The Injured Cellist

Martha Baldwin

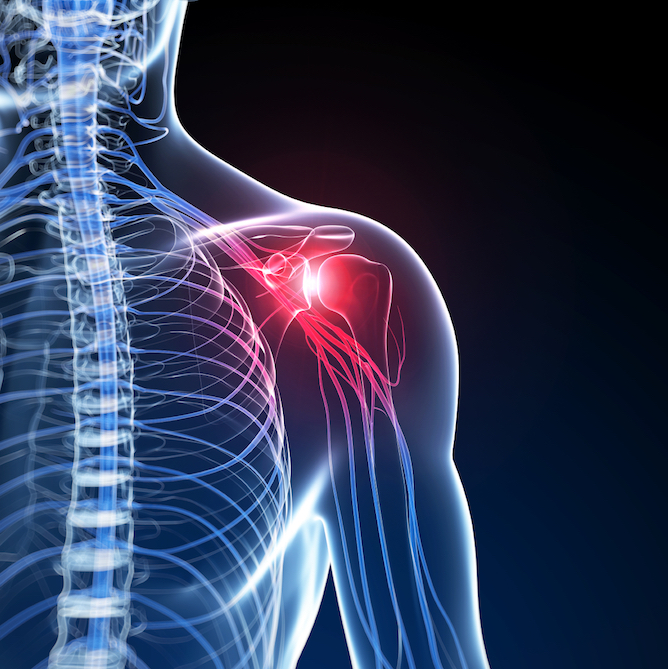

Like most of us cellists out there I can barely remember my life before my cello was a daily part of it. Sometimes it is the happiest, most ultimately satisfying part of my day, sometimes the most frustrating. Being a cellist is my life’s work, one that defines me utterly. While other aspects of life are undoubtedly more important (friends, family, health, happiness), what we do is a big part of making up who we are. Not doing it anymore is an exercise in redefining who you are. For nearly 18 months during the 2008/2009 and 2009/2010 seasons I couldn’t play the cello. A pretty common rotator cuff injury resulted in surgery, rehab, and a long period of complications and set backs. I won’t go into all the medical details, partly because it makes for pretty dull reading, and partly because my medical knowledge is such that I’d probably get a lot of things wrong and start sounding like an idiot. Suffice to say, when your doctor asks “Do you have any other marketable skills that you could use for employment the rest of your life?” you know it’s time to… well, I panicked. And cried. And had long “what now?!” talks over beers at our neighborhood bar with my wonderfully patient (non musician) husband. I learned a lot during those 18 months and the time that has passed since I was able to return to work in September 2010. I learned from the things I did wrong, the things I got right, and I learned a lot from the remarkable people—both medical and otherwise—I spent a large part of those days with.

Pain is important.

Learn to listen to your body and trust what you know about yourself. Learning what pain is serious and what will go away with a little time, rest, and sometimes just a glass of wine and a hot bath is crucial. We all have lots of the later—especially those of us cellists who do a lot of traveling. When we’re on tour with the orchestra our cellos travel in trunks separately from us. Often life goes like this:

3 days of no access to your cello, 2 flights, 4 bus rides, weird hotel beds, too much bratwurst, then you play a Bruckner Symphony. Repeat. For 3 weeks. Most of those pains go away once I get home.

When the pain gets so bad and your arm gets so weak you can no longer actually press down the strings with your left hand, you should have stopped playing some time ago.

Just say NO.

When a doctor says “It’ll be ok—after all, you JUST play the cello” it’s probably time to find a different doctor. My surgeon was fantastic but I did see a doc a year earlier who said this. Letting him convince me that continuing to play with a torn rotator cuff was ok was not my best moment. It’s important to stop playing and recover when an injury warrants it. Yes, it’s disappointing to have to cancel performances but it’s better to cancel a few weeks worth and recover quickly than be forced to stop for 2 years.

Get treated like an athlete.

I really turned the corner after working with a physical therapist who works with Major League baseball players on their shoulders. I did hours of rehab every day with him. Hours. It’s why I’m back playing with my orchestra and not back at school starting a new career. He adapted their program for my injury and my body – that made all the difference.

Buddy up.

I was especially lucky. When I was injured one of my colleagues and a good friend in the orchestra also had a shoulder injury and was unable to play. His was a different injury than mine but we were out of work at the same time doing a lot of the same treatments. I can’t tell you what a difference it makes having someone who truly understands both the emotional and medical side of things to talk to. We were both facing the possibility of never playing again, both dealing with shoulders, and were able to share resources (he recommended my physical therapist). You may not be quite as lucky as me but there’s almost always another cellist out there who has had the same injury/ surgery/ treatment and can really help. Having someone with whom to share not just the hard stuff but who understands how exciting it is to manage a full 5 seconds with the body blade (and actually knows what that odd piece of PT equipment even is) is more helpful than you can imagine.

Do what you need to do.

While I was injured a lot of friends would ask “why weren’t you at the concert on Friday?” “Why don’t you come to rehearsals and say hi?” Perfectly reasonable but while I was injured I just couldn’t do it. I rarely even listened to classical music. Attending concerts was far from relaxing—because I didn’t know if I’d ever get back on stage they sent my mind reeling into dark and angry places. Stopping by to “say hi” was hard. Putting on a happy façade when talking with colleagues running off to rehearsals while you’re running off to yet another MRI is exhausting and depressing. So I didn’t go. I cooked, I read, I taught, I listened to non-classical music, went out with close friends, travelled, and spent a lot of time in the gym and at the Cleveland Clinic.

Stick to a maintenance program.

Now that I’m back at work I find I have to keep up with my “program” in order to stay pain-free. I know when I’ve slacked off for a few weeks because little things will bug me. In my case I have to do my therapy routine 3-4 days a week. When we travel I have to bring some equipment with me and that’s ok. Also I get a massage every other week. It sounds a bit extravagant but, for me, it makes sure that little muscle knots or pulls don’t turn into anything problematic. Now, I’m not talking about some spa-day, lavender scented, candle-lit massage. I’m talking about one of the Cleveland Cavaliers’ massage therapists coming to my house and really working on my body. I would imagine its strange for her to go from working on Shaq’s arms to mine! Luckily Kate does house calls, lives in my neighborhood, and really keeps everything in check. Also, it’s tax-deductible.

Finally, I would say one thing about major injuries—they suck. I refuse to give you some “the journey taught me so much that I’m grateful for it” line. It sucked. It was painful and scary and stressful and more emotionally draining than I would have ever expected. BUT, you get through it and play again and the months of struggle quickly fade into a memory. Relearning to play wasn’t hard—it took far less time than I thought it would. The body remembers and with a little patience, it’s really not hard to regain your skills. I have no desire to ever go through that again, but if I had to I could. It was worth it.

Subjects: Playing Healthy

Tags: Baldwin, cello, cellobello, happiness, health, Injuries, maintenance, Martha, musicians, pain, performances, relaxing, Rest, taking time off, Travel