s lyricism, elegance, and shimmering lightness, charms audiences. Not for the faint-hearted cellist, it is full of scale passages running into the topmost range, which requires great deftness and fluency in both the bow arm and left hand. There is no hiding in this piece—purity of sound, intonation, and rhythm are a requirement. It was composed in 1783 for Antonin Kraft, a cellist of Prince Esterházy’s orchestra for whom Haydn worked from 1762-1790 as Kapellmeister and composer, and is a work of great beauty and flair. Play this well and you’ll have the admiration of cellists, as well as conductors and audiences.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Variations on a Rococo Theme (Jian Wang)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations is the closest the composer came to writing a full concerto for the cello. A great admirer of Mozart, Tchaikovsky wrote the piece with a reduced orchestration and in the late 18th century Rococo style with cellist Wilhelm Fitzenhagen’s input. Don’t let its short and sweet character fool you. Approximately twenty minutes, the theme and variations are written in the highest registers and like Haydn, require not only exemplary technique and purity of approach, but also quick changes in character and mood. There are two plaintive slow variations, variations with spectacular trills and double notes, two cadenzas, and a ferocious and difficult last variation. Since it immediately displays a variety of technical challenges, I have played this piece for auditions. Rococo Variations is a romantic and bravura showpiece while still maintaining the transparency and charm of an earlier period.

There are six more concerti of should haves. Stay tuned!

By Janet Horvath. Republished with permission from Interlude, Hong Kong.

Subjects: Repertoire