Reflections on the 17 Beethoven String Quartets: Some Interpretive Considerations (Part 4 of 5)

Paul Katz

Some Interpretive Considerations

By Paul Katz

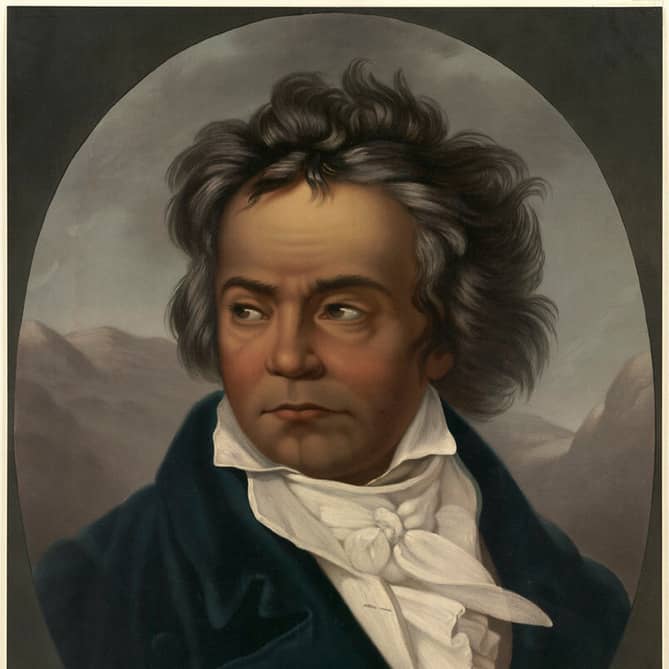

It’s 2020, we are celebrating Beethoven’s 250th birthday, and I decided it is the perfect time to revisit the album notes I wrote 45 years ago for the Cleveland Quartet’s recorded Beethoven Quartet Cycle on RCA Victor. The 17 quartets of Beethoven were the core of our 26-year career as we immersed ourselves in research, score study, years of exhilarating rehearsals, two recorded cycles, 30 complete cycles in the major capitals of the world, and literally thousands of Beethoven quartet performances. Musicians generally agree that there is no other music as rewarding or profound in all of western music. These masterpieces have challenged me as a musician and enriched my life – what a privileged existence!

Formed in 1969, the CQ knew only 2 Beethoven quartets for the 1970 Beethoven bi-centennial year, but we joked that we would be ready for a cycle in 2020! Though it’s 50 years later and the Cleveland Quartet is no longer active, I could not let this special year go by without participating in some way, and so I returned to my notes written between 1975-1980, and reduced and edited them for this series of CelloBello blogs. The original project was voluminous – 3 boxed sets of LP vinyl, with written liner notes discussing each individual quartet. I have taken about 20% of that original project and rewrote it for CelloBello in five-parts: The Early, Middle, Late Quartets, the Metronome Markings, and Interpretive Considerations.

Some Interpretive Considerations

No composer has expressed Man’s deepest emotional states as profoundly as Beethoven. There is a heartfelt depth to the musical experience, an enlightened level of consciousness, a sincerity and nobleness of concept that enriches and inspires. “Those who understand (my music) must be freed by it from all the miseries that others drag about with themselves,” Beethoven is reported to have said. Whether or not he actually uttered these words is ultimately unimportant, for generations have found in his music the noblest and purest expression of universally shared human values such as Love, Joy, Freedom, and Peace. There is despair and anger, even rage, but never hate, not a cynical or bitter note. Pain and suffering (which he knew better than most are beautifully expressed to us as a necessary part of the synthesis of life.

The interpretive process can be the most creative, fascinating, rewarding part of a musician’s life, but it is an extremely complex unfolding that artists continually contemplate and that evolve over time. How do we best honor our responsibility to the composer? Are the composer’s markings, and the surrounding historical and theoretical facts illuminating? Or are they puzzling, in conflict with our instincts?

It is interesting to consider the various interpretive aims and motivations that affect artists and their musical decisions, and musicians do not always agree. Some use a work simply as a vehicle for expressing their own personalities; others believe they should submerge their own individuality, let the music speak for itself by only reproducing the composer’s printed notations; others attempt to recreate a performance the composer himself would have wanted to hear. There is at least partial truth to each of these approaches – careful attention to the composer’s indications, a learned theoretical and historical perspective, and the individual imagination of the performer, all contribute to a successful performance. It is the integration, the synthesis of all these elements that leads to valid, communicative interpretation.

The great pianist, Alfred Brendel, in “Musical Thoughts and Afterthoughts,” says it eloquently:

Music cannot “speak for itself: the notion that an interpreter can switch off his personal feelings and instead receive those of the composer “from above” belongs to the realm of fable. What the composer actually meant… can only be unraveled with the help of one’s own engaged emotions, one’s own senses, one’s own intellect, one’s own refined ears. It is our moral duty to make music as visionary, moving, mysterious… as we are able to: but this raises the question, ‘What will move, shatter, edify or amuse our contemporaries?’ To… strike the noblest, the most elemental resonance in modem man—it is this task that raises the Urtext interpreter above the status of museum curator.

In other words, the concern is not what would have exactly pleased Beethoven in the early 1800s, but rather, how to execute his printed intentions in a way that communicates the emotional essence of the work today. Our high-speed 21st century world of jets, mass media, large halls, and two hundred years of music written since Beethoven, must inevitably result in performance differences. Times, tastes and performance practices change but the human emotions expressed remain eternal, and it is the performer’s duty to communicate these to the listener of his time.

Of course, even a 21st-century interpretation should be informed by certain stylistic considerations and performing aesthetics of the composer’s time, as some of these elements are intrinsic to the work itself. We know that Beethoven the performer made tempo changes between first and second themes, so although that tends to be frowned upon in our time, I believe it can be helpful and freeing information for today’s musician. Grace notes in the early 19th century were generally still played on the beat and trills usually started from the upper note, but these “rules” are more relevant to the Op. 18 quartets – performance practices were changing in the early 1800’s and they apply less to the middle and late periods.

As we musicians begin to learn a work, instinctive feelings of mood and character stimulate countless early decisions of tempo, articulation, phrase-shaping, timing, etc. Through score study, rehearsals, and our individual reflective processes, these decisions evolve, change, refine over time, and eventually merge into an “interpretation”. Personally, I look at a composer’s notations as clues to the character and emotion they intended. For example, there are many ways to execute an accent mark: Is it scary, painful or a heart throb (in other words, what does that accent mark mean)? Should I use bow speed or faster vibrato? Should I attack the string with a bite, or should it be a more cushioned stress? In other words, what was the composer trying to say?

Fidelity to the text is important, in some ways sacred, yet the thinking musician should never blindly accept what is on the page. In the case of the Beethoven Op. 18 quartets, many of the wishes of this unique genius will never be known. There are no surviving manuscripts, and we know that Beethoven was unhappy with their publication:

Herr Mollo has once again published my quartets full of mistakes and errata on a large and a small scale. They team in it as fish do in water, i.e., ad infinitum … my skin has been greatly cut and ripped over these fine editions of my quartets.

(Letter to Hoffmeister. April 1802)

Succeeding early editions, unfortunately, show no major revisions, and so we must conclude that not even the recent scholarly editions of the Op. 18s can know many of the composer’s wishes. We do have the middle and late quartets in Beethoven’s own hand, but because of the messy and sometimes indecipherable condition of these manuscripts, there are still questions of articulations, dynamics, and in some cases, even the proper pitch of a note is unclear. A careless attitude on Beethoven’s part should not be inferred from this lack of neatness, for he expressed often and in no uncertain terms the wish that his markings be copied and executed exactly. What at first might appear to be sloppiness can better be understood as the process of composing, working out problems on paper, adding a new idea or discarding another, often in a rather emotional state: “[I am] excited by moods, which are translated by the poet into words, by me into tones that sound and roar and storm about me until I have set them down in notes.”

Comparison of all existing source material by modern day scholars has provided enormous insight for today’s performer. And scholarly work continues – my colleague Nicholas Kitchen of the Borromeo Quartet has recently made some fascinating observations on previously unnoticed super-meticulous dynamic markings. But although we have many useful sources (sketchbooks, the manuscripts of the middle and late quartets, early printed editions and even Beethoven correspondence regarding these works), ambiguities and conflicts between them will never be completely resolved. Many of Beethoven’s wishes can never be known, and subjective decisions and educated guesses will always be needed.

An interpretation, then, is the process of merging one’s instinct and intellect -at various moments they may interact compatibly while at other times they may be in conflict. The serious musician goes through a process to resolve these differences so that all considerations eventually become a compelling whole. It’s a journey each player, each ensemble, takes in its own way, giving life and contemporary meaning to music written over 200 years ago and ensuring that these masterpieces remain alive and relevant for future generations.

Subjects: Chamber Music, Repertoire