A Much Maligned Cellist: The True Story of Felix Salmond and the Elgar Cello Concerto (Part 1)

Tully Potter

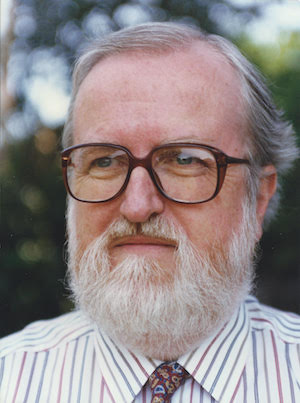

Blog photos courtesy of the Tully Potter Collection.

This article first appeared in the Elgar Society Journal.

Tully Potter tries to lay a myth to rest.

Sometimes a myth becomes so firmly entrenched in the public consciousness that the true facts are completely obscured. So it has been with that archetypal English cellist Felix Salmond, whose career is always woefully misrepresented. In his adopted country, the United States, he is remembered for teaching at Juilliard and Curtis and nurturing most of the prominent 1930s and post-war American cellists. In Britain he is indelibly linked with the premiere of Elgar’s E minor Concerto, an event now encrusted with fables.

Felix Adrian Norman Salmond was born in London on 19 November 1888, to musical parents: his father Norman was a professional bass-baritone who sang Richard Coeur-de-Lion in the original cast of Sullivan’s Ivanhoe and had a busy career in light opera, also singing at many of the major festivals; and his mother Adelaide, who always appeared as Mme Norman Salmond, was a remarkable pianist. Born in New York in 1855, she was the daughter of the Italian opera conductor Mariano Manzocchi, who taught Adelina Patti. Coming to London aged 15, she so impressed Sir Julius Benedict that he gave her a letter of introduction to Franz Liszt in Weimar; but her mother sent her to Brussels, where she studied with Auguste Dupont, and to Frankfurt where her teacher was James Kwast. She knew all the great pianists and had lessons for a time from Clara Schumann. After her husband’s death, she concentrated on her son’s career. As a boy Felix played piano and violin, and took up the cello only at 12, taught by W.E. Whitehouse. At the Royal Academy of Music in 1903 he was highly commended but missed a scholarship. In 1904 he won the All-England Open Scholarship and in 1905 entered the Royal College of Music, where Whitehouse was a professor, remaining until 1909. From 1907 he took lessons in Brussels with Edouard Jacobs during the holidays. At the RCM his chamber music tutor was Frank Bridge, who became a close friend.

On 8 December 1908 Felix appeared at the Bechstein (now Wigmore) Hall, taking part in Brahms’s G minor Piano Quartet with his mother, Maurice Sons and Frank Bridge, and premiering Bridge’s Fantasy Trio. The Times commented that “though nominally making his début to a London audience, he was clearly not unknown to the majority of the audience, who greeted his appearance with tumultuous applause; this must have been disconcerting, but for all that Mr. Salmond played a Boccherini Sonata with great finish” (The Times, 10 December 1908). On 28 October 1909 he made his London recital début at the same hall, playing Beethoven’s A Major Sonata, Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations, Popper’s Tarantella, Fauré’s Élégie and Bridge’s Serenade with his mother, who contributed some solos. The Times noted “the beauty of his tone and the smoothness of his phrasing” (The Times, 29 October 1909). It was the first of a number of appearances by the Salmond Duo: Sir Henry Wood thought them “an excellent and artistic combination” (Wood, pp. 381-2). On 11 June Felix took part in the premiere of Bridge’s Sextet, with Ernest Tomlinson and the English String Quartet, including the composer. In 1912, while playing in the orchestra at Daly’s Theatre, Leicester Square, where English versions of Viennese operettas were produced, he met and married his first wife Lillian—his mother was far from happy at acquiring a chorus girl as a daughter-in-law and the resulting friction did not help the marriage to flourish. In 1912-14 he was a regular at the legendary late-night chamber music sessions hosted by Paul and Muriel Draper at 19 Edith Grove, Chelsea, recalled in the autobiographies of Artur Rubinstein, Eugène Goossens III and Lionel Tertis, and in Muriel Draper’s own charming memoir (Draper). On 12 February 1914 Salmond played Saint-Saëns’s A minor Concerto at Queen’s Hall and on 23 September, by which time Britain was at war, he made his Proms début with Eugen d’Albert’s Concerto: the conductor, as for all his Proms, was Sir Henry Wood. He rapidly began to shine in such concertos as the Haydn D Major and Dvořák, collaborating with many celebrated musicians. Unfit for active service in the Great War, he worked as a clerk in the Grenadier Guards’ headquarters, with the rank of private, and joined in the regiment’s public concerts with Guards musicians such as Albert Sammons and the Australian pianist William Murdoch. On 13 July 1917 he and Murdoch introduced Bridge’s D minor Sonata at the Wigmore Hall. Among other commitments he had a regular trio with Rhoda Backhouse and Harold Samuel.

Elgar’s chamber music

On 26 April 1919, at Frank Schuster’s Westminster home, Salmond took part in private performances of Elgar’s new Quartet and Quintet, with Albert Sammons, W.H. Reed, Raymond Jeremy and William Murdoch. The generous Schuster footed the bill for this all-star ensemble and invited members of the musical press to hear the two works. Rosa Burley recalled that there were other trial performances in the big music room at Severn House: “On 7 March, when I heard them, the party included Bernard Shaw, for whom in later years Edward had conceived a great admiration” (Burley & Carruthers: 201). On 21 May 1919 the same players were involved in the first public performances, at the Wigmore Hall, when the Violin Sonata, which had already been premiered, was heard as well. (These were just two of the occasions when the eminent quintet performed the Elgar chamber works: W.W. Cobbett recalled “a wonderful performance” at the Salmond home—see “Sir Edward Elgar: Chamber Compositions,” a letter published in The Times, on 2 March 1934).

Salmond was the natural choice for expert adviser on the Cello Concerto in E minor which Elgar now began writing. Soon Salmond was being consulted on various matters concerning the composition: on 5 June, and again five days later, he was at Severn House to try out what Elgar had written. It is possible that Elgar had not firmly settled the order of the two inner movements, as Lady Elgar wrote in her diary on 22 June that he was “finally revising the beautiful 3rd movement of Cello Concerto, “Diddle, diddle diddle.’” Elgar, an excellent violinist, hardly needed advice from Salmond on string technique, but he may have wanted assurance that what he had written was playable. One can imagine the Scherzo came up in the discussions—generations of cellists have struggled with the saltato bowing in it, and some famous names have fallen short. Salmond had a very serviceable technique, and with his huge hands could make enormous stretches, but he must have been tested. To his credit, he evidently did not persuade Elgar to compromise on the virtuoso demands of the Concerto. On 31 July he arrived at the composer’s Sussex retreat Brinkwells for a short stay, so that he and Elgar could work intensively on it. After tea they went through the Concerto, and after dinner they returned to it. From Lady Elgar’s diary we learn that following breakfast the next day, a further run-through took place, and that “Mr Felix” was “such a delightful visitor.” Elgar took Salmond fishing, with no success; after dinner more work was done on the Concerto; and Elgar then offered Salmond the premiere. The cellist was so thrilled that he hardly slept that night. More work was accomplished on the following morning, and Salmond left after lunch. Back home at 7 Northwick Terrace, N.W. 8, he wrote to Lady Elgar:

I must write a short note to tell you what a real pleasure it has been to me to have stayed with you & Sir Edward, & I want also to thank you for your more than kind hospitality. The three days were altogether memorable in many ways, & my stay with you both will always remain one of my most delightful recollections. Will you tell Sir Edward that I played the Concerto through this morning by heart!!

What a thrilling & proud evening its production will be for me!!

It is not possible for me to express how very deeply I appreciate the great honour Sir Edward paid me by entrusting the debût of his beautiful work to a comparatively unknown artist. May I prove myself entirely worthy of his great faith in my powers!

It is a chance that but rarely falls to a young artist, and I intend to try my hardest to take the golden opportunity with both hands!

If hard work can make it a success, Sir Edward can rely on my industry – Once again, warmest thanks for your many kindnesses.

Greetings to you all –

Believe me, very sincerely yours

Felix Salmond

P.S. My calligraphy this morning is appalling, & practising is the reason! Cello playing & writing do not mix!!

(Letter dated 3 August 1919)

By 8 August the manuscript score was ready and Lady Elgar took the new Op. 85 in person to Fittleworth post office to send it to Novellos with the final proofs of the Quintet. On 18 September Salmond played the Lalo Concerto at the Proms and on 2 October the Saint-Saëns A minor, incidentally refreshing his memory of the acoustic of Queen’s Hall, where the Elgar Concerto was to be premièred on 27 October. Most of the programme–Borodin’s Second Symphony, Wagner’s Forest Murmurs and Scriabin’s Poem of Ecstasy—would be directed by the orchestra’s new conductor, Albert Coates, and following the Borodin the Cello Concerto would be conducted by the composer. Sir Edward was accompanied by Alice and their daughter Carice for the first rehearsal at Mortimer Hall and in her diary Lady Elgar (writing of herself as ‘A’) gave a vivid description of the humiliation meted out to Britain’s greatest living composer by the arrogant Coates:

October 26. … horrid place – the new work, Cello Concerto, never seen by Orchestra – Rehearsal supposed to be at 11.30. After 12.30 – A. absolutely furious – E. extraordinarily calm – Poor Felix Salmond in a state of suspense and nerves – Wretched hurried rehearsal – An insult to E. from that brutal, selfish, ill-mannered bounder A. Coates.

October 27. E. and A. and C. to Queen’s Hall for rehearsal at 12.30 or rather before – absolutely inadequate at that – That brute, Coates went on rehearsing ‘Waldweben’. Sec. [of the LSO] remonstrated, no use. At last just before one, he stopped & the men like Angels stayed till 1.30 [half an hour into overtime]. A. wanted E. to withdraw, but he did not for Felix S.’s sake – Indifferent performance of course in consequence. E. had a tremendous reception & ovation.

Elgar was beginning to go out of fashion and the hall was not full, but in the audience were a fair number of critics and some of the staff of the Gramophone Company, who issued Elgar’s recordings on the “His Master’s Voice” label. As Lady Elgar indicated, those present were all, or almost all, keen Elgarians and appreciated the beauties of the Concerto, even though it was not the sort of upbeat effusion that many English people might have wanted, less than a year after the trauma of the Great War.

The story continues in Part 2.

Works Cited

Burley, Rosa and Frank C. Carruthers. Edward Elgar: The Record of a Friendship. Barrie & Jenkins: London, 1972.

Draper, Muriel. Music at Midnight. Harper & Brothers Publishers: New York & London, 1929.

Wood, Henry J. My Life of Music. Victor Gollancz Ltd: London, 1938.

TULLY POTTER was born in Edinburgh in 1942 but spent his formative years in South Africa. He is interested in performance practice as revealed in historic recordings and has written for many international musical journals, notably The Strad. For 11 years he edited the quarterly magazine Classic Record Collector. His two-volume biography of Adolf Busch was published in 2010 and he is preparing a book on the great quartet ensembles.

TULLY POTTER was born in Edinburgh in 1942 but spent his formative years in South Africa. He is interested in performance practice as revealed in historic recordings and has written for many international musical journals, notably The Strad. For 11 years he edited the quarterly magazine Classic Record Collector. His two-volume biography of Adolf Busch was published in 2010 and he is preparing a book on the great quartet ensembles.

Subjects: Historical, Repertoire

Tags: cello concerto, composers, Elgar, Felix Salmond, premiere